Is radical quality possible in the tech industry?

FEATURE - The author explains how a recent book on radical quality improvement in manufacturing inspired him to initiate similar experiments in his software development firm.

Words: Woody Rousseau, CTO, Sipios

A couple of weeks ago, I was attending a Kaizen workshop that focused on reducing the lead-time for delivering a batch of software features to our customer.

At Sipios, we design and code websites serving organizations in the financial sector. For this specific customer, our team would deliver features to end-users on a weekly basis. The delivery process starts on Thursdays at 12PM, with an expected lead-time of 3 days. However, for the last few deliveries, it ended up taking around twice as long, causing major issues for both our customer and our teams:

- skipped or delayed deliveries of critical features;

- waste due to the quality department having to verify every single feature of the application several time at the final inspection stage;

- frequent interruptions for software developers working on the next features.

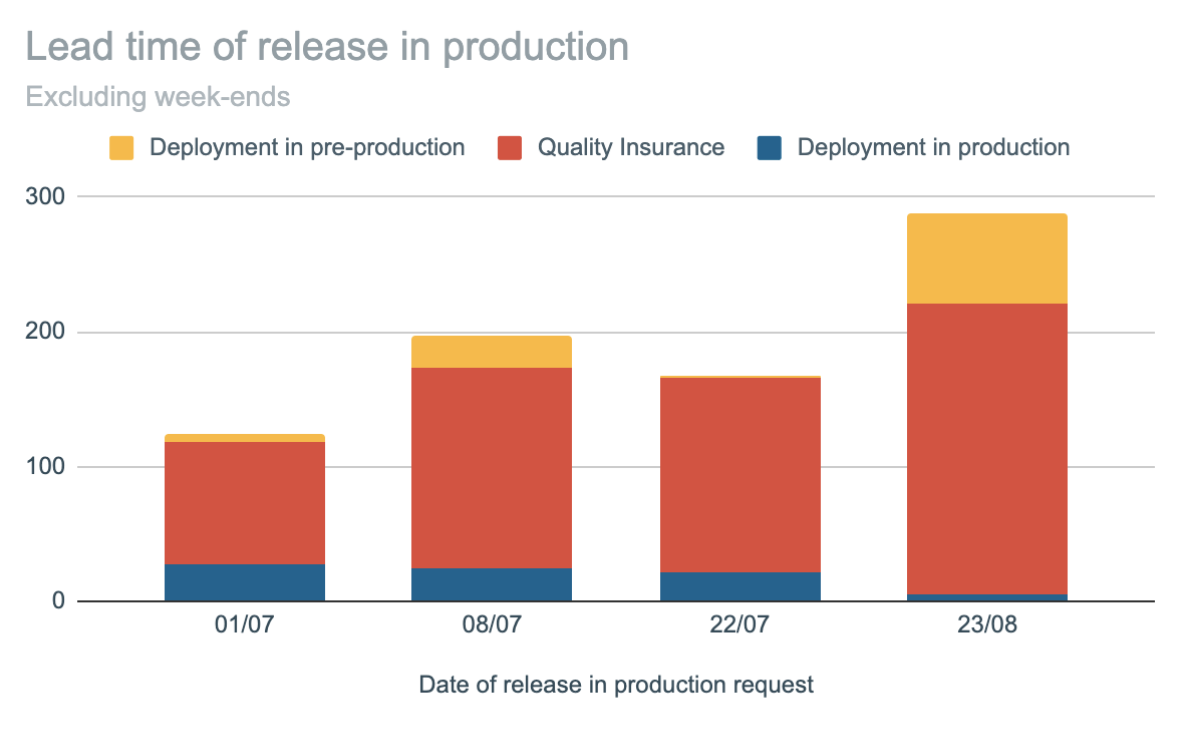

The increasing lead-times for releasing a batch of features to customers

The reason for this extended lead-time was quality defects, called bugs in our industry. Not only were there many of them, but I was also surprised to see that teams were not prioritizing fixing and learning from those defects and often preferred working on upcoming features.

That Kaizen session hit me hard, as it helped me realize that, as a CTO, I was not creating a culture of "Quality First" in the company.

Coincidentally, I had just heard about Sadao Nomura and his Dantotsu method, the radical approach to quality improvement described in his book The Toyota Way of Dantotsu Radical Quality Improvement. Dantotsu allowed Nomura-san to achieve exceptional results in all the Toyota Material Handling factories he supported.

For us in the digital industry, the Dantotsu approach can be compared to Extreme Programming, a set of techniques used to achieve low levels of defects when writing software. As I read Nomura’s book, I got increasingly enthusiastic at the prospect of trying this method at Sipios.

In this article, I’d like to share the main lessons I learned from reading the book and how, in my mind, these can apply to the tech industry.

THE 8-STEP PROCEDURE TO PREVENT DEFECTS RECURRENCE

Simply speaking, applying Nomura’s 8-step method means to take every quality defect occurring in manufacturing through a full PDCA cycle in just 24 hours. As Nomura-san says: “Speed is the key.” In practice, this means that to fix a problem, root-cause analysis has to be performed, the identified countermeasure deployed, and horizontal deployment initiated swiftly through collaboration with the Quality Assurance function.

This is very different to the typical approach that exists in the tech industry, in which:

- only high-impact defects (those, for example, causing website outage or preventing the end user from performing basic tasks on the website) are given a thorough analysis, called a Post Mortem;

- post mortems don’t include a root-cause analysis and never result in the identification of skill that is missing from the team and that caused the problem in the first place. The countermeasures will usually strengthen inspection by adding automated testing steps to avoid the bug from outflowing again to customers, but they will rarely trigger the creation of a standard or training for software engineers;

- post mortems define long-term countermeasures that are typically executed in the coming days or weeks, but never on the same day.

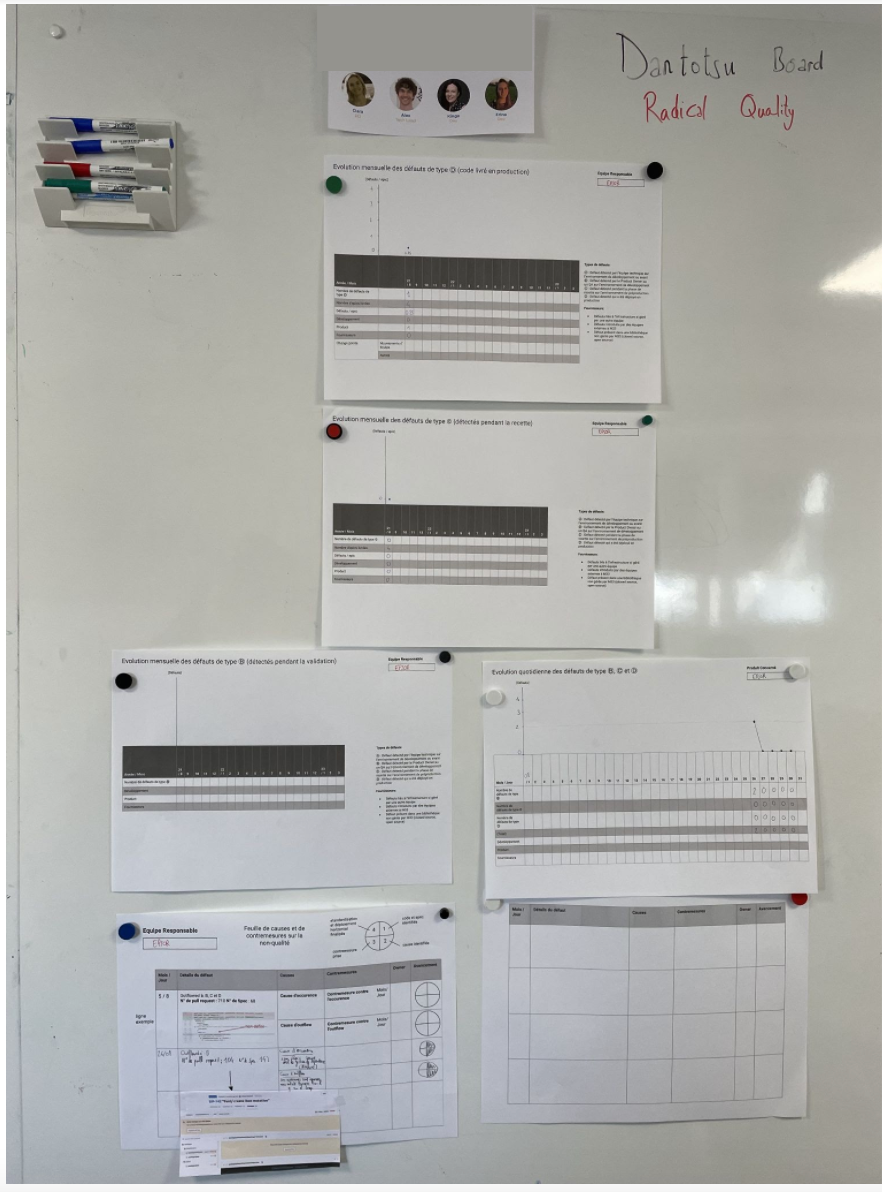

BUILDING VISUAL MANAGEMENT FOR RADICAL QUALITY

To visualize defects, targets as well as defect-related problem solving exercises, Nomura-san puts a lot of emphasis on visual management. This is to be expected in a lean book, but two elements really struck me. First of all, the fact that the computers are not allowed and defects are always analyzed physically, notably on a Quality Management board. Secondly, the way defects are divided into two categories - those coming from manufacturing and those coming from the technical department.

Once again, the tech industry does this in a very different way:

- bugs are usually tracked using software like as Jira or Trello - the same tools tech teams use to manage feature development tasks;

- There is no clear separation between engineering and production, even though there are great benefits to be reaped from distinguishing between coding mistakes and software design mistakes (like wrong specifications, defective architecture or choices in technologies).

PREVENTING DEFECTS FOR NEW GENERATIONS OF PRODUCTS

A challenge Nomura-san faced was defect prevention at a time when production of a new forklift model began. At this point in the book, one would assume that quality is always the priority, regardless of deadlines. Instead, Nomura explains how launching mass production of a new model should take 24 months and that the deadline cannot be missed.

The described strategy to achieve this focuses on prevention, to avoid as much as possible detecting defects during mass production or, worse, when the vehicle reaches the market and is in the hands of the end-user.

Nomura introduced Simultaneous Engineering Manuals (SE Manuals) for incorporating learnings from previously introduced models (VA/VE), including manufacturing constraints. This allowed the teams he supported to catch more and more defects at the design stage of the new model.

In the tech industry, too, many defects are only found once a new website is released. They are usually the same type of defect for each new website launch: servers not properly configured, missing edge cases due to rushing the work to meet a deadline, or failing to handle a high-than-expected number of end users visiting the website.

The application of SE Manual is not easy to translate into measures we can adopt in the tech industry, but if we look at VA/VE we can say we should focus on:

- identifying the sections of the code where bugs are prevalent. This likely means that the features behind it are complex and should be either automated or avoided in future generations of products;

- taking into account features that are already built in other websites, ideally reusing code whose quality is already “tested and certified”;

- creating more standards, especially relating to the release of a new website.

In conclusion, I consider Nomura's method a game changer. It teaches us that there is no shortcut to reach high levels of quality. As a CTO, this makes me want to raise the quality bar in the whole tech industry, where bugs are viewed as unavoidable time wasters. “Zero bugs” is the true way to go!

My team and I have already started to build visual management to try out Dantotsu at Sipios. I am hoping to be able to write a follow-up article soon to share with you the results we are trying to achieve.

Nomura-san's new book is out! Read about the remarkable quality revolution he led at Toyota Material Handling sites and learn about the Dantotsu method in great detail.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – We are used to thinking of A3s mainly as a tool for problem solving. In this Q&A, you will learn about the experience of a San Francisco hospital using it for personal development.

FEATURE – CEOs need to see people as assets and transform their companies’ product development systems if they are to tap into the full potential of a lean strategy.

INTERVIEW – For the past year, agricultural equipment manufacturer John Deere Ibérica has worked to spread lean thinking to the supply chain. We met with them in Madrid to understand how they’re going about it.

INTERVIEW – Atlantis Foundries was able to achieve zero defects for three months in a row thanks to machine learning. Here’s why the human component can’t be discounted.