The art and craft of kaizen

FEATURE – Through kaizen, people can directly participate in the improvement work. But without a manager’s clear responsibility and follow-up, they will left alone with the consequences of the introduced changes.

Words: Eivind Reke, Cyril Gras and Daryl Powell

Change for the better, self-sacrifice, continuous improvement. The art of Kaizen has many interpretations. But what if it's simpler than any of those? Every time we discuss lean with our Japanese friends, they are always fascinated by our elaborate interpretations of the words and concepts. For example, did you know that the kanji characters in the word kanban translate to “look closely at the wooden board”? Or that the kai in kaizen translates to “whipping oneself”? “Very interesting” and “very clever, too clever for me” are common quips we hear as we head down the rabbit hole of overthinking and overanalyzing what we don't understand. We are just as guilty as anyone else here, so we pass no blame: we are all trying to figure out this lean stuff. So, what if we take a step back and re-think the situation?

What is the unique element of kaizen that separates it from other improvement methodologies and concepts?

FROM RANDOM IMPROVEMENTS TO MAKING THE RIGHT THINGS BETTER

Let’s start with a story. Two of us, Eivind and Daryl, were recently visiting a company together with Michael Ballé as part of our annual gemba tour of Norway. This company had hired a lean guy as their production system manager and, as lean guys do, he set about making improvements, involving the operators and visualizing the flow. As we were visiting, he showed us some of the improvements that he was particularly pleased about, having removed unnecessary activities from manual operations in the production of one of the firm’s new products. They’d done many things, from kitting parts to balancing the work between stations and moving parts closer to the line. However, Michael sensed that they were not addressing the real issue – so, after the lean manager pressed the operators to participate in the discussion, the conversation shifted to engineering changes that had been made to the product. These changes led to some products being shipped with a small yet serious defect – one that could have serious repercussions on the customer. Several months later, the lean manager revealed that, after the gemba visit, he and the operators had tackled this issue and figured out a way to fix the defect through kaizen.

But why didn't they address it in the first place? And what does this mean for our understanding of kaizen?

Even though we can and probably should do kaizen to remove muri, mura, and muda from the process, the big gain in it lies in engineering changes and follow-up. First, the lean manager worked on the problem he thought was most important, removing variation from the process. Yet, Michael saw a different type of variation: engineering variation that stemmed from the engineering changes that had been made to the new product design, that the operators were left to deal with on their own and had no means of following up on, resulting in products that were sometimes good, sometimes bad. In the end, the problem turned out to be the lack of knowledge of the technical parameters among the operators, which led to some products being outside of the engineering tolerances, ultimately resulting in defects. Once the root-cause was identified and understood, the operators themselves developed a standardized work sheet with clear step-by-step instructions, the reason behind each step, and critical knowledge points.

HOME DELIVERIES

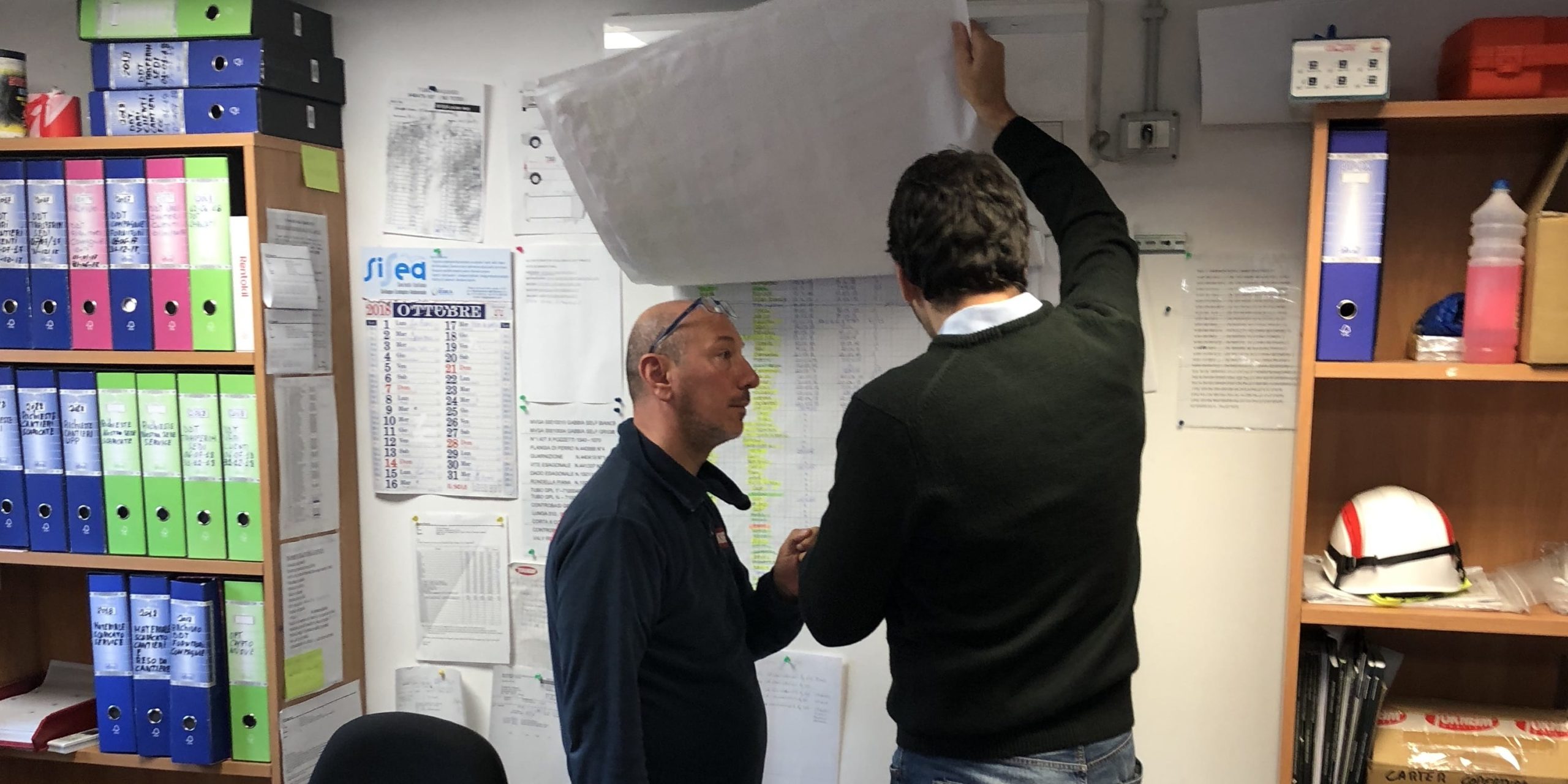

What feels like a long time ago now, back in 2016, Aramis Auto decided to make a big change to their product offering, which would require engineering big changes to both their logistics operation, their administrative operations, accounting, marketing, and design of the offer. They wanted to introduce home deliveries of the cars people bought online. The aim was to improve sales incrementally in areas of France that, at the time, were far from their outlets. The process was developed by a team of managers who needed to agree on how to operate it together. As always with new processes, things were not working as intended. Deliveries were late, lead-times were long, and customers were not satisfied. For a long time, the people in the process were left to deal with the problems and consequences of the big change on their own. However, Juliette, a former kaizen officer, came in to take over the operational role and when she arrived, she started to do a proper follow-up. Through kanban, she was able to identify one small problem after another, and together with the team she started to resolve them and form new ways of working that eventually led to on-time deliveries, shorter lead-times, and satisfied customers.

KAIZEN IS ENGINEERING CHANGES AND FOLLOW-UP

Funnily enough, the three books of Michael Ballé's The Goldmine trilogy are all about how people develop by dealing with engineering changes that in some way or another led to poor product quality, overburden, and wasteful processes. In The Goldmine, Phil struggles with how to fit the new product into the existing production processes. In The Lean Manager, Andrew needs to figure out how he can make his plant profitable by bringing in new products while making the old ones cheaper. And in Lead with Respect, Jane needs to find a way to change the software from one-size-fits all to a more flexible solution that can support the customer's business and not force them to comply with the IT system. This begs the question: why is it so hard for us to go down the engineering route when we do kaizen?

Lean did not originate in Europe or in the US. Yes, German engineers introduced the concept of takt-time to Japanese engineers. Yes, Kiichiro Toyoda visited the US and was inspired by the moving assembly line perfected by Henry Ford. And yes, Toyota discovered the TWI program after the war and was inspired by Deming’s famous lectures in Japan. However, pinning the origin of lean to any of these events would be like the famous sketch in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, where Brian finally gets rid of his unwanted followers but loses a sandal in the process. The crowd then immediately starts to interpret the event in their unique way, claiming it to be the right way. Lean originated in the Mikawa district, where Sakichii Toyoda tried to make life easier for his mother – one engineering change at a time. This same process led to the famous Jidoka innovation, which in turn financed the Toyoda family’s entrance into the automobile market. So, what if we took a new look at kaizen, ignoring our Western perspective for once and trying to understand it from the point of view of its uniquely Buddhist, Confucianist and Taoist origins?

It's easy to think that lean and kaizen will help us fix our messy systems that are stable, yet, well, messy. However, in Buddhism, nothing is stable and there is only change. And guess what, kaizen means change – hopefully for the better – but it also entails follow-up and ownership. It calls for us to own the change and follow up on it to make sure that it works in the real world, before moving on to the next change. On its part, Taoism looks for the simplest way of doing something by following the examples of nature. It prompts us to ask ourselves how we can follow-up in an easy and timely manner, without fuzz, while Confucianism considers doing things correctly by following the right behavior or ritual according to the right situation. So, what would be the right ritual or behavior for engineering changes and follow-up? On the other hand, Western business management, with its emphasis on functions and silos, has taught us that the most senior managers are responsible for defining and deciding the change, that middle managers are responsible for implementing the change, and that (they never tell you this part) front-line staff are left to deal with the consequences of the change. Classic AFP management as it was dubbed in Harley Davidson: Another Fine Program…

A recent, casual conversation we had at a conference gala dinner with a Toyota Plant manager revealed something interesting, when we asked him about something we’d seen while visiting Toyota plants in Japan. “Why are there so many people on the line discussing stuff with the operators?” we asked. We knew that engineers from the technical department frequently visit the production line to learn about their design, but we hadn’t realized how formalized a milestone this is, and with clear ownership. The plant manager told us that the engineer discussing with the operator is probably verifying an engineering change she has made, something she is expected to do. This means that the kaizen approach to change is that the engineer or manager who makes the change really owns that change and is responsible for making it work for front-line people as well – making sure that the work of operators becomes easier, not harder – and ensuring that the quality of the product (or service) gets better, not worse for the customer. The same goes for changes to production processes or organizational changes. There is clear ownership to form the change and make sure it works, for the better, and as a result develop both the business and people in tandem.

CONCLUSION

We really believe that lean is all about people, but people centricity without clear engineering responsibility will lead us to make changes in all directions without improving the overall system. So, what is the compass that guides us in making the right changes that will have an impact on our business performance? This is where lean becomes strategic, and where our approach to strategy changes. Instead of leaving employees to deal with the consequences of our changes, we go and see, to find and face the consequences of our changes. This entails accepting that what we think will happen and what actually happens is often not the same. Find and face means accepting and fixing the consequences of our changes and recognizing that front-line employees should not be left to deal with them alone. Take ownership of engineering change and follow-up, to make things better for customers, operators, and the planet.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – Based on their experience supporting the stellar growth of Aramis Group, the authors discuss the role of leaders in shaping minds and behaviors and constantly challenging themselves to be the best example they can.

EVENT LAUNCH - Save the date! The Lean Global Connection 2024 will take place on November 21 and 22. In this article, our editor introduces the event's theme and tells us what attendees can expect from the largest online lean event in the world.

FEATURE - The author explains how a recent book on radical quality improvement in manufacturing inspired him to initiate similar experiments in his software development firm.

COLUMN – In her first column, the author reflects on the role of leadership in striking a balance between the enthusiasm for change and the need to involve everyone in a transformation.

Read more

ROUNDUP – This month, we look at the most effective lean improvement approach – kaizen – by looking back at some of our best articles on the subject.

FEATURE – As she packs before leaving Botswana, the author tells us of a wonderful example of Lean Thinking that resurfaced from her past working in the Botswana tourism industry.

FEATURE – Innovation is a process and lean thinking allows that process to take place, by empowering everyone in the company to think creatively about solving customer problems.

FEATURE – When we emphasize systems and roles but fail to encourage and support kaizen, we cannot expect to tap into the full potential of Lean Thinking as a cognitive revolution.