Resilience through Lean at Alliance MIM

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA - Alliance MIM navigates market crises leveraging Lean Thinking, emphasizing flow, maintenance, deep process knowledge, and visible learning to stay competitive in a complex, high-precision manufacturing environment.

Words: Catherine Chabiron

I am excited to return to Alliance MIM today and see CEO Jean Claude Bihr again (although ‘CEO’ only partially covers the breadth of his experience… he’s also an entrepreneur, a scientist, and, perhaps most importantly, a lean thinker).

The company has been able to maintain its position in the niche Metal Injection Moulding (that’s what MIM stands for) market despite many crises, largely thanks to their lean approach. Back in 2008, Jean Claude steered the organization through a time of great change, as the world transitioned to smartphones and the market of metal parts used in telephone keypads started to dry up. On my visit today, I am learning how the company is tackling yet another difficult time using Lean Thinking.

THE COMPLEX EQUATION OF ALLIANCE MIM

Alliance MIM produces high-precision metal parts through powder injection, moulding, de-binding, sintering, and machining. While the MIM process reduces material loss compared to machining from a metal bar, it struggles to compete with the large-scale conventional machining operations in China. In fact, Jean Claude tells me, Alliance MIM’s customers often admit that their products are the best but that they are “too expensive compared to China.” Consequently, the business focuses on small runs of complex parts with limited margins. Making things more complicated still is the saturated local job market, which impacts Alliance MIM with high levels of absenteeism and turnover, with the underlying risk of losing key skills. Lastly, orders from their aerospace, watchmaking, and medical customers have dwindled, leading to a significant sales drop in 2024.

Because of this, Jean Claude had to suspend temporary contracts, cut a few night shifts, and stop recruiting. He preserved cash flow by halting investment, idling unneeded machines and maintaining others, making more repairs (sharpening milling cutters four times before replacing), and eliminating non-essential expenses. What he never sacrificed, however, was maintenance.

The outlook for the next five years is complicated. Alliance MIM sells high complexity/low volume parts. Rising gold prices are impacting watchmakers' demand. The current war on tariffs is creating uncertainty. Over the past 30 years, as industry moved out to Asia, Jean Claude has witnessed and suffered from a gradual decline in industrial knowledge in the West, both among machine suppliers and buyers. Indeed, according to the Center for Global Development, China will likely capture 43% of global industry jobs by 2050.

The last element of the equation? Alliance MIM needs to recruit and retain engineers who are passionate about its product and machines, with larger companies possibly offering less interesting field jobs but better career prospects and benefits.

Anyone else would have given up, but not Jean Claude. “If your internal reaction speed is slower than external change, boy, you're in trouble,” he says.

LEAN AS A SOLUTION

Jean Claude and I are visiting the workshop. “The only way to survive is to produce small, fluid batches on well-maintained machines,” he tells me. Alliance MIM’s gemba demonstrates this with a pull flow, from shipping to injection, regular SMED, and reliable machinery. “Mould changes only take a few minutes,” Jean Claude explains, “but stabilizing the first parts still takes time.”

He then shows me a U-shaped cell, from injection to machining and inspection. “I did a bit of gemba observation recently,” he tells me (Jean Claude is very familiar with the Ohno circle), “and I saw a lot of useless motion. My job, as a boss, is to reduce costs and work on waste.” He shows me how the cell was worked over to bring the machines closer and reduce motion.

Jean Claude points out other examples of improving the flow during the gemba walk, but my point of interest today is Alliance MIM’s manufacturing engineering, specifically the machines and their transformation processes. Jean Claude often expresses concern about the loss of industrial knowledge in France, a problem I know he has worked hard to counter in his plant, and I believe we could all learn from his experience.

KNOWING YOUR MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT INTIMATELY

There are 250+ pieces of equipment in the Alliance MIM factory, including sintering furnaces, injection moulding machines, milling machines, lathes, measuring instruments. The MIM sector is both machine- and people-intensive, but with a very high material yield that explains its competitiveness.

Jean Claude says: “The problem is that machine manufacturers now subcontract installation and repairs and are consequently very far from the daily issues we experience. Look at this engraving machine, there’s only one after-sales technician for it in the whole of Europe, which causes delays in diagnosis and repair. This issue is critical in the aerospace industry, where certified machines are required. So, as a precaution, we overstock those machines.”

Jean Claude has plenty more stories about poor industrial reflexes. In one case, a customer commissioned a laboratory to inspect a sample part - and the lab delivered unrealistic conclusions without a second thought. As a result, the entire batch had to be redone. “They made a mistake analyzing a single part, concluded the whole batch was defective, and never bothered to double-check,” he says.

“Look at those thermocouples,” he points out. (If you are, as I was, unfamiliar with these, a thermocouple measures temperature using two metal wires joined at both ends. One junction measures the temperature, while the other is kept at a constant lower temperature. The resulting temperature difference creates a measurable electromotive force that can be translated into a temperature reading.) “Our US supplier installed the wrong diameter. We found it while working on the performance. Switching to the correct diameter quadrupled their service life.”

Another supplier had informed them that the thermocouples could not be calibrated above 1,200°C while the range of precision needed by Alliance MIM begins at 1,200°C. The supplier suggested extrapolating from the data calibrated at that temperature. “This is scientifically absurd,” Jean Claude tells me angrily, “as you can only extrapolate between two calibrated measurements, not from a single one.” Alliance MIM turned to a UK supplier who had more expertise in the thermocouple business.

ACCEPT AND UNDERSTAND DEVIATIONS

“I can’t see any visual maintenance plan out there in your workshop,” I tell Jean Claude at one point during my visit.

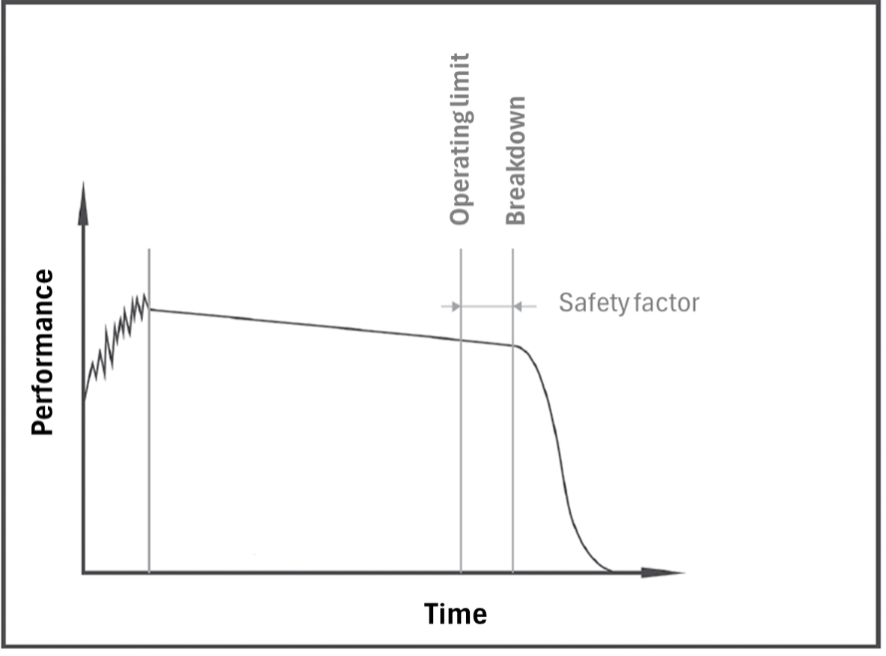

“Impossible,” he replies. “We have 11,000 items to maintain and calibrate, and we keep track of those electronically. A weekly schedule defines what to test, maintain, replace, and calibrate.” This is a cumbersome, but essential process to avoid breakdowns and machine or tools damage. As Jean Claude tells me, it is a trade-off: spend on maintenance, save on breakdowns.

Because nothing is static, Jean Claude’s approach is to go and see at the gemba often. “It's like the sails of a boat. You need to adjust them depending on sea and wind conditions. Sadly, as we lose our deep industrial expertise, more individuals make changes without fully comprehending their impact. Consequently, standards often discourage changes in settings. However, conditions vary, making adjustments necessary. I am not encouraging blind gambling, but I do promote confirmed knowledge,” he says.

“Every industrial process is naturally subject to small, often invisible variations over time, caused by environmental and material factors. For example, temperature, humidity, and oxygen concentration affect how materials behave during production. Water quality varies with groundwater sources and seasons. Even grease degrades over time,” Jean Claude continues. “You need to accept these drifts and learn to measure them.”

Sintering, for example, requires a very specific temperature: their work on performance for Aerospace led them to set up a SAT (System Accuracy Test) every three months. A second calibrated thermocouple is installed parallel to the one they want to test, to check the drift, if any. All machines with thermocouples are now systematically designed with a second thermocouple connection for this type of SAT.

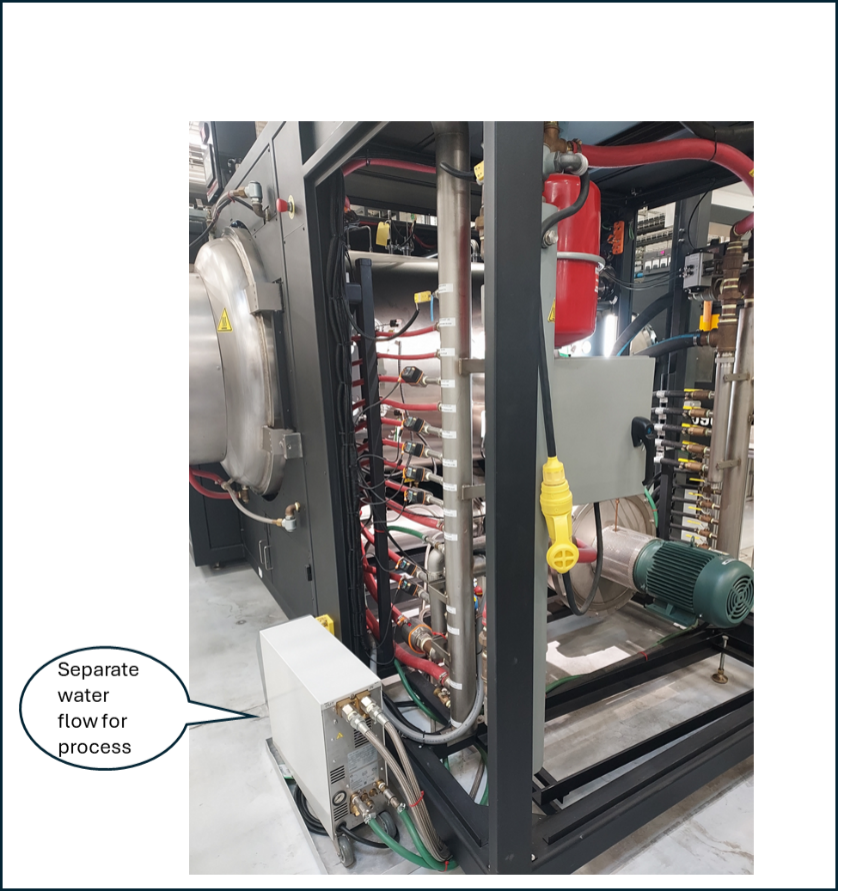

Jean Claude actually views most of his machines as fluid transport systems. “Alliance MIM adjusters need to understand notions of fluid mechanics,” he explains, “and the effects of changes in pipe sections, derivatives, and temperature.” We move over to a sintering furnace with a water circuit that both cools different parts of the furnace and feeds the binder trap to remove the last binder, called backbone. Jean Claude, with his background in Materials Engineering and Solid-State Chemistry, knew that two distinct functions, cooling and chemistry, needed two separate circuits. So, he designed the latest furnaces with two separate water circuits to improve process stability.

Drifts can also derive from shocks. During the Covid shutdowns, Jean Claude sometimes had to take over a supervision function. He spotted a team leader trying to adjust machines that had in fact been misaligned or warped by an impact during production. The shocks had not been reported. The team leader had covered them up and had been tinkering with the machine as best he could to adjust it. But a machine that is out of alignment by 3/10ths is no longer suitable for a part with a tolerance of 2/100ths. Adjusting it is useless; you must solve the misalignment issue first.

LEARN FROM MATERIAL LOSS

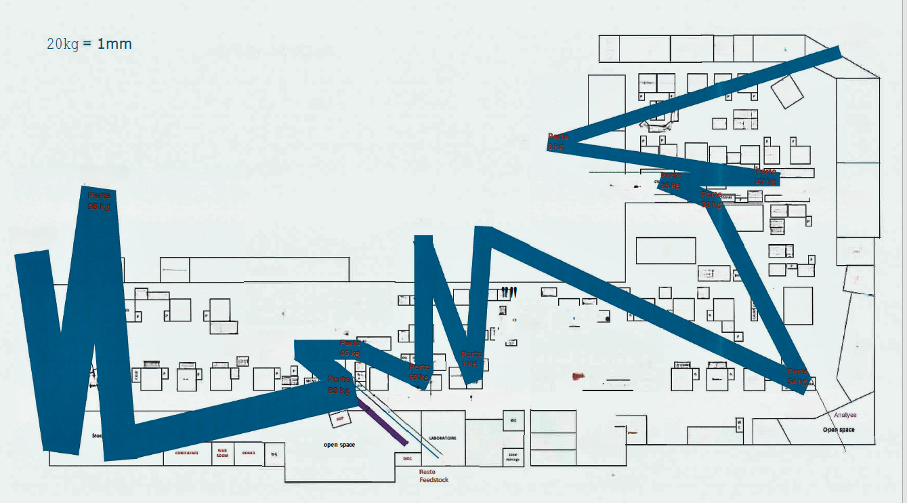

Jean Claude is also studying material loss closely and throughout the process, from the feedstock manufacturer, to whom the metal powder is entrusted, to the finished product exiting the plant. Inspired by Minard’s famous graph depicting the progressive attrition of Napoleon’s army during the Russian campaign - correlating troop numbers with geography and temperature - Jean Claude created a similar visualization for each of his feedstocks as they move through the plant.

The largest material loss occurs during feedstock manufacturing (from metal powder to the bound feedstock). One of Alliance MIM’s customers, concerned about over-reliance on a feedstock supplier, is funding a production line directly within their workshop. Once the line becomes operational, it will allow deeper observation and understanding of the process.

Other losses derive from machine adjustments, stabilization of first parts after mould changes, chips, scraps. Jean Claude is always keen to dig deeper.

VISIBLE KNOWLEDGE

Now, is all this extensive knowledge on machines and materials solely in the head of Doctor Jean Claude Bihr? It isn’t. Jean Claude is pushing his teams, both in production and engineering, to learn by problem solving.

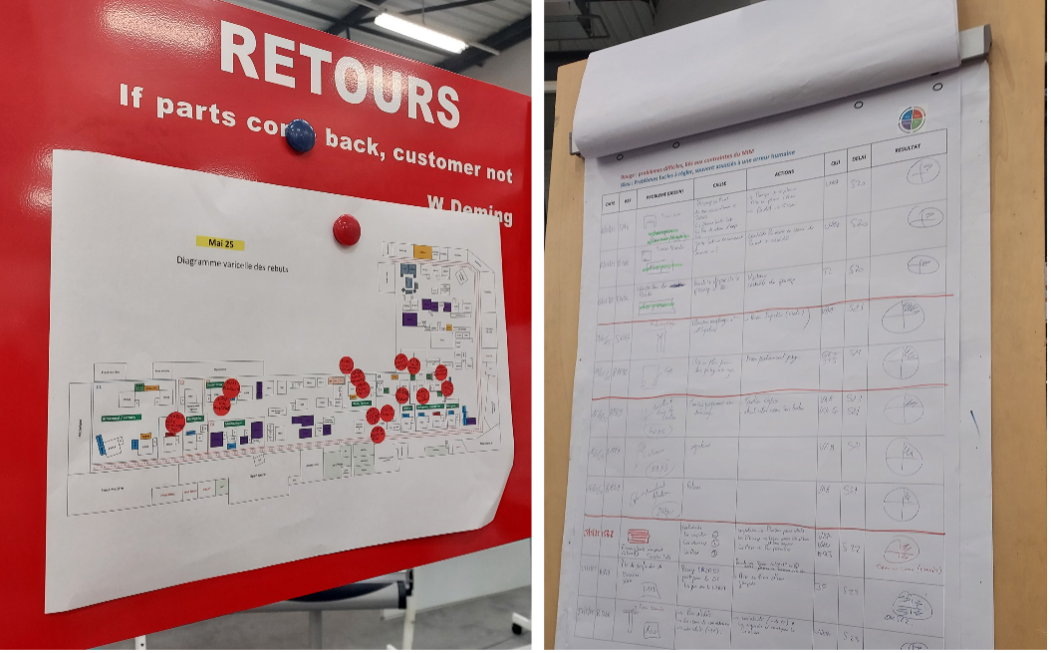

We are back at the heart of the workshop, the red bins area, showing both a chickenpox pattern of where the non-quality issues were created in the plant and the associated problem-solving exercise. This is where deep learning takes place.

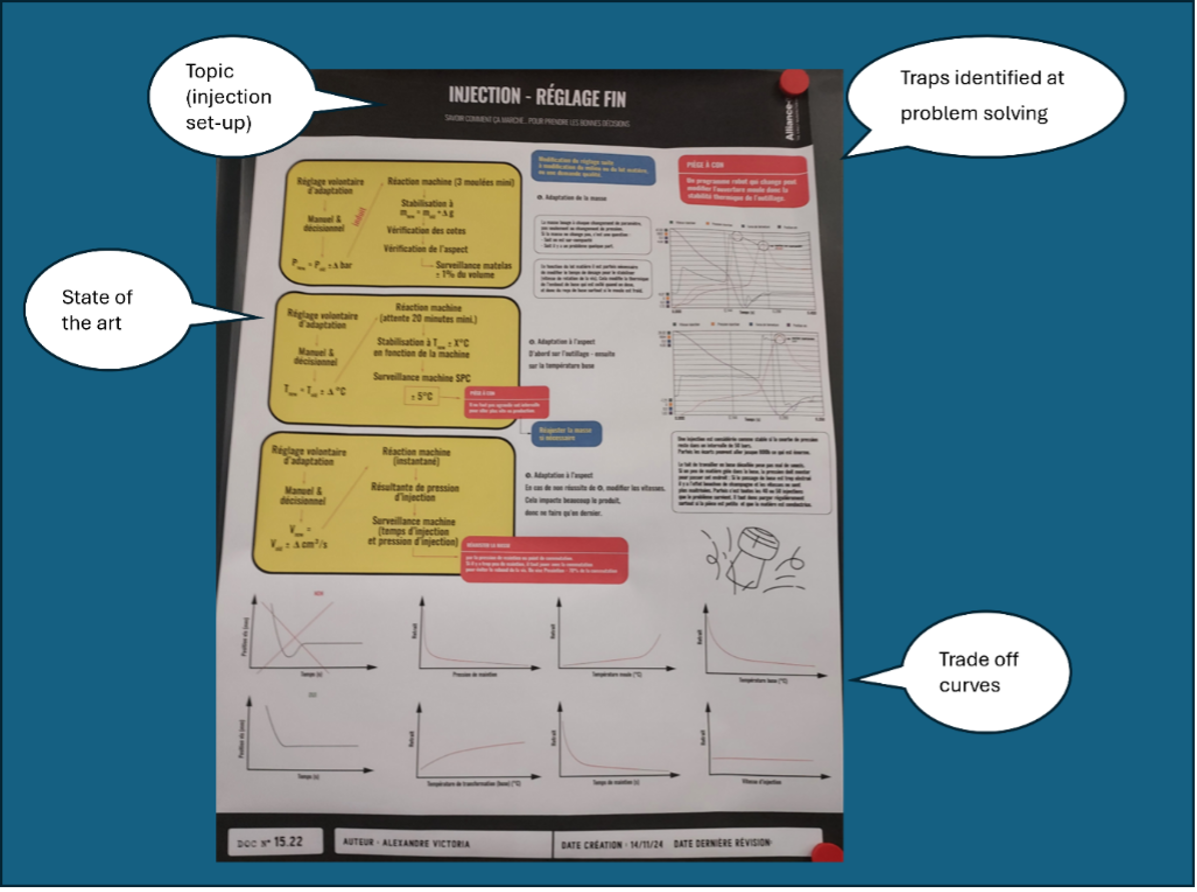

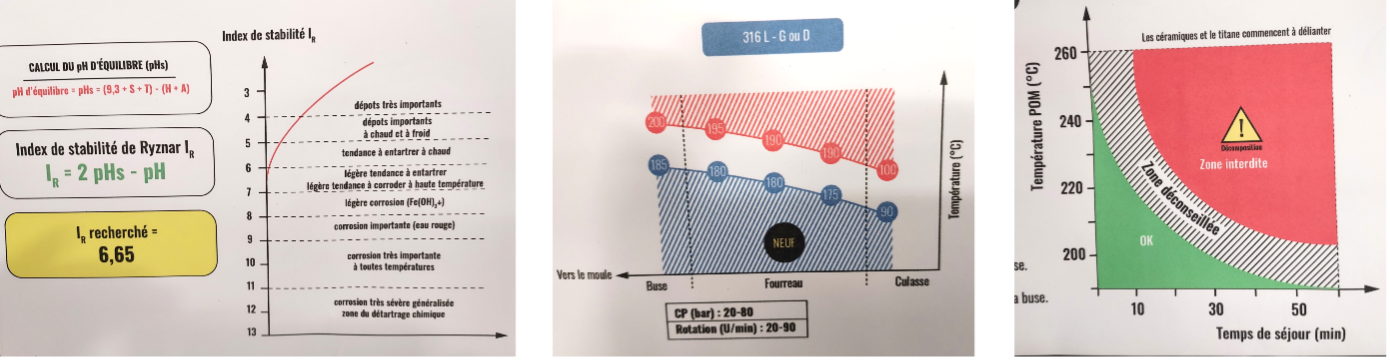

Inspired by Allen Ward's book Visible Knowledge for Flawless Design and similar posters in the Toyota Nagoya Museum, Jean Claude encouraged his teams to document and share their collective knowledge of plant processes. They created large knowledge boards on topics like injection, thermocouples, mould positioning, and sintering furnaces, capturing the state of the art and insights from problem-solving.

Most include trade-off curves showing for instance the extent of the part’s shrinkage after sintering, according to the temperature in the furnace, the pressure or the time, based on their own experience.

Other trade-off curves, whether computed by Alliance MIM or others, remind them of what works and what does not, and where quality lies.

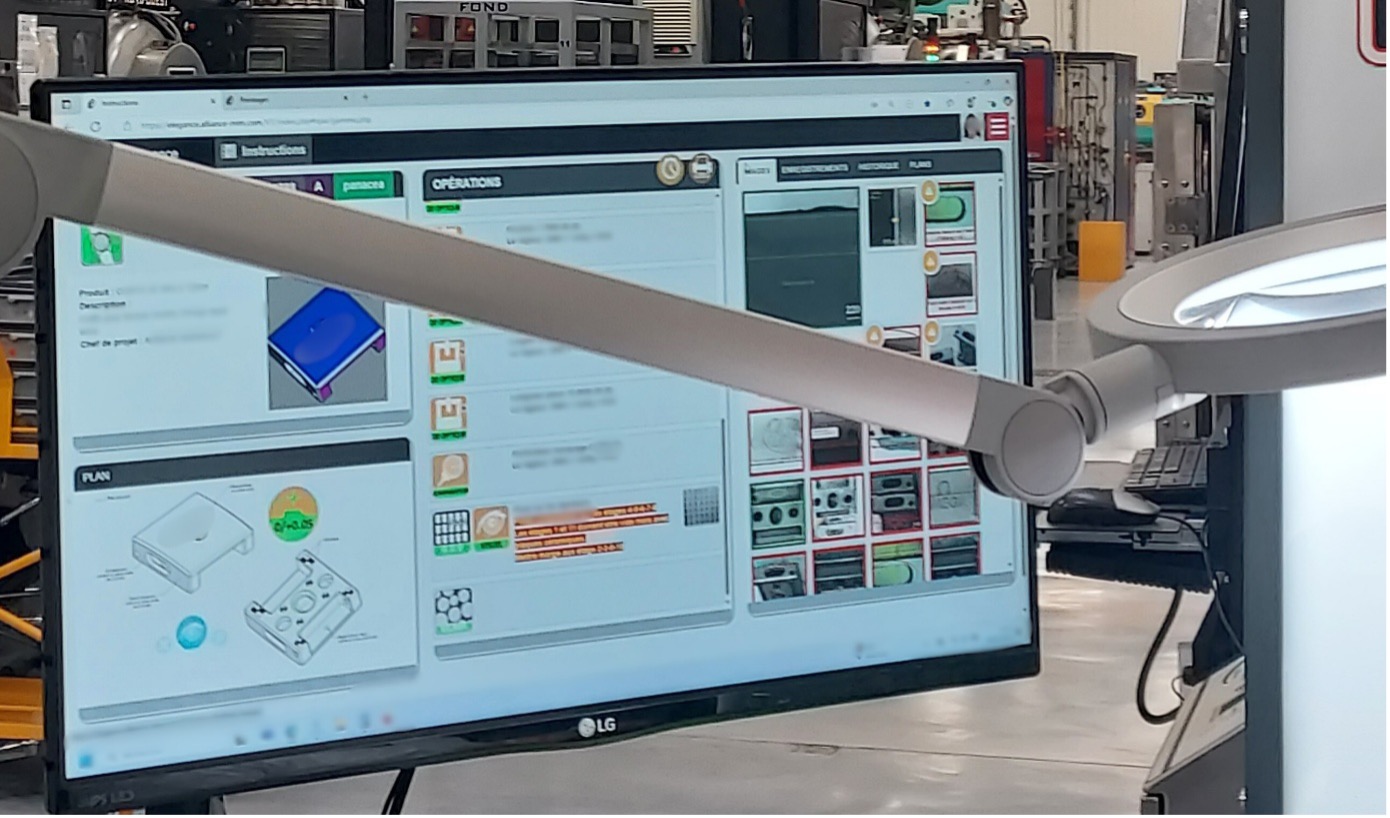

Operators also benefit from extensive learning through problem solving. Their workstations display a detailed default folder for the very part they are working on, as well as warnings on each step of the operation.

“There is science behind all this, Jean Claude insists. “I see ourselves as craftsmen, not tinkerers.”

PREDICTIVE DESIGN AND TARGET COSTING

The tour concludes in the Engineering department. The teams here extensively learn from manufacturing processes and have contributed significantly to the information available on the knowledge boards. There is a constant stream of engineering kaizen in the plant to stabilize the operations, which stems from observation on the gemba and the ensuing improvement ideas.

Trade-off curves, in turn, assist them in designing more efficiently while maintaining cost control. Jean Claude shows me the Target Costing board, which is used for every project. The math is simple: the customer funds the mould at a set price, design decisions and test results accumulate design costs, and the final balance at the end of the project must be positive. This board is monitored on a weekly basis for each product.

THE FABLESS PRINCIPLE MAKES NO SENSE

I cannot resist quoting Jean Claude’s latest publication Le Lean de l’Intérieur (Lean from the Inside), Jean Claude’s latest publication in which he documents his experiences, insights, and discussions with sensei Freddy Ballé, Isao Yoshino, and Masamoto Amezawa. (In 2021, he had published Le Lean Aujourd’hui (Lean Today) in France, a fiction inspired by the Training Within Industry book Job Relations).

“The workshop is the testing ground for engineering, so the fabless principle makes no sense,” I read out from the book. I wish more of our industrial leaders had spent time in production before they decided to relocate it in low-cost countries. Engineering without learning from manufacturing cannot work properly. And, as we are discovering now, manufacturing that has relocated to China or elsewhere is perfectly able to develop its own know-how in design through reverse engineering.

The close collaboration between Manufacturing and Engineering, the never-ending search of why things happen the way they happen, the thirst for a deep understanding of processes and materials… These are essential components of a successful company in a very challenging market. Our competitors in China have done it. We can do it too, as Alliance MIM’s story brilliantly demonstrates.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

THE LEAN BAKERY - For the past decade, lean has fuelled the growth of a chain of cafes/bakeries in Barcelona. With 100 now open, the Retail Manager explains how lean helps them manage a booming business.

FEATURE - This story from a Chinese children's hospital reminds us that the lean healthcare improvements we make can have remarkable results on both patients and staff.

FEATURE – In this compelling read, the author discusses lean thinking as a system for learning that challenges our assumptions and tells us why blindly applying “best practices” takes us nowhere.

CASE STUDY - An approach based on Lean Daily Management System and experiments in a model area led an Italian manufacturer of combine-harvesters to become one of the leanest organizations in the Veneto region.

Read more

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – At GHU Paris, leadership pairs strategy with gemba visits, 5C problem-solving, and cross-functional learning to create a resilient, people-centered improvement culture in psychiatric care.

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – What’s kaizen for? Improving quality? Generating a flow of ideas? Challenging a method? All of the above, so long as the underlying goal is to make people’s lives easier.

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – Somfy’s R&D department is applying Lean Thinking to close knowledge gaps, improve collaboration, and boost innovation and technical competence.

CASE STUDY – Lean Thinking helped Bernard Controls Europe improve efficiency, reduce lead times, and enhance quality, fostering resilience in the post-pandemic industrial landscape.