How a construction company survived the recession using lean

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – With a strong focus on quality and on solving problems once and for all, Paris Ouest Construction has managed to weather the storm of the recession, the author finds out during a gemba walk.

Words: Catherine Chabiron, lean coach and member of Institut Lean France

While industries like manufacturing and services are full of improvement stories here in France, there is one sector that seems rather indifferent to quality systems and lean management (even though it is marred by complexity and risks): house or office building. Search for literature and stories on quality management in constructionand you’ll be surprised by the poor return you get.

The reason for this is probably the fact that a building is a unique prototype – which can be refined as and if needed – while industrial production works on high volumes, and needs to focus on right first time to reduce the cost of poor quality.

Yes, construction is a different story. That’s why I was eager to discuss this topic with Jean Baptiste Bouthillon, CEO of Paris Ouest Construction, and visit some of his construction sites. Jean Baptiste is a firm believer in the power of lean thinking applied to construction – he spends 40% of his time walking around his sites, four each week – and the opportunity to go on a gemba walk with him was just too great for me to pass on.

Like its competitors, Paris Ouest Construction suffered a major setback since the economic crisis of 2008: it is a rather small company, with 260 employees (and 60 temporary workers). With the downturn, investment in buildings slowed down dramatically, even in Paris, and only now is business starting to pick up again.

So how did Paris Ouest Construction manage to overcome the crisis?

As Jean Baptiste put it, as we walked towards the first building site he wanted to show me, “We spend half of our lives at home, so we need quality and comfort there. And when we build something, we physically change the environment – and for a long time – so we’d better think ahead during the construction.” For example, we can only guarantee low energy consumption throughout the lifetime of a building if the quality of the construction work is top notch.

Jean Baptiste explained to me that he likes to think in terms of “quality at delivery”. But how to measure that? While automotive industry measures PPM (defects per million parts), the construction industry believes that five outstanding issues per flat delivered is a pretty decent score for a “prototype”. This led Jean Baptiste and his team to wonder how customer expectations on quality should be defined. Clearly, this is not easy, with the bid awarded by an investor, the specifications and control being the prerogative of an architect chosen by that investor, the running of the finished building often being a third party’s responsibility, not to mention the people who will live in the flats or work in the offices (they will all have a different definition of quality). We are talking about a very complex system here.

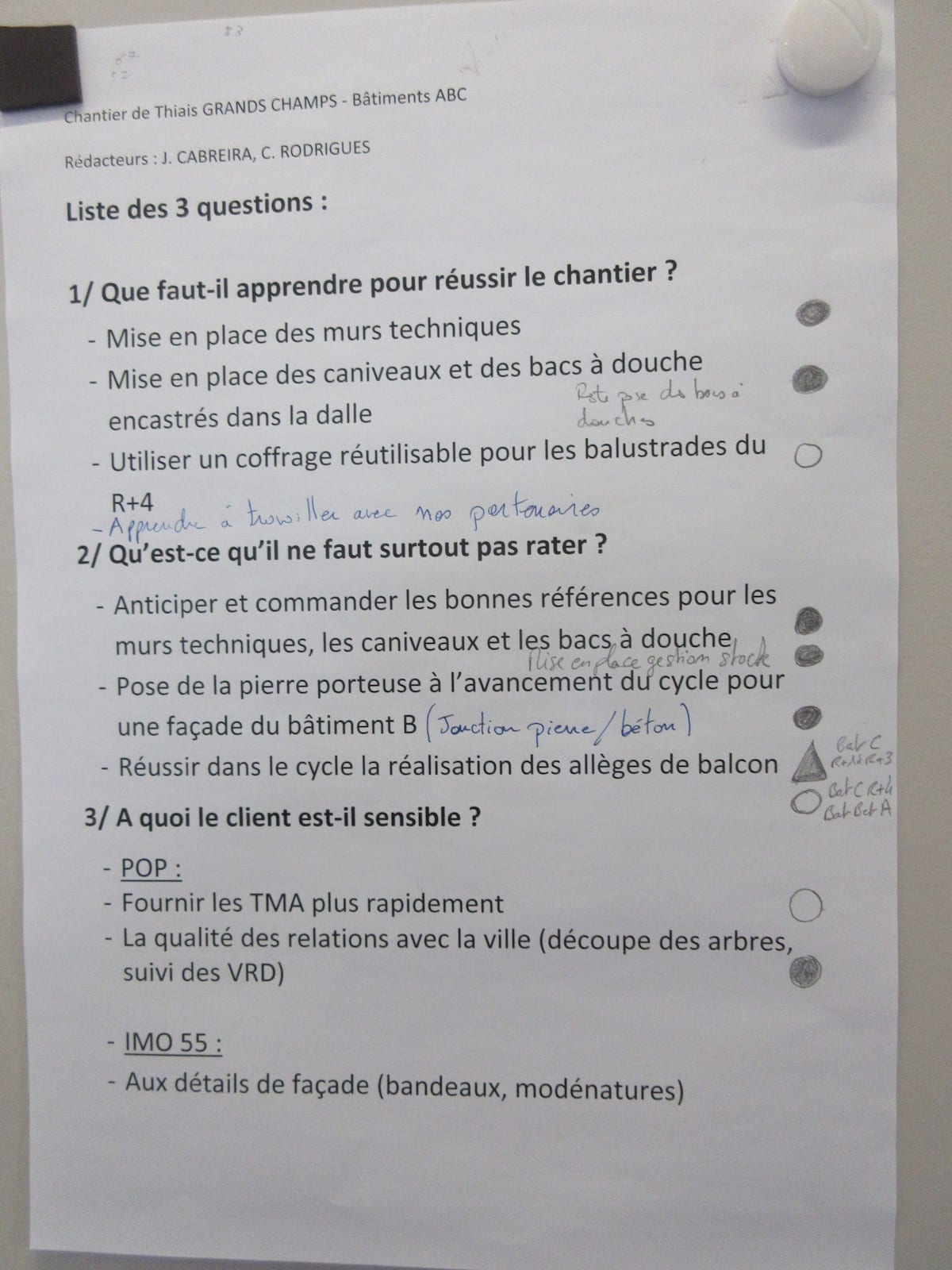

I had immediate proof that this is indeed a question on people’s minds at Paris Ouest Construction upon entering the first construction site and meeting the local site managers. There were three open points of discussion posted on the wall in the builders’ office:

- What new challenge do we need to learn about and tackle in this building? The answer turned out to be pre-fabricated bathrooms.

- What are the customer's specific expectations for this building? Avoiding water over-consumption (this building will be a residence for low-income people and water will not be charged to each individual renter).

- What can't we afford to miss on this building? Controlling the different cycle times for the new parts of the building and the parts we are simply renovating: the different work contents between new construction and renovation could alter the sequence of trades coming in one after the other in each of the apartments (drywall workers, plumbers, electricians, painters, and so on).

Focus is important, and Jean Baptiste has made it a routine to have all his gemba walks start with these points in mind (it is so easy to get side-tracked by the many process and contracting issues that normally occur on a building site). Indeed, on the second site we visited, asking those same three questions was again the starting point of our walk.

In the first site, we quickly turned to the problems listed on the office wall: an interesting discussion began on a rework related to the pre-fabricated bathrooms. They all came in a batch, right before the summer break, and were quickly placed in each of the future flats. When the building works started again in September, partitions were erected and the plumbing teams stepped in, only to discover that two bathrooms had been placed in the wrong flats. Partitions had to be taken down and the two bathrooms switched around.

Importantly, the discussion was not on the rework itself, but on how the company could avoid this type of mistake in the future. Jean Baptiste went even further in the second site we visited, challenging the team to think deeper about the idea of standards and a worker’s ability to check his own work for any anomalies. The ability to clearly define OK work and non-OK work is one of the most fundamental skills we can develop in people.

Jean Baptiste has a clear idea of what he wants. "I ask them to list at least one problem a day and discuss how they can prevent it in the future," he told me. "No problem is too small. In fact, I find that the smaller the problems I see being discussed, the higher the quality will be in the end. What worries me is seeing no problems!"

The last phase of Jean Baptiste's gemba walks (before walking the building site) is a macro-schedule of the key dates in the process, as they were initially set up. These are closely tracked to try and "save" each of them and stick to the original schedule. In both sites, the objective here was not to check the ability of managers to produce a detailed Gantt chart, but to keep them focused on major milestones. This systematic "save the milestone" approach, together with the small-batch attitude I will discuss in a second, helps Paris Ouest Construction to complete projects in 13 to 14 months, when it normally takes their competitors 18.

LEARNING TRADES

In the second site we visited, I also saw different experiments encouraging on-the-job learning.

Stock replenishment by pulled flow, for example, is being tested on technical wall parts (technical walls are erected with all the piping and wiring inside, which saves up to 0.5 square meters of space in the flat). Paris Ouest doesn’t directly work on the pipes and valves (the work of trades is outsourced), which normally come at a later stage, but the technical walls need to be taken care of: the company is taking advantage of this new flow of supplies to learn pulled flow.

We also saw a kaizen board that reflected on a new technique to produce concrete balconies (we looked at the experimentation plan and then went to see the result of the test out on the site, a rare opportunity to see a learning process live).

Most of us have seen a building site at least once. All kinds of trades work on it at any given time, but the most important thing to manage their work is the sequence, as partitions need to be erected before a plumber can connect pipes, an electrician the wiring, etc. And all this has to happen before a painter can paint. In a large building, many sub-contractors work at the same time, under an approximate takt-time of one flat per day, but what really struck me as we walked from one flat to the next was the cleanliness of some of the to-be apartments in which a trade had just finished working.

I was expecting to see tools, rubble, people, scaffoldings and ladders everywhere. So I asked Jean Baptiste how they manage that and he told me the two rules he and his team have set for the sub-contractors, to limit rework and idle time:

- Cleaning the working space as soon as they have finished and before they move to the next flat (rubble taken down, tools taken away, etc). This is more than 5S or respect for the next worker: just like in industry, workers tend to batch activities, selecting a week’s worth of work and the corresponding area and “occupying” the entire space so that they can interrupt and pick up work when and how they want. Since the takt-time is one flat per day, they tend to occupy an area of five flats each week. By doing so, however, they prevent other trades from moving in (even though they spend no more than 8 hours in each of the flats over the course of a week). The “Finished and Gone” approach of Paris Ouest Construction forces workers to break the week into smaller one-day batches: they now finish one flat each day and immediately clear out the flat. This approach allows for simultaneous work on different flats, reducing the overall lead-time.

- Auto-control by each worker, which means the expectations of the trade that will step in next are well understood. To that effect, Paris Ouest Construction has designed a one-page document, a sort of “OK first step” template, in which working conditions are set, as well as the quality requirements. The document is discussed with the worker ahead of the job, and an action plan is defined if necessary. This was a major departure from the traditional checklist audit carried out after the job is done.

As we came back down from the flats, Jean Baptiste started the debriefing of the gemba walk talking about the safety issues he had spotted. “Protecting the worker is the first step of quality management and the basis of respect,” he told me.

BUILDING QUALITY

Jean Baptiste’s approach to quality management has nothing to do with ISO (which more often than not is nothing more than window-dressing). It is people-centric, and based on two fundamental ideas:

- Understanding customer expectations, and if these cannot be easily understood, trying to see the building with the customer’s eyes at all times – because waiting for feedback on the show flat or just before the final handover is too late. Additionally, the “Finished and Gone” approach encourages trades to see their fellow trades as customers.

- Once the external shell is built, construction work is all about following the right sequence of trades on a site (all belonging to external tier-1 sub-contractors, which sometimes hire tier-2 workers). Building trust is therefore key, because it brings transparency and open discussions on problems. That’s why Paris Ouest Construction has tried to create a safe working environment where people can highlight problems and easily fix it or escalate it (if they need help).

The company’s approach to quality management is lean thinking at its best – regular gemba walks, real customer focus, consistent monitoring of what must be achieved or improved, openness to learning from problems, presence of top management on site, and attention to safety, delivery and quality.

While not easy, paying attention to details eventually pays off for Paris Ouest Construction, leading to a number of innovations: for instance, their in-house solution to thermal bridges (one of the main sources of energy waste in a building), which is a best-seller and outperforms off-the-shelf solutions in terms of aesthetics, effectiveness, and ease of installation. The development of the solution resulted from the observation carried out on building sites (teams were unhappy with previous solutions) and from the collaboration of several departments.

If you are still not convinced this approach works, here’s a few figures: the lead-time for the upstream structural work (entirely and directly managed by Paris Ouest) has improved greatly, with an increase from 40 to 80% of the jobs completed in full and on time. Progress is being made with the work of trades as well, even though this is of course more difficult to map and measure.

There is more. The number and seriousness of accidents have been decreasing consistently over the years, thanks to the continuous focus on safety.

Finally, innovation and kaizen have contributed to the 47% reduction in carbon emissions by Paris Ouest Construction in the four years between 2010 and 2014.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – With more and more organizations in the service sector adopting lean thinking to turn around their modus operandi, it only makes sense to highlight the struggles and misconceptions they still encounter.

INTERVIEW – We have come to dread having to interact with customer support representatives, and quite rightly so. Basecamp has made it a mission to bring humanity back to this interaction.

FEATURE – ME Elecmetal in Chile applied Lean Product and Process Development to cut lead-times, boost collaboration, and build a sustainable system for innovation.

COLUMN - For those working in the I.T. world, identifying waste can be tricky. However, starting by tackling over-production will help you to eliminate every other form of waste.