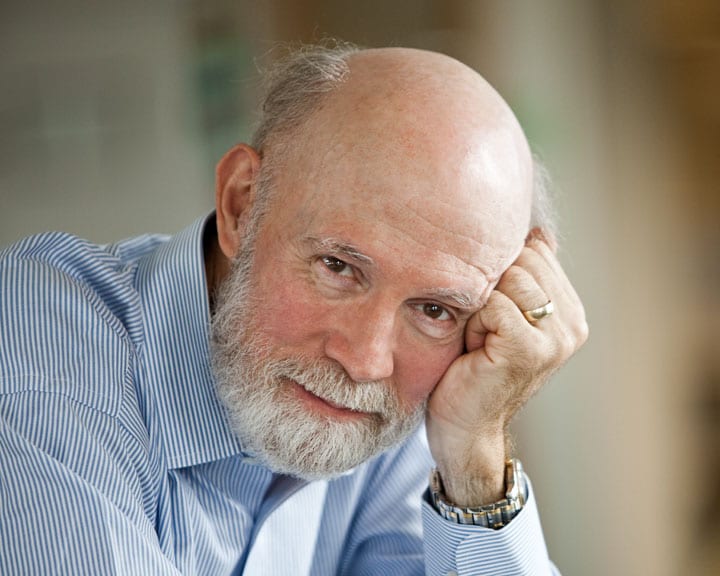

Jim Womack on what makes for a good lean employer

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – What does a lean employer look like? In this month’s column, the author reflects on the long-term commitment to employees a company engaged in lean thinking should make.

Words: Jim Womack, Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

Photo courtesy of cargol / Shutterstock.com

While organizing my thoughts for this year’s LEI Lean Transformation Summit in Nashville, I’ve been doing some forward thinking about the “lean employer”. What a pity that there are hardly any such creatures. And what might the Lean Community do about this?

But first, what do I mean by employers, much less lean employers? An employer is simply an organization that aligns its people (employees), often a very large number of people, to create value for customers. And employers that survive manage to create more value with their employees (as reflected by revenues from customers) than cost.

However, most employers today – let’s call them normal employers – are offering some value and a lot of waste to their customers. The manufactured product that works in the end but only after lots of rework and scrap. (Think Tesla.) The software that works in the end but only after lots of “upgrades” to fix the bugs in the original. (Think iPhone iOS.) Any product that only approximates customer desires rather than precisely addressing them. (The dealer who wants to sell you a car when what you really want is a one-stop solution to your mobility problem.)

What the customer wants is perfectly specified – pure value with no waste and bother – but currently the customer can only obtain a bundle containing both. This is bad for the customer but fortunate for the Lean Community because it is the opportunity space for lean thinking. By improving the value-creating work, after listening carefully to customer desires, we believe that lean enterprises can steadily convert current waste into future value.

However, doing this requires a social contract that keeps employer and employees working in harmony over extended periods of time. And this need is one that I feel often isn’t even noticed in the Lean Community, much less addressed. Improvement activities proceed without reference to the broader social context and mysteriously fail to stick.

For example, I was recently walking the gemba in a household name manufacturing firm that was attempting a lean transformation. They had just introduced a team leader system, so I asked one of the new team leaders how it was going. She pointed out that she had been laid off 14 times in 14 years due to the cyclicality of the industry and the she didn’t really know what a team leader was supposed to do. In a second firm, a small manufacturer in the Boston area also attempting a lean transformation, I asked the 25 employees on the shop floor (paid about $11 per hour) how many had a second job to make ends meet. 100% said they did. But what really surprised me was the production manager, who also had a second job to achieve his goal of a middle-class lifestyle. And my Uber driver to the airport yesterday is an ICU nurse in a famous Boston hospital who needs the extra money to make ends meet. (It made my day and broke my heart when she reported that the hospital’s lean initiative has changed her life.) Enough examples. This is this is a real issue.

In fact, these are examples of the behavior of “normal” employers today. They know they create a lot of waste in addition to value and they try to do better, often with a lean initiative, but they don’t protect their employees through economic cycles and industry disruptions. (“That would be very costly.”) The don’t upskill their employees, particularly with skills for jointly solving problems with the work. (“They will soon leave along with their skills.”) They accept wage levels set by labor markets. (“That’s how business works.”) And they have high turnover. Over time this leads to a downward spiral of declining responsibility to employees and declining loyalty from employees that has social as well as business consequences.

But can any employer actually do better? Can they create a social contract for lean to become a lean employer? Or are we only talking about unicorns? You will hardly be surprised to learn that I think Toyota can make this claim. The philosophy of the company is to hire at an early age (18 or 22 in most cases), promote from within, create a plan for every employee for their working life, and expect most employees to stay for life. (I learned a bit about this when I was the first person to hire a professional worker from NUMMI, in 1986. The Japanese managers were not so much angered as bewildered that I would recruit a young man – John Krafcik, now CEO of Waymo – to MIT when he could learn so much more by staying at NUMMI!)

To make this philosophy workable, Toyota has maintained a large reservoir of cash ever since its financial crisis in 1950, when it ran out of funds during a sharp contraction of the auto market in Japan and had to terminate 25% of its workforce to survive. This practice has been criticized by business school finance professors for nearly 70 years now as a failure by Toyota to fully leverage its financial power. But it permitted Toyota to endure the Great Recession and then the recall crisis of 2009-2010 without laying off a permanent employee anywhere in the world. And it is now allowing the company to methodically address the disruption in the automotive industry (soon to be the mobility industry) being caused by autonomy, low-carbon energy, asset sharing, and hyper connectivity. With its $87.5 billion in cash – three times that of any other auto company – it is financing massive concurrent engineering to experiment with a wide range of technologies (hydrogen fuel cells, solid state batteries), mobility concepts (autonomous delivery vehicles in cooperation with Amazon and Uber), and operational innovations (TPS-inspired lean software development to go beyond Agile and Scrum, and robotics that help production workers do their jobs better rather than eliminating their jobs.)

In sum, Toyota employees steadily create more value using fewer resources by jointly seeing waste and removing it and Toyota retains financial reserves created by its highly skilled employees to protect them going forward.

But perhaps no other companies can do this? While no one has executed the lean employer concept to the extent Toyota has, I see evidence that some are now trying. In The Good Jobs Strategy, Zeynep Ton provides cases on Trader Joe’s, Costco and Quik Fill in the US and Mercadona in Spain. In retail, entry-level, customer-facing jobs usually pay about $11/hour, but these firms have decided to ignore the labor market and pay wages at twice that level. To afford this they have multi-skilled and cross-trained their employees to permit steady 8-hour shifts, standardized their activities to facilitate improvement, built in slack time for every worker to be involved in improvement activities, and simplified their product offerings to those customers actually value. As a result, employees stick with their employers in an industry that often experiences 100% turnover per year and build skills to further improve their work. And they have a much more positive attitude toward customers – which I can attest to from personal experience – that grows sales and makes better wages compatible with healthy profits. Not yet Toyotas, but not normal employers either.

Perhaps you would like your organization to become not just lean in a technical sense, but also a lean employer? One word of caution about what is not sufficient: being a nice employer and being a good place to work.

A recent cautionary tale about niceness is Whole Foods. Co-founder John Mackey wrote a lovely book about this approach in the mid-2000s (Conscious Capitalism with Raj Sisodia), but nowhere in its 388 pages is improvement of the work ever mentioned or reduction of waste. When I read it, I was pretty certain that trouble lay ahead as soon as other grocers offered natural and organic product lines. This was because what I was seeing on store visits (I live near one of their Boston stores) was disorganization and struggling workers. They may have been treated nicely but they were not being trained to work efficiently and so it was not surprising last summer when Amazon ate Whole Foods whole. This was certainly not what John Mackey and Whole Foods employees had planned.

It seems common sense that managers would want their companies to be among the best places to work and Fortune magazine has been kind enough to provide an annual ranking of the 100 best places to work in the US, based on employee surveys. Looking at the results is quite interesting and, I think, a pretty good predictor of things to come. Top-ranked companies offer an exciting mission, high compensation for jobs of a given description, ticket-punching opportunities to move on to another job in another company, and lots of perks (saunas, free lunches, leave policies to pursue personal enrichment, etc.) But few of the sum-ups of these companies by employees remark on the ease of doing their work and none talk of improvement. My view is that these companies are running backwards: they can pursue exciting new ventures, pay competitive salaries including stock options, and offer perks because they have established a strong position in a particular market, not because their employees enjoy their work or do it well. And when their protected niche disappears – think Whole Foods – the decline can be quite dramatic.

So, if you are in a senior leadership position, what you do to become a lean employer that is more than nice and nice to work for? I suggest starting with the formula in The Work of Management by Jim Lancaster (launched at last year’s LEI Summit): Introduce daily management across your organization at all levels to create basic stability. Once this is in place you will have a stable platform for hoshin planning to identify and tackle your biggest problems and opportunities. And you will also have a stable platform for sustainable kaizen, beginning with the big problems and opportunities identified by hoshin planning.

As you make progress, change your stance toward your people. Introduce what I call “social heijunka” to stabilize their lives with predictable schedules, full-time work for those who seek it, and steady work in downturns and disruptions. (Remember to build cash reserves for this purpose!) Hire employees early in their careers and promote from within. Pay your employees more for jobs that superficially sound the same as those at normal employers, a stance you can afford because your employees are not only doing the work but constantly solving problems to maintain stability (and reduce the costs of waste) and constantly improving the work (to eliminate more waste and add more value for the customer.)

Stated another way, the lean employer strives to protect and retain employees because creating ever more value for customers with ever less waste (the definition of “lean”) is a long-term team sport. It can only work when long-term employees are learning together how to do better: Cycles of learning over extended periods through daily management, hoshin and sustainable kaizen. Gig economies full of short-term contractors rather than employees may sound nice to employers – “no obligations” – and to ex-employees as well – “no commitments” – but they can’t improve. They just shuffle people from one job and company to another.

I’ve been assuming, dear reader, that you are an employer. But it’s much more likely that you are an employee or an advisor to an employer (coach, sensei, guide, etc.) So how can you help your employer or client become a lean employer? By asking some simple questions at whatever level you are working: Why are our processes so unstable? Why can’t we sustain improvement? Is it because we have high turnover and no employee engagement? Why do we have high turnover and low engagement? This conversation is not open ended. It leads to a discussion of the social basis for good work and takes you far beyond the discussion of lean tools that probably can’t achieve sustainable results at the normal employer. Maybe you can even introduce the concept of the lean employer.

Whether you are an owner or CEO, or an employee or coach, I hope you will strive to create a virtuous lean spiral in which the lean employer makes work more engaging for its employees (who do the work and improve the work while eliminating struggles with the work) who become steadily more productive. This permits employers to pay employees more and protect them from the gyrations of the world outside the organization. In turn, this encourages employees to stay and even to become “loyal” to employers. And this increases the rate of learning and improvement in the next turn of the virtuous spiral.

These are the lean employers that I hope we all want to create and lead and the lean employers we want to work for. Perhaps more important these are the lean employers who can help create the stable, prosperous society in which we all want to live.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

CASE STUDY – In a Brazilian insurance company, a team worked hard to streamline the revision of dental claims – a great example of Lean Thinking in an administrative process.

FEATURE - We often hear that lean is a fundamentally different approach, but what does this really mean? The authors reflect on how lean challenges and debunks our assumptions on how to run a firm, which might also explain why it meets such resistance.

RESEARCH - In the last 10 years lean has made its way in many hospitals and healthcare systems, often with impressive results. Professor Dan Jones looks back at the lessons learned throughout the decade.

FEATURE - Lean discipline strengthened maintenance quality at Vale Indonesia’s nickel smelter by developing leadership, enabling early detection, and improving furnace reliability.