Michael Ballé reflects on how lean really works

FEATURE – Continuously studying the challenges we meet and the responses we devise, lean management gives us endless opportunities to learn. The author goes back to basics, reflecting on some core lean premises

Words: Michael Ballé, author, executives coach and co-founder of Institut Lean France

Your reactions to my piece What Really Happens on a Gemba Walk have really made me think of a deeper question: How does lean work?

Besides the techniques, lean thinking is based on four core premises: 1) the passion for what we do through delivering more value, 2) the discipline of learning how to respond to our main challenges, 3) the curiosity to “learn to learn” (discovering the topics we need to learn), self-train to improve our responses to our main challenges (or discover responses to new challenges), and 4) a commitment to building stronger relationships.

LOVE WHAT YOU DO (AND WHO YOU DO IT WITH)

In lean terms, the passion for what we do expresses itself in the form of a relentless drive to deliver more value – to customers, to partners, to ourselves. It is a unique aspect of lean thinking that we assume that we’re already pretty good at what we do, but often have misconceptions of the real situation – which leads to wasteful behaviors, reactions and activities. Because we cling equally dearly to all our beliefs (after all, if we didn’t, we’d change them), these misconceptions in our thinking are hard to surface, which is why we commit to challenging ourselves on delivering more value every day. We strive to discover where value evaporates in wasted energy.

This commitment to offering customers more value has two very beneficial effects. First, it spurs you to compete better, as most competitors are busy optimizing what they already do (often pissing off their customers in the process). Aggressively seeking to deliver more value clearly distinguishes you from the rest. Secondly, and not less important, this daily commitment to seeking to do things better also keeps the love for what you do alive – work remains fun, you surround yourself with more interesting and passionate people, and you’re supported by a sense of purpose, as well as interest generated by the discovery of new insights into the basics of your work. Seeking daily improvement is the greatest source of love for what you do.

THE DISCIPLINE TO REFLECT

A large part of any job is facing routine, typical problems, and responding habitually. The difference between doing a good job and an average one is the daily discipline of responding the best way we know how, as opposed to being satisfied with the first action that makes the problem go away. This requires discipline, because in any routine job the temptation to cut corners is always there (when conditions warrant breaking the rules, it’s even necessary), but one cut corner leads to another, and then another, until you find yourself with poor performance and lower value.

Discipline in the lean sense is not about rigidly enforcing rules or “best practices”, but having the personal will to take a step back, think about what our best response should have been, and compare it to what we actually did and why. Of course, no one can be expected to perform the best way at all times, especially when facing changing circumstances. Rigid “discipline” in applying rules regardless of conditions is the best way to kill any passion for the job by forcing people to take actions they can see are inappropriate.

This mental discipline is a further source of love and understanding for what we do, as well as greater tolerance for others’ mistakes, because we can better see what brought them to react the way they did. As the saying goes, before criticizing someone, walk a mile in their shoes.

LEARNING TO SELF-TRAIN

The difficulty with learning is not just in the process of acquiring new knowledge – everyone loves to learn more about what they already know – but discovering the topics one ought to learn (and often don’t want to face). The unique role of a lean sensei is to give you exercises to do in practice in your job in order to either:

- Succeed easily and move on to the next step;

- Fail to do the exercise, figure out the difficulty encountered, and look for the deeper problem.

The sensei is neither a teacher nor a coach – he or she is a more experienced person whose role is to show you where to look by giving you concrete exercises to practice in your own workplace. The learning, however, is your own responsibility, so that the skill lean thinking develops is literally self-training. The sensei is not a coach in the sense that he or she will not be there to push you or cajole you to learn. Their job is to point you in the right direction through concrete exercises (think “wax on, wax off” in the legendary Karate Kid movie) or by example (Mr. Miyagi practicing Crane technique on the beach); yours is to learn.

Self-training is the hardest and most rewarding part of lean thinking. It both gives you an edge over your competitors, transforming it into long-term advantage, and deepens your understanding of your job and the market conditions you do it in. Self-training develops both deeper thinking and concrete hands-on skills. It liberates you to study your own habitual responses and change them to become increasingly autonomous and self-reliant.

Self-training is also one of the greatest areas for misunderstandings, as the sensei base the learning exercises they give you on the fabled Toyota Production System:

- Delivering more safety, quality, lead-time, flexibility, cost, energy performance and morale;

- Reducing lead-time through greater flexibility and coordination;

- Stopping at every defect, and helping people to solve problems before moving on;

- Engaging teams in owning and improving their own ways to work and workplace;

- Developing mutual trust between workers and management by supporting friendly, self-reliant teams and fighting to give them the conditions to do great work.

It’s easy to mistake the lean system for a toolbox: apply this tool to this problem and things will automatically improve. It’s equally easy to fall into the opposite extreme and think that coaching doesn’t require the constraints of the TPS (or cherry-picking your favorite aspect of the system as the only you need – hint: it’s a system!). In truth, the system is a concrete, hands-on theory of improvement that helps the sensei to find which exercise will make you progress right now (just as the sensei will progress in his or her understanding of the system itself).

BUILDING STRONGER RELATIONSHIPS

No one works – or succeeds – alone. We’re all part of a chain of value, from the individual craftsman to society at large. Self-training is both about developing one’s own expertise and the wisdom of better working with others across boundaries. Getting the job done means building the right alliances, and, ultimately, having the wisdom of turning enemies into friends. Because lean thinking is a study of challenges and responses, it’s really a study of how we define challenges together and how we build responses together, according to each person’s unique perspective, interests and special insights. To a large extent, lean thinking is not just a science of improvement, but also a science of building stronger teams.

To tell it as it is, the exercises the sensei ask you to do are also leadership tests. They are concrete challenges to have a team try something different in the way they work, and then observe, discuss and reflect on what happened as a result, which means being able to lead others through the change. These are not puzzles you can resolve at your desk or by yourself on a piece of paper. For instance, the very simple challenge of having a team “5S” their own area (organize it to make work more intuitive and maintain the discipline of keeping it this way) can easily turn into a practical test of your ability to grow mutual help and shared responsibility relationships.

The strength of these relationships is what makes lean so flexible in the end. The ability to work together without central control, through shared purpose, win-win interests and side-by-side orientation (which involves common reference points) is precisely what gives a lean supply chain its potential to respond to change and challenges. The exercises outlined by the sensei are rarely simply about individual virtuosity. Kaizen is a team-building activity.

Lean is not for everyone. Not because it’s particularly mysterious or complicated, but because it requires four deep commitments: to face our challenges in order to find more value to deliver; to be disciplined in our responses, both with routine problems and new, unexpected ones; to self-train and learn what we have to learn in order to succeed at responding to our challenges (which, in lean, men ans accepting to follow a sensei where and when he or she points the way); and to do it all together.

Lean is a self-development method, not an organizational framework. And yes, we all have good days and bad days. Sometimes we think the work is good enough (why can’t customers see how hard I work and how difficult it is, for a change?). Sometimes we’re under pressure to cut corners, and then to cover up cutting corners. Sometimes, we simply can’t be bothered to challenge habits. And that’s ok. The point of a lean system is that it remains there for us when we want to get back on the bike and keep climbing up the learning curve – no matter how often we fall. The deeper learning is always right behind the lesson we currently struggle with. Which is also what makes it endlessly fun.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

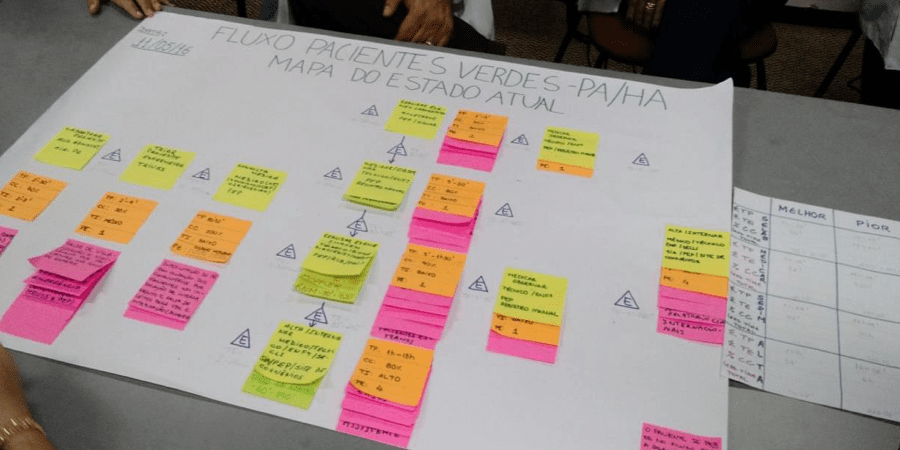

FEATURE – Long waiting times are bad for both patients and hospitals, but when we talk about heart attacks reducing them becomes a moral imperative. Here’s how Hospital Aliança in Brazil is doing it.

FEATURE – Last year, the Lean Global Network entered a partnership with the Singapore Institute of Technology to bring lean capabilities to local SMEs. Along the way, we discovered an alternative approach to academic teaching.

INTERVIEW – We have come to dread having to interact with customer support representatives, and quite rightly so. Basecamp has made it a mission to bring humanity back to this interaction.

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – In this month’s column, Jim shares an insightful analysis of the trends and dynamics of today’s automotive industry and looks at the opportunity that lean has to facilitate its next transformation.