Making gemba people’s life easier

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – What’s kaizen for? Improving quality? Generating a flow of ideas? Challenging a method? All of the above, so long as the underlying goal is to make people’s lives easier.

Words: Catherine Chabiron

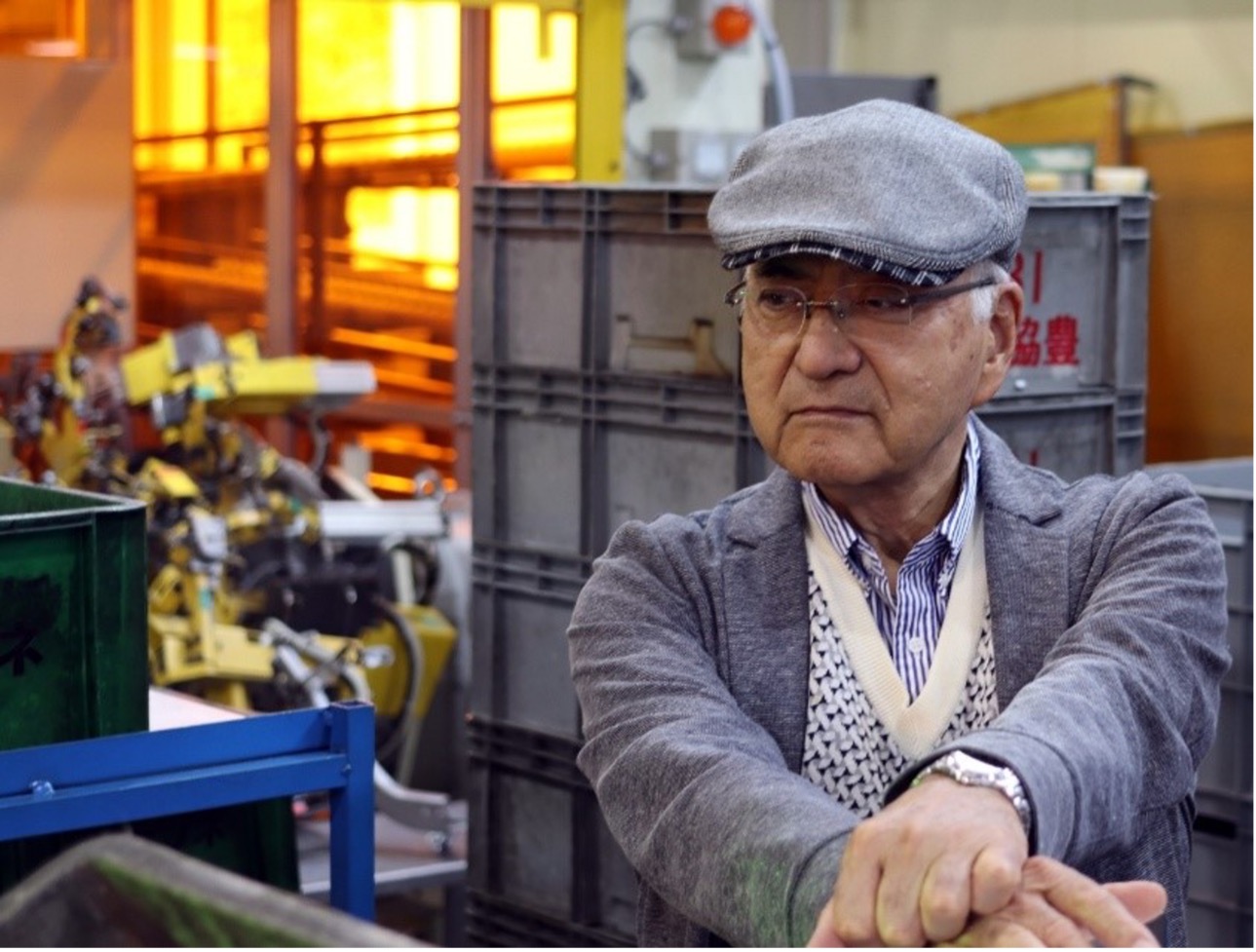

According to Amezawa-san, a retired Toyota leader with a lot of stories to tell about his experiences in US and Japan manufacturing plants, the main responsibility of plant management is to “make gemba people’s job easier”. Cumbersome tasks, complicated movements, and technical misconceptions can generate safety hazards, poor quality, lack of repeatability, and extra costs. In the same way, product or manufacturing engineers, maintenance, purchasing or supply chain can seriously disrupt the work on the line when they change a set-up or introduce new products, components or technologies. That’s why, Amezawa-san maintains, they need to support kaizen until production flows again and quality is up to expectation.

In the French lean community, we have been mulling this over for some time, which has triggered lively and enthusiastic exchanges on kaizen and led to a rich array of experiments on the line with and in support of operators.

This article will tell you about some of these recent kaizen efforts, developed at PCM Habilclass, AIO, Alliance MIM, Hellermann Tyton France, Thales and GE Healthcare France.

IMPROVE WORK AND QUALITY

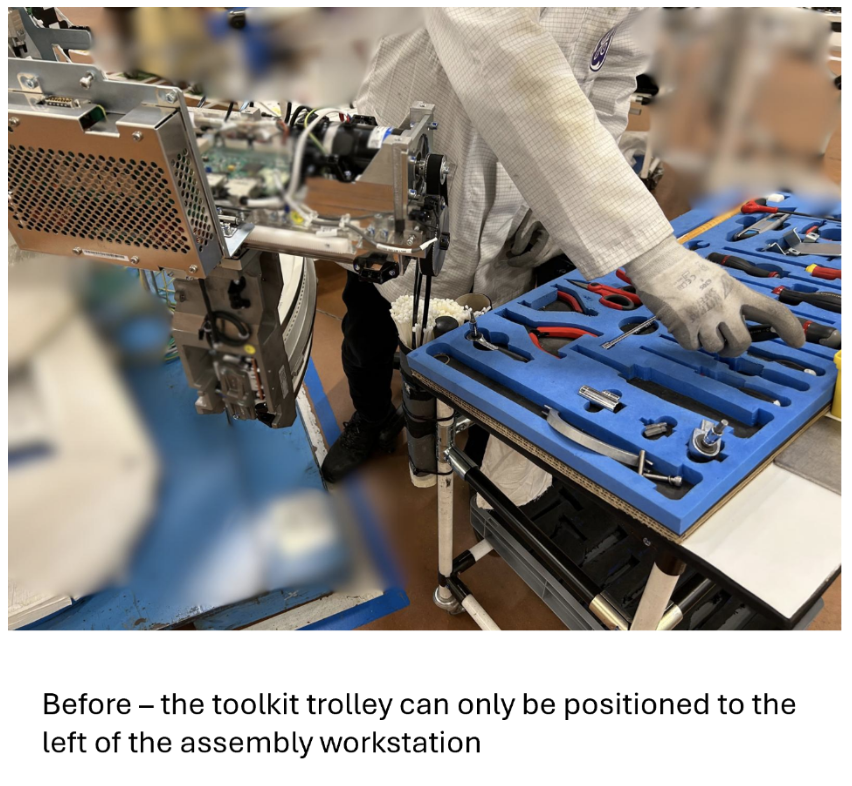

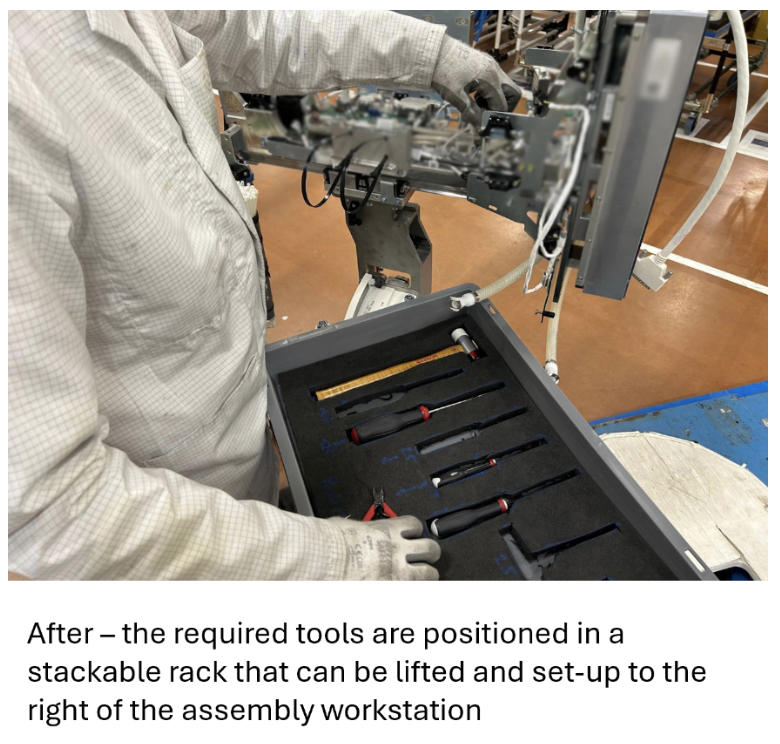

The first objective of kaizen is to improve the quality of the product while making the work easier to do. The following example of a 5S exercise with a control kit on wheels in PCM Habilclass is self-explanatory. A bit of 5S is often useful to facilitate work and reduce both motion and mental load.

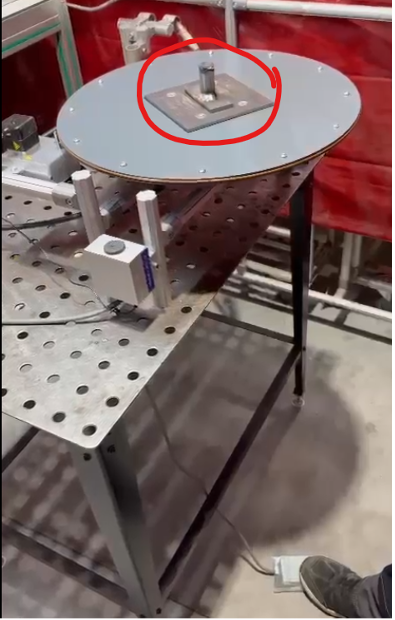

Manual welding of axles can be tricky as you need to weld evenly all around the axle. Hence the idea at AIO of building a turntable, triggered by foot, to make the work easier, weld all around at a regular pace and improve the quality of the welding (not yet at optimum on the picture, but improving).

You may argue that this is no innovation and that all sorts of welding equipment of the kind exist in the market already. But a home-made tool has three advantages:

- It is a low-cost solution and readily available.

- For the person who designed and built it, it’s a key source of satisfaction at work, and an opportunity to be recognized by peers and management.

- An implemented idea will generate another idea elsewhere, thus unleashing the flow of energy and creativity in the organization, as we experience in our community over and over again.

And remember: if external, more sophisticated solutions exist, the home-made tool can be conceived as a prototype to understand minimum requirements and constraints. But keep in mind that purchased equipment will often provide more functionalities than you need and may not easily adjust to your exact specifications.

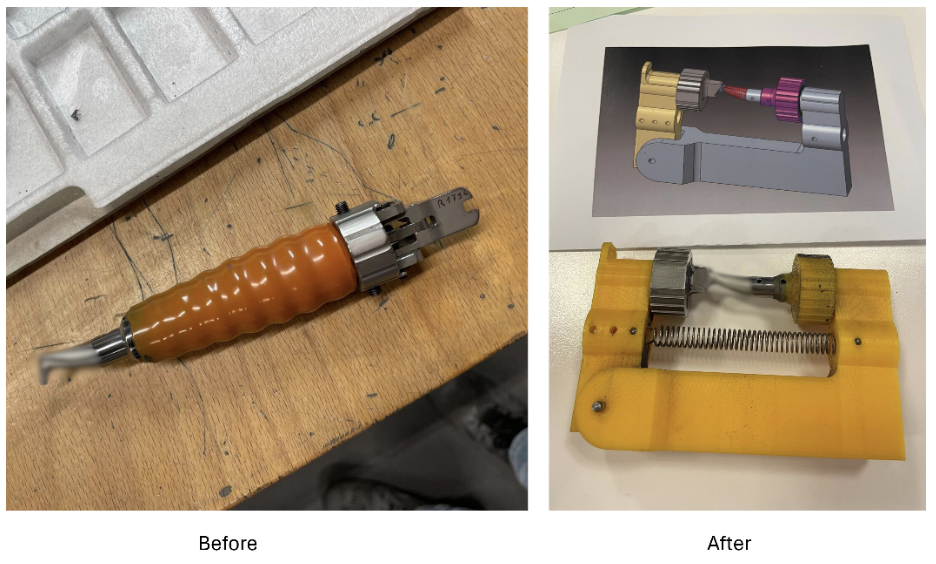

Let’s move to another example from Alliance MIM. Polishing a metal part requires a strong hold. Some of the operators found it hard to insert the part that needed polishing into the chuck and tighten it by hand. The action requires strength, time and is not very practical. Based on their observation, the teams came up with a 3D-printed tool that will ensure the required grip. Tightening by hand is replaced by a simple clip mechanism, and the rotation is powered.

Alliance MIM’s plant was one of the first I ever visited that had an active workshop on its premises, open 24/7, with 3D printing capabilities and a set of tools employees were encouraged to dabble with, to learn the trade and gain confidence. Some of them have gained such proficiency that they can now build an electric bike from scratch. This ability now proves extremely useful when a kaizen is needed.

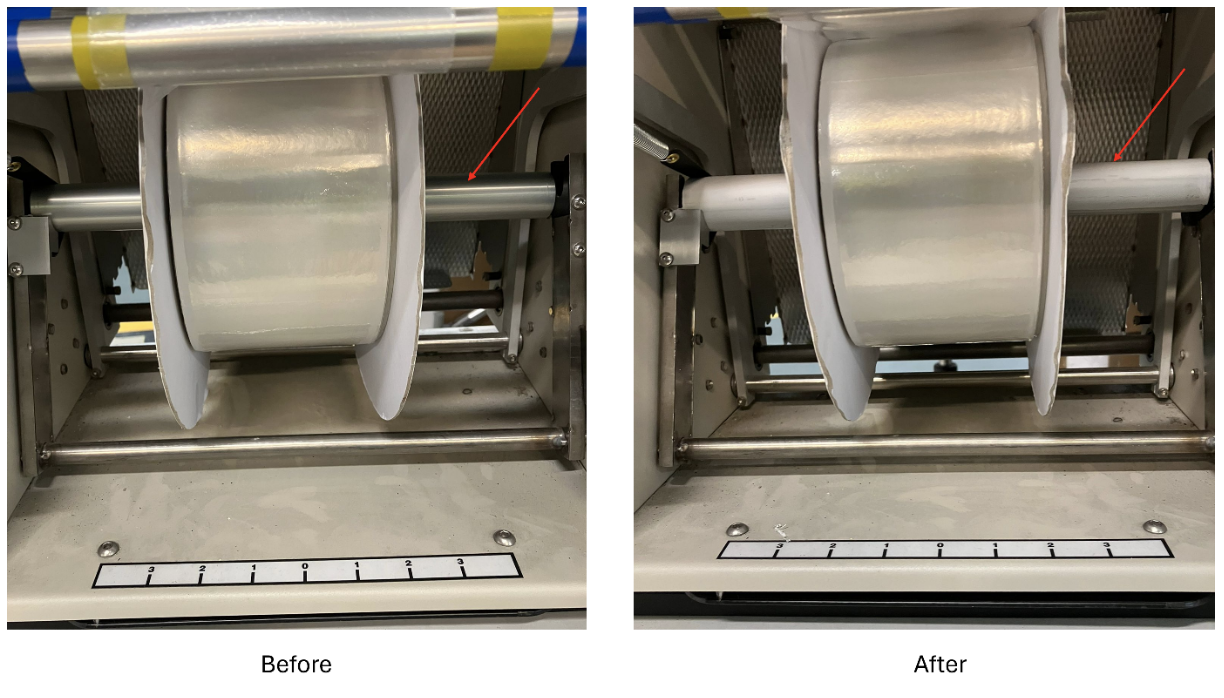

Kaizen will be needed every time there is a change somewhere. In this Hellermann Tyton example, plastic sachets required a print. The supplier had increased the diameter of the roll that supports the sachets, compromising the quality of printing as the roll was loose and moved along the rotation bar. This was not acceptable for the customer.

Operators found the countermeasure: measuring the diameter change and enlarging the rotation bar with plastic add-ons to tighten the roll and keep it centered.

MAKE MONEY

Kaizen is also a great way to make money. Making the work easier for people at the gemba usually improves quality but can also result in financial and time gains.

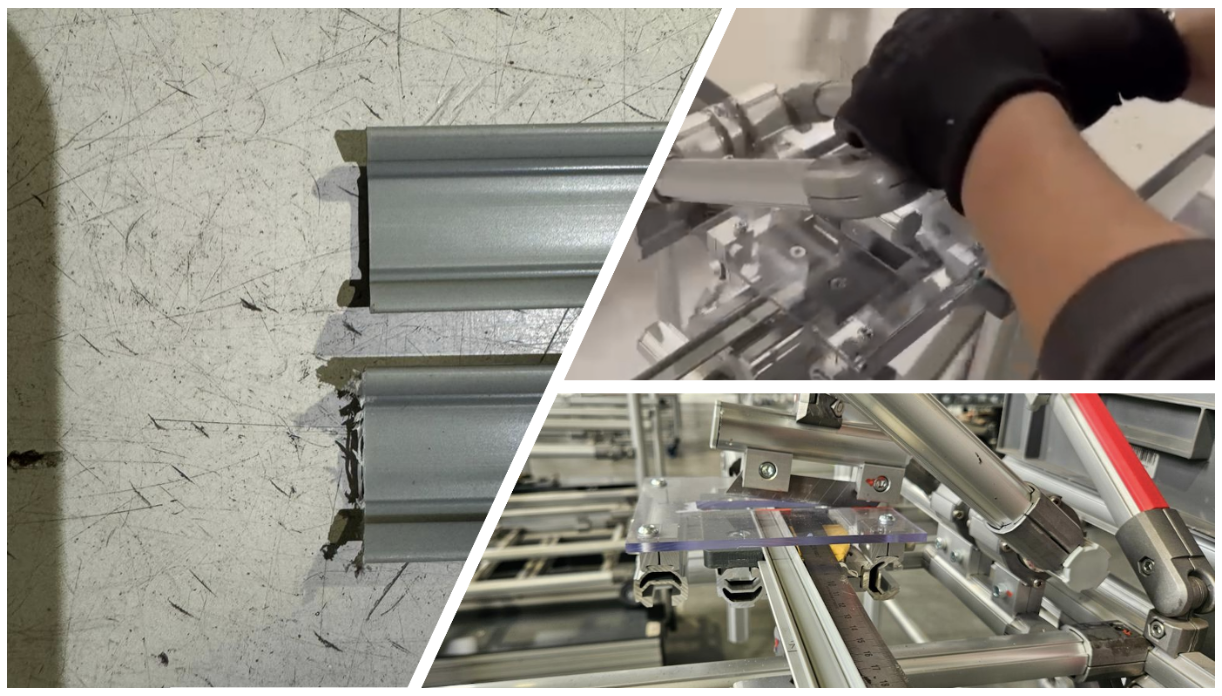

In our next example, the target of AIO was to facilitate a recurrent cutting operation, while improving the quality. It turned out that the new cutting installation halved the cycle time from 100 to 50 seconds. The team calculated they perform 15,000 such cutting operations per year and estimated a potential €20k gain per year. Not to mention the quality improvement!

Working on SMED (Single Minute Exchange of Dies) can also be profitable. PCM Habilclass, a company that designs and produces metal racks, has a folding machine that required five tool changes to operate on a two-column rack. A SMED workshop was launched and the teams found that two of the five tool changes could rapidly be avoided by changing the folding sequence. By adding clearances to the sheets, they found they could fold with the same tools. Two more tool changes were eliminated with the new approach. All in all, the number of tool changes is down to one, from the initial five. This represents around 5 minutes per rack, with a takt time of 20 such racks per day. The team calculated a gain of 366 operating hours per year.

The same company was having trouble with the capacity of their fiber laser machine, which often created a bottleneck. Investigation confirmed that the processing time was long because the number of holes to be drilled was very high. The team searched for a solution in vain, until an operator proposed to superpose two sheets and drill holes through both. The design team was doubtful, unsure the machine was designed for that. But they decided to give it a try (the sheets are 1 mm thick) and results turned out to be rather acceptable. They had to work on the machine set-ups, but the proposal turned out to be a very serious improvement track indeed.

The same machine could cut two sheets in 11 minutes instead of the 19 minutes required to cut them one at a time – a 40% productivity improvement and ultimately an investment in a new machine avoided.

GENERATE A FLOW OF IDEAS

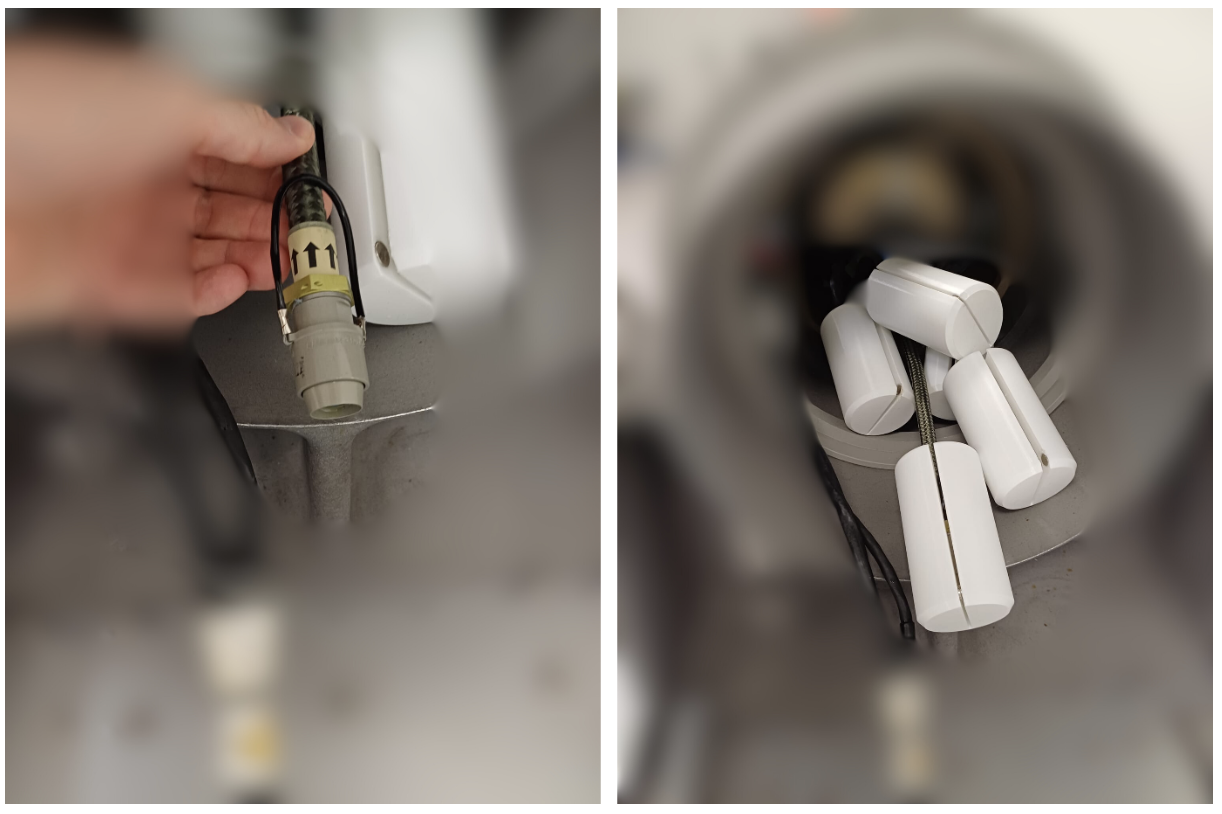

Connectors are fragile things, and a kaizen was launched in Thales to address recurrent breakages. Observation confirmed that these occurred on a system requiring five different connections. The team came up with a 3D-printed nozzle capable of adapting to the different connector shapes. The nozzle is made of rigid material on the inside and semi-rigid on the outside to cushion impacts. The nozzle costs next to nothing (around €1), a far cry from the cost of replacing broken connectors (around €1,000 per month) – not to mention the time spent on the replacement.

This kaizen raised a new question: “How good are we at executing our assembly sequence? Is there something we could improve?”. A kaizen triggered by a previous kaizen.

Successful ideas have a way of generating new ideas. Rather than simply deploying a best practice (the solution), increasing the scope of the issue you are trying to solve (and the solution you come up with) will trigger thinking elsewhere, and new solutions will arise.

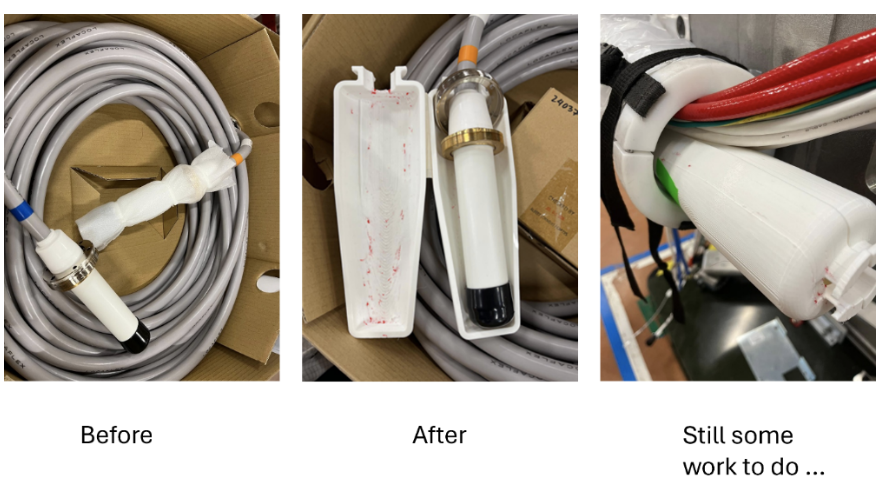

This is exactly what happened in our next story. The above Thales kaizen triggered another one, this time at GE Healthcare, after being discussed over WhatsApp by our community. An operator was observed spending close to two minutes to protect a socket: he would cut off the protecting paper, roll it around the socket and tighten it with plastic clamps – only to undo his work just a few hours later once the machine assembly was achieved.

The team had already thought about protection sockets, or about discussing with the supplier to have them cover the sockets with thermoformed protection (an extra cost). But inspired by the Thales nozzle kaizen, they decided to try with a 3D-printed cover and quickly test its feasibility.

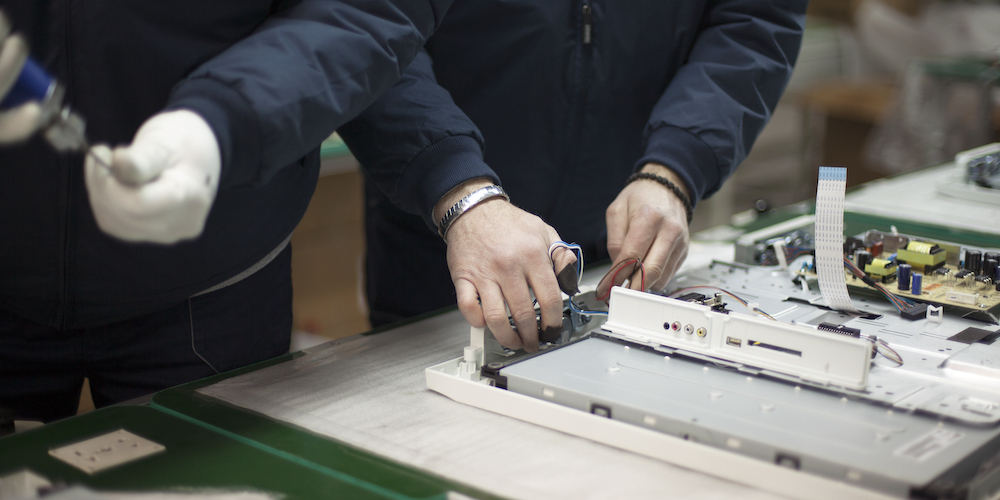

The first iteration confirmed it was ok but was rather cumbersome, given the volume that needed protecting. They had to add a clamp to avoid risks with magnets and electronic cards nearby. But when they tested the outfit in assembly, they discovered that the quick and dirty solution was not going to cut it this time, as shown on the third picture. Far from throwing in the towel, they are back to the drawing board to think the problem through.

CHALLENGE DESIGN OR METHOD

Kaizen is also an opportunity to challenge the design of the part or a method.

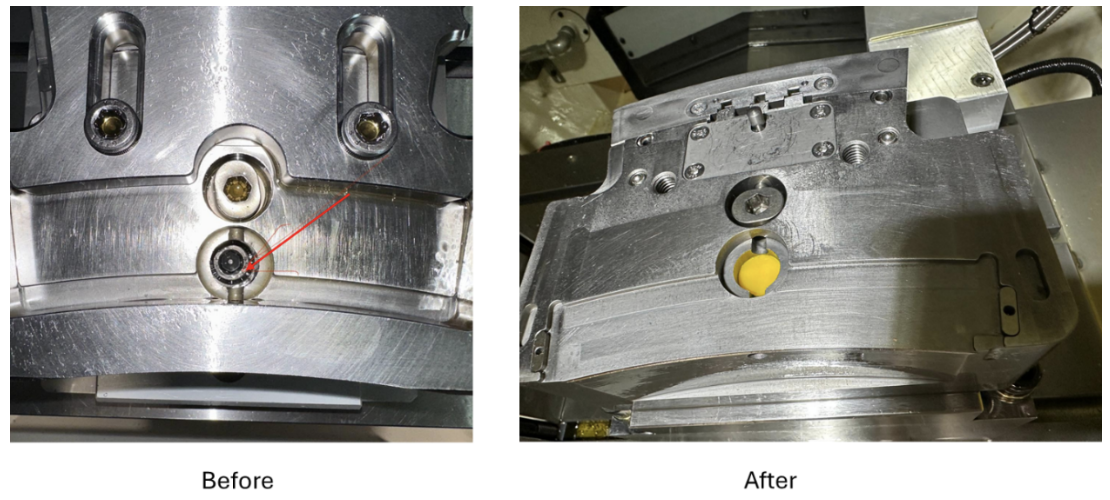

In this example, from Alliance MIM, we are looking at a part that needs to be clamped when machined. The latter operation usually leaves small chips over the part that must be manually removed. No one looked at the problem until automated unloading of the part was envisaged, to free the operator from having to do non-value work. Unfortunately, the cleaning operation prevented the unloading from being automated: the robot could easily take the part and remove the clamp, but it could not perform the clean-up.

The solution was to put a cache on the part during the machining, something that could have been introduced long before. This highlights the need to spend time on the gemba and observe non-value tasks.

The next example is also very interesting. A rolling crane has been installed in this GE Healthcare workshop, to move large and heavy parts between different assembly workstations. The wheels are fixed but the crane still tends to move away from its track when pushed from the left-hand side. Given the weight of the loaded crane, this creates a slight torque effect, forcing operators to shift it back into position at least once a week – both a waste of time and a painful effort. With the supplier unwilling to modify his crane, kaizen became the only option. It started with sticking double-sided tape to the rail to test the deviation and friction. The tape managed to hold for two weeks then gave way. They then switched to a steel angle that was fixed to the floor. Unfortunately, friction persists and can block the crane. A tape preventing friction has been added to the steel angle and this has reduced the effect.

While investigation on the issue continues, a new, key question has been raised: “Why do we have to move heavy parts six meters away with a crane? What is wrong with the layout of the assembly area?”

This is typical of a good 5 Why exercise: ask the question “why?” until you reach the misconception, the “I really thought it would be the best way” or the “We never seriously considered another option”.

Let me share another experience from the same company. The operator is working on an assembly workstation for a 20- to 25-minute cycle. He is assembling a complex X-ray machine for vascular surgery, using tools on a well-organized shadow board, itself the result of a kaizen. To reach the tools positioned on the left-hand side (there is no room on the right-hand side), he must either grab the tool with the right hand and pass it over to the left hand or bend over to reach the shadow board with his right hand. This is not ergonomic and generates a slight waste of time because of the extra motion.

The kaizen consists of a new shadow board (in grey in the next picture), that is stackable both on the tools trolley, when moving around, and on the conveyor to the right of the workstation, so that the operator can pick the tools to his right. The point is to bring tools closer to the operation to reduce operator movement.

The kaizen you see here has not been completed yet, as the team plans to rearrange the tools on the stackable shadow board to reduce wrist torsion.

When presented to our lean community, this kaizen prompted several interesting questions, like “Why so many tools?” It turns out that there is a huge number of screws because the machine has been designed that way by Product Engineering, and because subassemblies made by suppliers must be integrated. Not to mention the fact that each operator has his own preferred tools.

This is the story of many kaizens: gemba people must find ways to reduce the impact of poor designs or, rather, designs that were thought out without assembly risks and issues in mind. One of the community members, Jean Claude, tells a similar story: “In my company, the moulds used to be a mess. At the design office on CAD, everything looked fine. In the mould workshop, too. No stress, moulds were set flat at ambient temperature. On the press, in real life, it was another story. The mould is setup vertically, at 140°C, you end up cursing those small screws handled with heat-resistant gloves, at arm's length. The production team was screaming. The designers took the point and corrected.”

Lean engineering has taught us that a good product is also a product that’s easy to assemble in the workshop. The best way to check is to bring designers down to the workshop and organize a slow build to observe each assembly step. Much can be learned from this.

KAIZEN IS A CORE ACTIVITY

From the above, we can conclude that:

- Kaizen makes gemba people’s lives easier – a sure way to reduce safety risks, improve quality, and reduce lead-times.

- As a side effect, trust towards management increases and cooperation improves, since management demonstrates their sincere desire to help and support.

- Encouraging and praising kaizen leads to engagement and ownership.

- Kaizen helps avoid non-quality costs and unnecessary investments.

- Kaizen in A can generate a new idea in B, and this is how the flow of creativity starts, provided management supports and encourages it.

- Kaizen reveals poor design or methods, and product or manufacturing engineers should be encouraged to go to gemba to see the consequences of their decisions.

- The best object of kaizen is a kaizen already implemented, because as you dig further down, you learn more about your trade, a machine, people, methods, and collaboration. As we publish, some of the above improvements have already been reworked and improved.

Many thanks to Arnaud Georgieff (GE Healthcare France), Charles Bert (Thales), Cyril Dané (AIO), Jean Claude Bihr (Alliance MIM), Marc Antoine Guichard Hellermann Tyton France), Nicolas Guillemet (PCM Habilclass) for their active contribution.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

VIDEO - In February, a group of Lean Global Network coaches visited Coloplast's Parts Distribution Center in Hungary to help the local team improve the internal lead-time across the facility.

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN – Last month nations signed a greenhouse gas emissions deal – on paper, an insurance policy against climate change. But if action is to follow promises, the cost of the insurance premium, as perceived by voters and governments, must be lowered. Lean thinking can help.

COLUMN – With many of us about to leave for our summer vacations, the importance of planning (a holiday just like a business venture) could not be clearer. But objectives and potential problems should be identified before setting off.

COLUMN - For those working in the I.T. world, identifying waste can be tricky. However, starting by tackling over-production will help you to eliminate every other form of waste.

Read more

FEATURE – Two coaches from Italian company FPZ reflect on their role helping lean thinking spread across the company and its newly-acquired businesses.

OPINION – How many times, in the early stages of kaizen events, have you thought about giving up? Hang in there. As frustrating as they can be, they will also teach you a lot, says our Danish colleague.

FEATURE – Through kaizen, people can directly participate in the improvement work. But without a manager’s clear responsibility and follow-up, they will left alone with the consequences of the introduced changes.

ROUNDUP – This month, we look at the most effective lean improvement approach – kaizen – by looking back at some of our best articles on the subject.