Building a learning hospital

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – At GHU Paris, leadership pairs strategy with gemba visits, 5C problem-solving, and cross-functional learning to create a resilient, people-centered improvement culture in psychiatric care.

Words: Catherine Chabiron

Today, I am visiting Sainte Anne Hospital in Paris. Showing me around is Guillaume Couillard, who oversees GHU Paris Psychiatrie & Neurosciences (which includes Sainte Anne) and co-authored L’Hôpital Apprenant (The Learning Hospital) with Michael Ballé and Anne Lise Seltzer. Alongside him is Louise Manteau, who leads the kaizen office.

A COMPLEX WORKING ENVIRONMENT

Guillaume and Louise immediately share some numbers with me. GHU, I learn, manages 60,000 patients in 170 structures across Paris and its suburbs, mainly dealing with patients suffering from psychiatric disorders – a complex and often misunderstood area of care. The organization employs 5,600, 600 of whom are doctors. Ambulatory treatment represents 85% of the work, but the hospital also manages nearly 2,000 beds.

Hospitals, as explained in L’Hôpital Apprenant, must constantly navigate tensions between administrative constraints, nursing requirements, and medical decisions. Psychiatric hospitals face an additional challenge: they rely on fixed annual budgets from the government and are often depicted in the media as the neglected corner of France’s healthcare system. As if that were not enough, working in a psychiatric hospital doesn’t always match a nurse’s career expectations, making it hard to attract talent. All this makes for a complicated situation.

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT TO ADDRESS COMPLEXITY

Guillaume took over as MD of GHU in September 2020. By that time, he had successfully experimented with continuous improvement, first in Nancy and later in Lyon. When he moved to Paris, he knew that local experiments and occasional training activities would not be enough to bring change to a highly complex group with many stakeholders. He had to try and establish a continuous improvement culture from day one. That, of course, is easier said than done.

He took three critical decisions:

- Framing the overall mission of the hospital: “Take better decisions for our patients, support our nursing staff.”

- Launching a broad program of individual learning through problem solving.

- And relentlessly walking the gemba himself to reinforce the above.

STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT AT THE TOP

With all this information swirling in my head, we head to the organization’s main Obeya downstairs. This is where Guillaume articulates his strategy for GHU (take better care of both patients and nursing staff) and holds one-to-one meetings with each of his direct reports.

We look at the KPIs monitoring unavailable beds, the time patients must wait before a first appointment, the time spent in nursing areas, staff satisfaction level (70% positive ratings), and so on. But Guillaume is closely reviewing regular staffing reports to identify units facing severe nursing shortages – making sure they get attention and support.

The rest of the Obeya reflects a simple, but efficient approach. Each of Guillaume’s direct reports – whether they are in charge of Nursing, IT or Maintenance – regularly updates, by hand, a board with their target and the changes they are managing (ongoing, past, or simply contemplated). Why focus on changes? Given the above-mentioned tension between the three logics of administrative staff, nursing and physicians, Guillaume is painfully aware that one person’s solution is bound to become another person’s problem. The changes are consequently discussed on a one-to-one basis (to understand and challenge) but also in the COMEX, where colleagues will possibly question them or point out any risks. “Discussions on changes are a great opportunity to create alignment and refocus on the strategy,” Guillaume says.

The COMEX, he explains, has a fully standardized agenda to avoid moving away from the mission. They start with a patient story (a claim, an issue, an incident). Then one of the Directors will recount his or her latest gemba. As mentioned before, they take turns sharing any current or upcoming changes in their area. They then spend time on learnings resulting from a kaizen. By the time they reach the final agenda items, the essential work has already been discussed.

Guillaume says that he stands his ground on the mission and the “how”, but that he is more flexible with the adoption speed. He has lately promoted Functional Analysis in his one-to-one discussions. “I want them to reflect on their role and impact. I have them think about their external and internal customers’ needs, to determine the functions their department must develop,” he explains.

After the Obeya, I join Louise to visit the other Departments at Sainte Anne Hospital. She wants to show me how they develop their own obeya to connect with the central one. Indeed, in Nursing, we find the same explicit mission around patients, and the same boards monitoring changes. But critically, we now see how the mission translates into the specific context of the Nursing Department. Junior management support is one such example, while the reflection on temporary workers, which cannot be addressed by Nursing alone, will be escalated to a cross-functional Task Force . The routine of one-to-one discussions and collective challenges is the same, the overall mission towards patients unchanged.

We then move to Purchasing & Logistics, where the mission is more focused on supporting the nursing staff (making their work easier so they can in turn make better decisions for their patients). But there is more.

PDCA IN FIVE COLUMNS EVERYWHERE

Cristina is the Manager of Purchasing & Logistics. Standing by the board, she eagerly explains the second element of the three-fold cultural transformation initiated by Guillaume: continuous learning at all levels through a simple PDCA in five columns – date, problem, cause, countermeasure, impact. She shows us, for example, how adjusting tools and routines to each specific type of purchasing enabled them to significantly reduce the time between a purchasing request and its receipt.

Ysatis, another member of the Purchasing team, is struggling with late payments and broken information flows. Her 5Cs, as they are now called within the hospital, aim to reduce the time spent by nursing on administrative tasks and to convince key suppliers to stay.

Back with Guillaume, I am now visiting a Medical and Psychological Centre. He constantly visits all the hospitals in the group, at the pace of one or two per week. I am impressed by the number of people attending this visit: doctors, nursing staff, psychologists. Proof that this continuous improvement culture is taking root, I’d say.

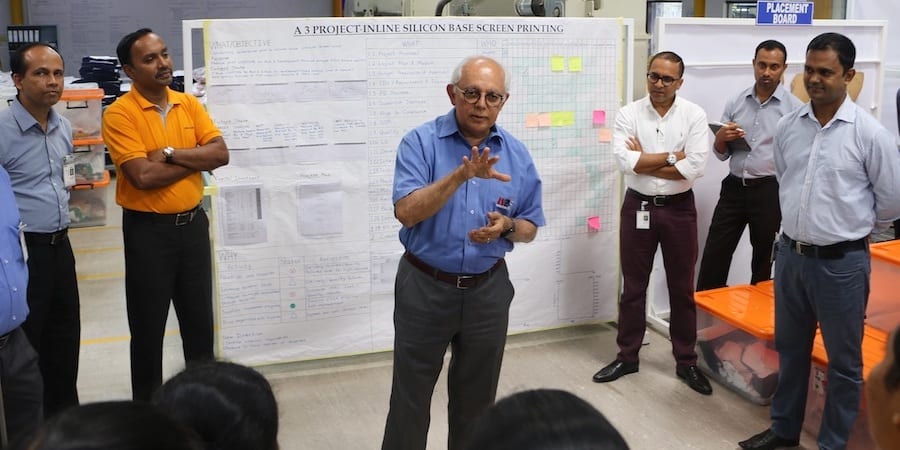

I am witnessing here – last, but certainly not least – the third element of Guillaume’s initial strategy for cultural change: genchi genbutsu (go and see for yourself) during regular visits to the gemba. I watch him ask questions about patients, look at the admission process, challenge the team on delays, or on roles and responsibilities. The discussions are informal, but serious. They take place standing up in front of a board, sometimes in the nursing ward. He also takes advantage of an upcoming change in software to have the staff commit to preparation, risk management, and problem solving.

“When do you plan to meet around a 5C for a learning time?” Guillaume insists with team, eager to get them to commit to a date and a regular cadence for the learning sessions. After the visit, he confirms that he insists on a 5C takt time because it generates commitment. “It is scheduled every week, not just when you can find time. When the takt time is adopted, improvement speeds up,” he tells me.

He also takes the time to explain a 5C process to the team: the simple example of a dehydrated patient in a waiting room is used to show how to select the problem they want to discuss, confirm the cause(s), look at the countermeasures that were implemented, and learn from it. “We do not use 5C to actually solve the problem,” Louise will explain later. “But rather to discuss how it was solved, after the fact, and to learn from it.”

RELENTLESS GENCHI GENBUTSU PROVIDES ENERGY AND FOCUS

Guillaume has managed to perform 350 such gemba visits in three and a half years. He believes he has between 100 to 150 gemba locations to see, including support functions. He is careful not to burden the teams (or himself) with action plans: the visit’s goal is to provide a space for reflection and an opportunity to share challenges and real conditions for patients and staff.

When I challenge him on whether he has a standard approach for gemba visits, Guillaume pauses for a moment to reflect. “I include a time for recognition,” he then tells me. It is important to listen and spend time with people confronted with, for example, difficult patients or limited resources. He never spends less than an hour on any visit. “It’s really an opportunity to face reality and possibly challenge the COMEX as a result. But it’s also a time to train. I have people work on the next step, the next improvement.”

He mulls it over some time. “I may sometimes challenge them hard to focus them back onto our mission – the patients. But I find that using tools, such as a 5C or a 5S, as a medium transforms the conversation: we’re no longer on the who, rather on the how and the why,” he says.

FROM INDIVIDUAL LEARNING TO COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE

We’re back in Guillaume’s office, together with Louise. She has also been playing a key role in driving the latest wave of cultural change: 5C or 5S are ideal to discuss issues over which you have control, but an hospital is full of cross-functional problems that will require the expertise and availability of other departments, and probably a bit of negotiation and some trade-offs. Guillaume and Louise have consequently promoted six-point kaizen tools, hoshin templates, communities of practice, and task forces to cover the entire spectrum of the needs.

“If we had started with six-point kaizen, complex issues, and A3s, everything would have quickly gone into project mode,” Guillaume reflects. “I really wanted them to get acquainted with problem solving within their scope, so that they would routinely adopt the same mental frame when moving to more complex issues.”

Task forces come together around a topic, sometimes for several years. They meet every week or two and have an ongoing discussion about structural issues, such as attracting and retaining nurses, funding/sponsorship for research, or sustainable development. “Kaizen is ineffective for a topic of that magnitude: too many factors are beyond our control,” Guillaume adds. A Task force will dissect the problem, identify possible levers that can be actioned, take new regulations into account, propose tests, monitor them, learn, drive innovation.

We look at some numbers: one unit managed a two-thirds decrease in the number of unavailable beds in one year; there have been noticeable increases in research funding and a reduction in the use of resource (18% less gas consumption in two years and 13% less water consumption in one year); recruitment, too, has seen some successes. When no KPI is immediately available, the Task Force will count the number of successful improvement.

WHO TALKS TO WHOM: KEY KNOWLEDGE IN COMPLEX ORGANISATIONS

I turn to Louise to ask about Communities of Practice (CoP). “We have different locations, hence different CoPs. If you take the continuous improvement CoPs, I usually lead the discussions on ongoing changes that may affect performance, then we have someone show an example of 5C in action. We may also include a bit of theory on continuous improvement if there is time,” she tells me. An essential piece of savoir-faire in complex organisations is to know whom to talk to, in any given situation. The underlying objective of CoPs is to get to know each other: participants include office clerks, healthcare managers, nurses and administrative staff. If necessary, the CoP can invite an expert on a specific topic. Some problems discussed in the CoP can also be escalated to a Task Force.

Guillaume chuckles. “We didn’t build it as a CoP, but this who-talks-to-whom is typically what we have achieved with support functions,” he explains. Locations outside Sainte Anne, where all support functions are concentrated, complained that support was never sufficiently available to them. Guillaume encouraged the IT, Maintenance and Logistics support functions to start holding a regular meeting in these locations. This was a win-win situation: meetings have now become an essential routine, and old issues have been resolved. They have gone from “no one ever listens to us” to “I know who to talk to for this type of problem”.

Focus on patients, and on nursing staff. Give each actor the time to explore. Introduce a takt to pace and drive commitment. Provide tools adapted to the magnitude of the problems. Train and explain, again and again. Encourage the creation of communities of practice. And relentlessly go and see. Indeed, Guillaume and his team show us the way to a learning hospital.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – Prior to his talk at this year’s Lean Transformation Summit, the CEO of a large apparel manufacturer tells us about the company’s lean journey, and its impact on Sri Lankan society.

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – Somfy’s R&D department is applying Lean Thinking to close knowledge gaps, improve collaboration, and boost innovation and technical competence.

FEATURE – At Nijhuis Mitech, management is so involved that the owner can often be seen at the gemba running experiments with people. The transformation that ensued is helping the firm become more efficient and stay competitive.

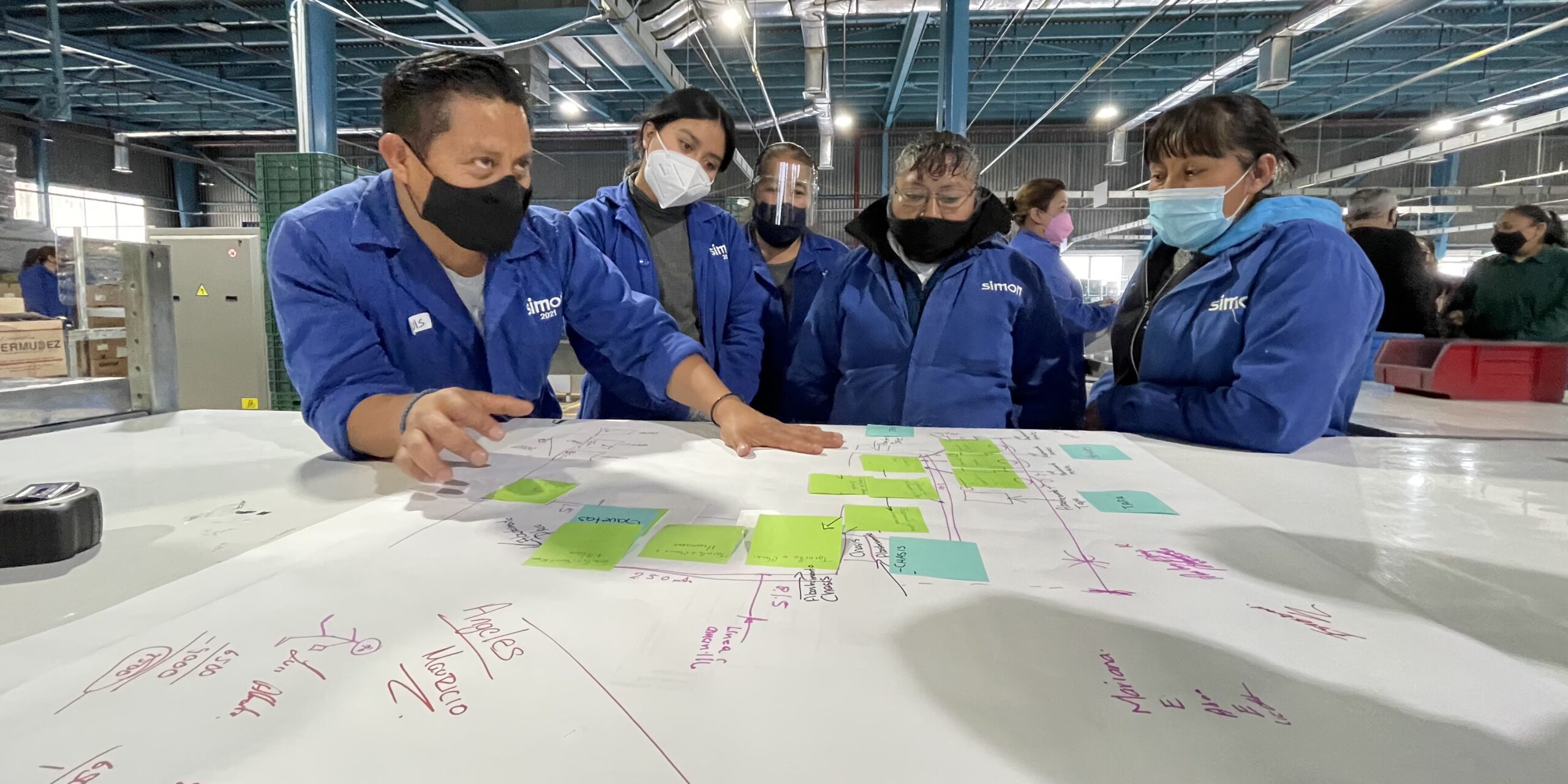

CASE STUDY – Starting in January this year, the Mexican plant of this manufacturer of lighting and electrical solutions has initiated a lean transformation that has already led to impressive results in terms of productivity.

Read more

FEATURE – Our coverage of the Covid-19 emergency continues with an article discussing how lean healthcare principles can support and protect the professionals at the front line of this war.

FEATURE – In a bid to find inspiration and new ideas to achieve excellent outcomes in patient safety, a group from a Boston hospital flew to Orlando to visit JetBlue Airways.

FEATURE – Hospitals are often part of larger healthcare systems, which makes it critical to learn how to bring lean to such diverse and complex environments. We hear from a large hospital group in Ireland.

VIDEO - The CEO of a cancer center in Brazil gives us a tour of the their obeya room, taking us through their strategy deployment and explaining how it supports their mission of reducing the burden of cancer.