The power of process

FEATURE – The introduction of a new process can be disruptive to an organization’s improvement efforts. But what if the process were designed to be lean from the start?

Words: Matt Zayko and Eric Ethington

Certain experiences continue to inspire for years on end. In our case, it was our learnings from over two decades ago – that still resonate with us as we study Lean Thinking and try to help practitioners to uncover its many layers.

It was the spring of 2002 and our team, at a major manufacturing organization, had achieved a key milestone in the transformation of a legacy production operation to a lean production system over many months. This cross-functional team, with key involvement of the front line, gained superior results in safety, ergonomics, quality, delivery, employee engagement, and waste reduction that resulted in productivity gains of 67%. This led to a completely new vision for the facility layout, which allowed the team to free up valuable floor space that was used for insourcing lower-volume value streams from a remote location.

But the enthusiasm and energy that were growing were soon brought to a halt when a new process for a next-generation product began to get installed. Although designed by well-intentioned engineers, this new process was too familiar in an unfortunate way – it was just like the legacy processes we had “kaizen-ed” through incredibly hard work and long hours for months.

The team was deflated that the new process did not embed Lean Thinking into it. We still believed that we could quickly do kaizen on this new process, but since it was so important to our biggest customer and already behind schedule with many troubling issues, this proved impossible. Instead of continuing our efforts to do kaizen on areas in the plant, all of the resources were shifted to the new process to simply make the ramp-up schedule and solve basic operational problems using suboptimal methods.

Sadly, the situation above is not unique and continues on even decades later. This scenario has been observed over and over in many organizations and across many industries. We have seen experienced lean leaders with a solid vision and a plan, whose efforts are derailed by the introduction of a new process. Teams are re-directed to get the new process working, and kaizen of other areas becomes the aspirational work the team will “get to” if they ever have time. This is so common that we become desensitized to it. It just becomes normal.

When we reflect deeply, we find there is a gap in understanding by those designing new processes. Sometimes the processing times and their relationship to customer demand (takt) are calculated, but frequently they are not. When we dig deeper and inquire into process expectations for yields, changeover times, motion paths, and balance options, the information becomes even murkier. The reality is that significant sums of money are spent on capital with a vague understanding of why. As stated before, this is normal.

Although this may seem overly negative, we are actually trying to help illustrate the opportunity that we all have in front of us. Most companies begin their lean experiments in operations. The work is typically easier to see than in business processes, as are the issues and wastes that get in the way of the value-adding steps. Similarly, gains can be quick – which also impacts the customer. Kaizen also creates, as our sensei wisely told us, real “evidence on the floor” of improvement.

These kaizen actions are important and necessary, but in the end, we started to ask many questions. How many of these kaizen activities are actually rework? Why do we dedicate technical resources designing new systems, only to always apply more unplanned resources to fix the systems? Why not design lean into the new process upfront? How do we break the rework cycle? In fact, it is our hypothesis that many kaizen activities are actually “touzen” activities – kaizen that should not have been necessary.

Many organizations have recognized this and have tried their version of lean process design following a formula. It may be an episodic 3P event, but these are typically too late for impactful benefit and do not feedback key learning upstream. Real, impactful lean process design goes well beyond pushing concepts and slogans into each situation. It needs to have a clear purpose, a scientific basis, and an adaptable framework because every situation starts from a unique initial state. Importantly, your lean process design framework must recognize the need for both technical and social aspects, as they are linked in order to sustain and improve any system.

In summary, many years of first-hand observation of the problem of reworking processes in manufacturing, healthcare, engineering, supply chains, and numerous other areas brought us to the realization that a practical book focused on the key lenses and the standard work of lean process creation could be helpful to organizations that desire to reach a new level of performance.

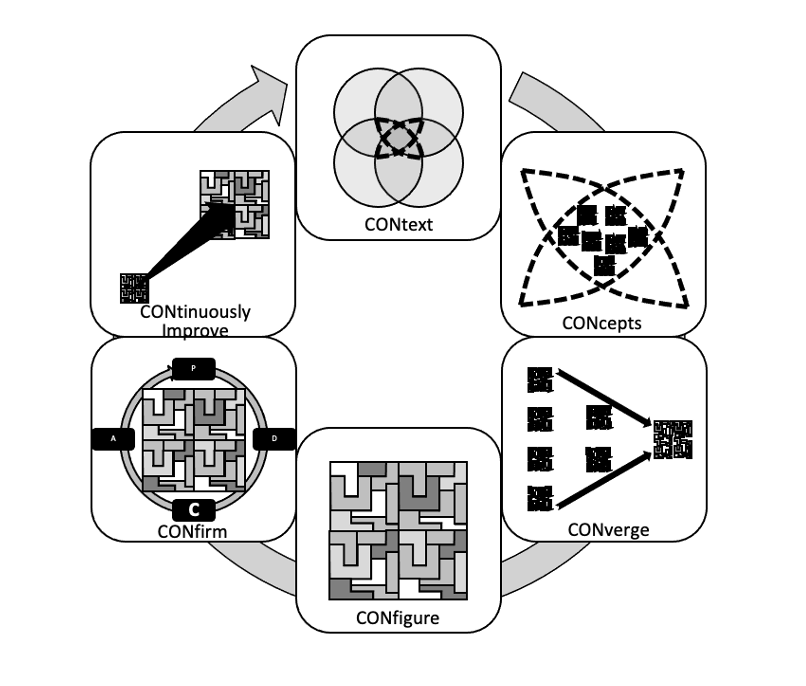

In The Power of Process (available now from major booksellers), we introduce the six key lenses for designing any new process, which is the 6CON model. The six CONs are:

- Context

- Concepts

- Converge

- Configure

- Confirm

- Continuously Improve

These lenses help process development teams to focus on the right learning at the right time, and are powerful when combined with a system architect to “conduct the orchestra”.

For more details, please visit www.thepowerofprocess.solutions

THE AUTHORS

Read more

GETTING TO KNOW US – It’s easy to over-complicate lean thinking. This month’s Lean Global Network interviewee tells us why we should always start with the work and the people doing it.

NOTES FROM THE (VIRTUAL) GEMBA – This small manufacturer is relying on Lean Thinking to keep the business running during the Covid-19 crisis, overcome the disruption in its supply chain, and even innovate.

OPINION – How many times, in the early stages of kaizen events, have you thought about giving up? Hang in there. As frustrating as they can be, they will also teach you a lot, says our Danish colleague.

CASE STUDY – UK law firm Weightmans has transformed its new legal case intake process using the Lean Transformation Framework, revolutionizing both operations and people development.