A step-by-step guide to leadership and team lean development

FEATURE – When middle managers are stressed and overworked, there is no time left for them to improve. Changing the interaction between leaders and teams, using lean principles and empowering people, can truly ignite your transformation.

Words: Wiebe Nijdam, former Director, Lean Management Instituut

Lean can be frustrating at times. It is all too common to see organizations draw their value stream maps, coach their people, diligently apply their lean tools and yet fail to turn around. It is hard to accept that results are not coming when we think we are doing everything the way we are supposed to.

We at Lean Management Instituut have been looking into this to try to identify the missing link. While there are a million reasons a lean transformation can fail to produce the desired results, one element seems to come back over and over again: the interaction between the leader and the team the leader works with.

Let’s take a look at a typical initial situation in an organization that is struggling to progress on its lean journey.

On one side, we have a leader controlling a group of individuals and trying to ensure they do things the way they should. The leader is constantly busy fighting fires and checking what people are doing, which leaves her with no time to improve. In the (false) hope to control the situation, leaders tend to develop one-to-one relationships with a few key people reporting directly to them.

On the other side, we have a group of people, with one person normally standing out: she has worked for the company for 30 years; she is great at what she does; she is the specialist, the hero. The other two people are new to the organization and quite inexperienced. What happens when they try to work together as a group is that the hero tends to have the answers and monopolize the decision-making process. However, when the hero is always right, the group mechanism is stuck and the organization is stuck with it. It just can’t move to the next level. This lack of balance will not go away until we start looking at the other members of the group (we can’t talk about a team, yet) and make an effort to develop their capabilities as well.

So, what can be done to get out of this static situation? How can we develop the skills of our leaders on one side, and of our teams on the other?

As I will explain, I see four main transitions taking place in this approach to development, two at leader’s level and two at team’s level. We should adopt this system if we want to transform the way our leadership interacts with our teams.

THE FIRST TRANSITION

As it is often the case in lean transformations, capability development is the answer to our predicament. We want everyone in our team to become as good as the hero – the prerequisite to start improving – and our leadership team to change the way it works with people.

Following the initial assessment of the situation, we are ready to tackle the problems with our current state (namely, the dynamics in the group and the failure of the leader to do anything more than “trying to survive the day”) that we have unearthed.

On the team side, what we want to do is even out the skills sets of the different members. A great tool to support people development is the skills matrix: it allows us to break down a process into the individual actions that must be carried out, and to understand who within our group can perform each of them.

A skills matrix considers five levels of capability: I don’t know how to do something; I can do it generally; I can do it well; I am certified as capable of doing it; and I can teach others to do it. Let’s imagine working in a manufacturing environment and let’s take the action of cutting as an example (and three workers – Mary Li, Jerry and Sharron): Mary Li can teach others to perform the cutting and Jerry is certified, while Sharron is completely inexperienced in that. The idea here is to follow the 3:1 = 1:3 rule: we want to get to a point where every person can do three tasks and every task can be done by three people.

It is the role of the leader to use the matrix to find what the key processes are and determine who needs development, in what areas they need it and who is best placed to teach them those skills. Once there is clarity over that, the leader can then coach the members of the group to facilitate learning: for example, he will talk to Sharron and encourage her to work with Mary to learn from her.

The matrix is an incredibly powerful tool, yet it is somehow underestimated. By asking people to work together and developing those who need development we start to turn the group into a team: people grow closer and things become more balanced as it becomes clear that everyone has something to contribute and to teach others. The goal is to develop a team of experts, rather than having only one hero in a group. Additionally, team members become responsible for the results of the process – they start to own them.

As a leader you don’t want to rely on one person only, but to coach and develop a team, but this is only possible if you are committed to giving up control and make people accountable (David Mann’s lessons on lean culture come to mind here).

Changing as a leader is easier said than done, you might say. And you are right. Thankfully, we have lean on our side.

Through visual management you can set clear targets and keep track of them, while challenging people to help you reach your most important KPIs. Visualizing processes helps you to see right away when there is a gap, so that the team knows immediately what needs to be tackled.

Kata coaching can then help us to ask the right questions and start useful conversations that help us to understand the reasons of deviation. I recommend carrying out the kata coaching in front of your boards, because there is no escape from the data there. Sadly, most organizations still engage in what I call “wild kata”: they read about kata, go to the shop floor and ask people what the target condition is. In this scenario, however, people don’t know what problems need to be solved. It is necessary to clarify what standards we are going to try to improve first, which makes the synergy between visual management, kata coaching and the skills matrix critical.

On the leader’s side, the first transition therefore entails developing the leader’s coaching skills and using visual management to flag up problems. This puts you in a position where you can support your team’s transition, using a skills matrix as a team development tool.

While leadership works on refining its coaching skills and on making visual management an increasingly big part of the life of the organization, the team can start focusing on the creation of standards and on aligning everybody’s work to them.

Once we have broken down processes into tasks and we have a standard for each of the essential tasks (which is by definition teachable), we can move on to TWI – Training Within Industry – and its job instructions, job relations and job methods. These are valuable tools that come in handy whenever we are trying to understand the specifics of the work, solve problems in the way people relate to one another, or figure out how we should behave.

There is a direct link between TWI and the five characteristics of a good supervisor according to Toyota, as explained to us by Art Smalley:

- Knowledge of work (how we do things)

- Knowledge of responsibilities (what we need to do by when)

- Skills to lead and motivate (why we do things this way)

- Skills to improve methods (how we can do this better)

- Skills to teach (how to pass our skills along to others)

For each of the three skills, we have a TWI standard program:

- Job relations help us to become better leaders

- Job instructions helps us to teach others

- Job methods helps us find ways to improve

As we develop people’s capabilities in these three critical domains (developing our ability to lead, teaching others and improving), it starts to get easier for us to improve as an organization. We no longer depend on an individual doing something different, but rely on a standard that we can teach and enhance over time. Additionally, knowledge is shared within the group and the team members can now perform a wider range of tasks (which makes job rotation possible) without risking being overburdened.

Critically, the leader starts to interact more with the team as individuals take on more responsibility for their processes. In the meantime, the process becomes more stable due to the new standards.

The first transition on the team’s side is therefore to stabilize the process, by standardizing tasks and teaching every team member how to perform them – following the 3:1 = 1:3 rule.

MOVING ON – THE SECOND TRANSITION

The second critical transition in this shift is the introduction of leader standard work on the leader’s side and an increased focus on daily accountability, problem solving and kaizen skills on the team’s side.

Until now, we have brought people who were at different levels of professional development to the same level, thus creating a team and getting it to focus on a common goal. This is the time we can really start to make things better.

But what about the leader? What are the standard behaviors and actions she should commit to in order to further enable the organization? Of course, we have a fixed sequence of gemba walks, problem solving on the shop floor, and so on, but there is more to it. It is necessary to develop the leader’s own skills as well.

This starts with truly understanding the seven practices of leading with respect as brought to us by Michael Ballé.

A leader must be able to challenge her team and work with them towards sustained performance. This requires finding the time to improve every day, being able to translate strategy into practical goals for different levels of the organization, fostering a culture of problem solving, and creating a daily accountability system.

In our initial situation, the leader didn’t have time for any of this. She was too busy fighting fires and ensuring the process could run. Now checking whether the process is running properly takes very little time, which means the leader is finally able to focus on real root-cause analysis and on taking initiatives to bring the organization to the next level.

Improving the organization as whole means to understand how the process runs end to end and how it functions in other areas. This is the only way to adopt a value stream view. And what better way to understand others than walking in their shoes for a while? I am not suggesting a skills matrix for leaders, but jobs rotation can work as well at their level as it does at team level. Send the manufacturing manager to purchasing, or the purchasing manager to finance, for example, and you are guaranteed to broaden their view of the organization and help it to move past silos once and for all.

In the meantime, team members are fully skilled to perform any daily task. Job rotation is fundamental here as well, as it spreads knowledge and understanding of different parts of the job, improves relationships in the group, and enables productive discussion on potential improvements. Planning has become stable and as a result daily tasks are performed on time, which leaves plenty of time for improvement.

CONCLUSION

To recap, how do we develop our teams and leadership to support the necessary changes in our organization? Here is the sequence of actions (which include the four transitions we have discussed above):

- Enable visual management to spot deviation

- Use A3 thinking to address performance gaps and solve issues in our processes

- Develop kata coaching skills

- Create leaders standard work

- Make time for real improvement using the three skills of a leader (lead, improve, and teach)

- Learn to translate organizational goals into practical process goals through practical strategy deployment

- Start the necessary improvements from a value stream, system-wide perspective.

We have been working hard to create the same dynamics and structure at every level of the organization, from the boardroom to the shop floor. This provides our organization with a common language that we can then leverage to take further improvement steps towards the completion (and sustainment) of our turnaround.

Creating visibility over what others do is equally important at all levels of the organization, as is working as a team and taking time to analyze the root-causes of problems. The system described in this article is a real enabler of change: it facilitates vertical communication and alignment (strategy deployment - for which I wrote a guide here on Planet Lean) as well as the adoption of a system-wide view of the organization (value stream).

The synergy between leader and teams is what fuels our lean transformations. The potential of this approach is something leaders tend to oversee; yet, 20 years of experience facilitating transformations has showed me it truly is the improvement engine of your organization. Assembling this engine and making it possible for people to work with it is up to you as a leader – it is my hope that this article will help you get there.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

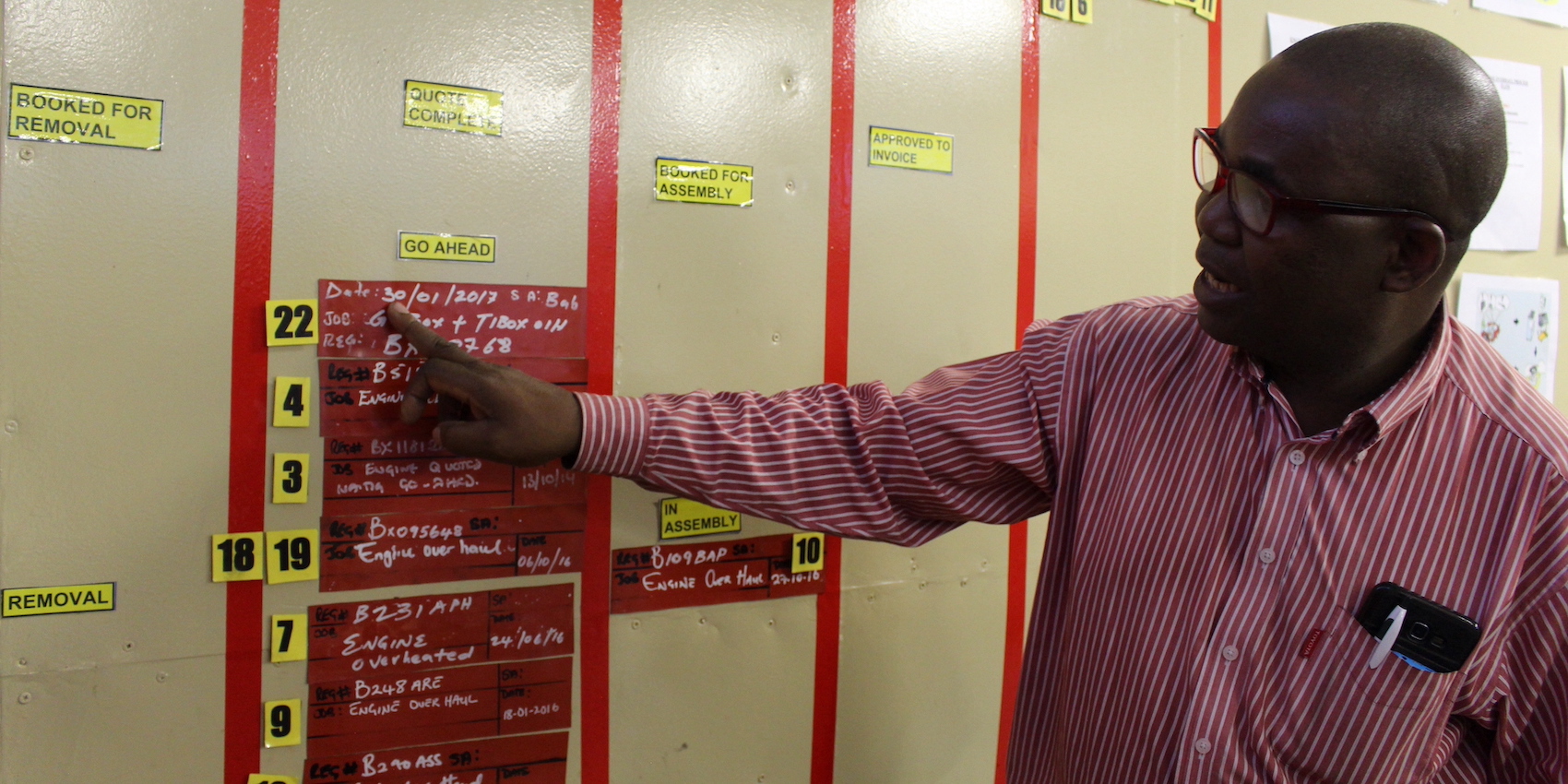

FEATURE – Sharon Visser shares her leader’s standard work from when she ran the Ngami car dealership and encourages us to use what we see at gemba to shape our own.

THE TOOLS CORNER – For the second article in our new series, the author offers a guide to the origins and use of one of lean's most important tools: SMED.

CASE STUDY - The Italian branch of Tokheim services about 3,000 gas stations in the central and northern parts of Italy. The general manager shares the story of how lean thinking changed everything, for the better.

FEATURE – The Covid-19 pandemic has reminded us all that the nature of the work has changed forever. The author discusses remote work and how Lean Thinking can help you make the most of it.