Is our response to Covid-19 fundamentally flawed?

OPINION – Discussing the lack of structured problem solving in the fight against the pandemic in Italy, the author makes the case for blanket-testing as a possible way to understand the current state.

Words: Matteo Consagra, Lean coach, Istituto Lean Management – Milan, Italy

Over the past couple of months, our countries have had to make unprecedented decisions and adopt measures that, until a few weeks ago, would have been considered unthinkable. Understandably, the debate on how to react to the Covid-19 emergency has been raging for weeks, monopolizing our attention and our daily conversations. Like many of you, I have been thinking a lot about this myself, ever since – back in February – we in Italy realized the pandemic was going to hit us with full force. I had been reading with interest (and apprehension) about the response to the onslaught of infections in countries like China and Korea and, as the virus continued to spread around the world, I began to ask myself questions about the different approaches that the different governments were implementing.

With Covid-19 securing its grip on our lives for the foreseeable future, it’s clear that more difficult decisions will have to be made. That’s why I believe it’s important to scrutinize our response until now, understand what we have gotten wrong and rectify it, so that we can find a way out of this mess and develop the right mindset to start thinking about the aftermath.

As a lean thinker, my instinct is to approach the analysis of our predicament like I would any gap between actual results and expectations: using the scientific method. Relying on PDCA is the only way we can ensure our decisions are based on data – not conjecture – that we can use to grasp the root cause of our problem and eventually solve it. Because the problem at hand is the health and wellbeing of the world population, I think that facing it in a structured manner is more important than ever.

Every time I read about the measures that are being adopted across the world to fight Covid-19, my thinking process gets stuck almost immediately at the definition of current state. The noise around the pandemic is simply deafening: virologists, reporters, politicians, workers’ associations, economists… everyone seems to have an opinion on what to do to contain, delay or stop the spread of the virus. As I see it, the only real corrective action is to develop a vaccine and make it available to everyone; anything else can only buy us time and ease the pressure our healthcare systems are under. There are tons of data out there, and it gets constantly updated. But that alone doesn’t seem to be enough to help me understand and define the current state (in fact, it’s adding to the confusion). So, I wonder: what is it that I don’t know? Is this the right information we need right now to face this problem?

Let’s look at this more in detail. What I see is either lagging data (that is, a posteriori, like the number of people in the ICU or the number of deaths) or incomplete data that refers to a very small sample of the population and is therefore not a reflection of the real situation (if it were, Italy would be seeing a mortality rate of 17%). There are very few leading indicators being currently used that can effectively inform our decisions on the best way forward. For example, we talk about social distancing (without a doubt, an important measure), but what about the viral load of an infected person?

WHERE IS THE ALIGNMENT WE NEED?

The Coronavirus is, not surprisingly, the most common subject in my conversations with friends, relatives and colleagues – in particular, we are all interested in understanding when we might go back to something that at least resembles normality. There are three main elements inspiring our points of view. Some are informed by economic considerations on the effects of the lockdown on the business world (countries enforcing the lockdown vs those that don’t). Others stem from the political considerations on the motives leading politicians to make, or not make, important decisions for fear of losing votes or damaging their image (I am thinking of the constant bickering between the central and regional governments in Italy, but also the open disagreements we have seen time and time again between Donald Trump and the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dr Fauci). Others still are shaped by social considerations (from the chilling idea of herd immunity, initially put forth by the UK government and somewhat carried out by Sweden, to what some have defined as “Italy’s gerontocratic policies”). I have noticed how people tend to lean toward one of these three aspects and sacrifice the other two. For the most part, the arguments presented are sound and certainly based on the information that is currently available. So, again, what are we missing? Is the data we are looking at sufficient to make decisions on what to do next in a scientific way? No, it is not.

The main problem I see – aside from the tragic lack of a coordinated global response – is the fact that, in my opinion, any choice we make is nothing more than a gamble until we effectively map all the infected, both people who present symptoms and those who don’t. (By the way, the cost of losing this bet is more human lives now and more economic damage in the short to medium term). This entails “blanket-testing” to identify people who might be carrying the virus without showing any symptoms as well as those who have already contracted it and might now be immune. In the small town of Vo’ Euganeo, one of the early hotbeds of the epidemic in Italy, all 3,000 inhabitants were tested, identifying a number of positive cases that until then hadn’t made it into the statistic. This example tells us there is clearly value in this approach. Yet, whenever I make the case for more testing, point out how very little of it has been done in Italy to date (often limited to a specific category in the population) or criticize the lack of public or private initiatives aiming to correct this gap, I am told that there is not enough capacity in the system to perform all the tests that we need to run.

One more time, I am reminded of all those times during my coaching sessions when, faced with a problem, my coaches have described the countermeasures that can be implemented, rather than those that should be implemented (perhaps at the cost of changing something in the structure and processes of the organization). As a lean problem solver, I simply cannot accept that weeks after the onset of the pandemic we are still unable to follow the South Korean or Singaporean model and blanket-test the population of our countries. I cannot accept that those in power are unable to make decisions based on a structured problem-solving approach. Here in Lombardy, the region most heavily affected by Covid-19 in Italy, we have just seen yet another example of this lacking approach, with the launch of an App that allows citizens to anonymously share information on their health status: while this is undoubtedly useful from a statistical standpoint, it will not be enough for us to resume our lives and restart our economy.

A possible solution is right in front of our eyes: several companies in the private sector have already confirmed their availability (indeed, their interest) to support the collective fight against Covid-19. At least two of the organizations I am supporting are already doing it, or trying to: FPZ Spa, which was recently featured here on Planet Lean, is using its 3D printers to produce connectors for scuba masks transformed into supports for ventilators, whereas IGB srl has been waiting for days for the authorization to produce over 50,000 masks per hour. We can easily imagine the same dynamic applying to the production of testing kits, which we could inject into the system by the thousands within days. The products are out there, like a point-of-care testing kit developed by Abbott that can be used by any physician and provides a result in just five minutes. So why can’t we use them more extensively?

For any of this to happen, we need our governments – at different levels and across the globe – to look at the data and give the idea of blanket-testing more consideration: it might represent a way out of this tragic situation. I am not claiming this is the only element that’s missing to clearly define the current state (indeed, blanket-testing is one of the possible solutions to our problem), but there is no doubt it would shed a much-needed light on the problem at hand. Dividing the population into different categories based on the test results, age group, previous health conditions, geographical area and profession would allow us to create protocols that minimize risk and flag up the “exceptions” telling us where we need to act. This way, we could stop the all-too-common profiteering around PPE and hand sanitizer and restart industry and trade while minimizing the risk of a second wave. Upon recording the presence of the virus, we could act swiftly to isolate people who need isolating, thus avoiding situations in which we are looking with suspicion at everyone else – from our neighbors or at fellow shoppers in line at the supermarket.

While achieving a complete and precise mapping of the population is unrealistic (if anything, for the time it would take), exponentially increasing the number of tests performed would allow us to base our decision-making on solid data, rather than assumptions – like lean and PDCA teach us. As Peter Drucker said, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

This article is also available in Italian.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – Through this intimate anecdote from her days at Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky, the author tells us of her experience with standardization… and of the deep leadership lessons hiding behind it.

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - Given the name of this column, it only makes sense to analyze the word yokoten. So, how can we effectively help others to apply what we learn at the gemba? What makes yokoten successful?

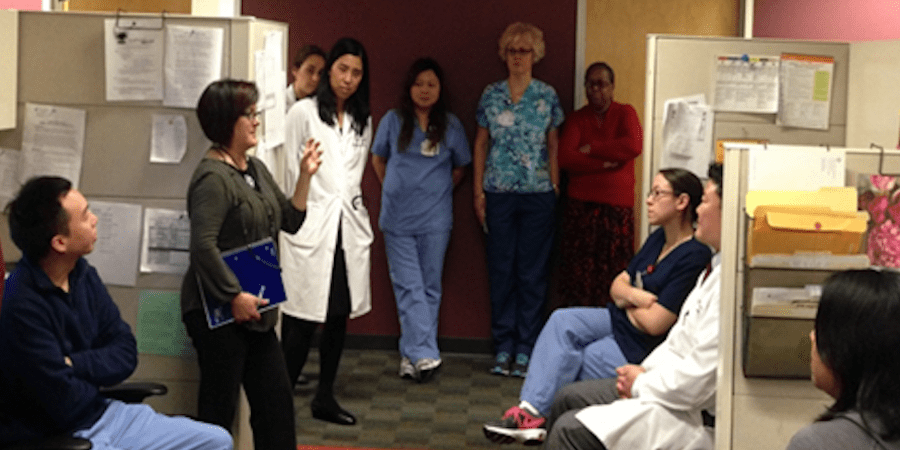

FEATURE – The Palo Alto Medical Foundation has used lean to redesign workflows in its primary care clinics since late 2011. With changes now spread to a total of 17 facilities, the team started to analyze what it took to sustain the results achieved.

CASE STUDY - An approach based on Lean Daily Management System and experiments in a model area led an Italian manufacturer of combine-harvesters to become one of the leanest organizations in the Veneto region.