Practice makes perfect

FEATURE – Much like lean management, attaining perfection in music requires constant practice. The author looks back at his musical past and at a recent Lean Global Network samba gig.

Words: Dave Brunt, CEO, Lean Enterprise Academy – United Kingdom

Quietly, we made our way into the main hall of Salgueiro, one of Rio de Janeiro’s most famous samba schools. Our silent march, together with the expressions on our faces as we looked around the large, empty space, betrayed a mix of curiosity and wariness – the two most common emotions accompanying any new experience.

Sporting purpose-made red vests with the signature logo of the Lean Leaper, our team of around 45 from the Lean Global Network formed a semi-circle around the main stage. Within minutes, a team of coaches from the school appeared to take us through the fundamentals of samba and demonstrate how to play the different instruments used in this captivating African-Brazilian music genre.

I can’t say I have any experience with the samba, but I have played the cornet and trumpet. I started when I was 6 and played in bands and orchestras until I was 22. Work then got in the way, but I still play carols every Christmas. Regular practice made me fairly proficient. I achieved Grade 8 (the last of the formal music exams) on the cornet by the age of 16. I played in both my local Brass Band and the County Youth Brass Band touring Denmark, Portugal and Germany. We also played at The Royal Albert Hall, which was a fantastic experience. I really enjoyed playing, and music is still something I am passionate about. So, you can imagine how big of a treat the experience in Rio was for me.

After receiving our samba crash course, we were divided into groups – one for each instrument. A bateria – the drum orchestra playing the samba – features several instruments, from the big surdo drum to the chocalho jingle stick. Amazingly, this orchestras can have more than 300 percussionists!

To allow each LGN team to familiarize themselves with their instruments, routines were explained to us slowly and many times. For example, for instruments like the chocalho, which produces different sounds depending on how you move it, each routine was broken down into steps to make it easier to learn. Some of the LGNers were all too keen to start, as proved by increasingly persistent ta-ka-ta-ka-ta-ka’s and bum-bum-bum’s echoing through the hall.

It was finally time to rehearse. As expected, our first experiment resulted in, well… a lot of noise (when the only instruments around are drums, the line between noise and music is a fine one). Everyone gave their own interpretation of how the instruments should be played, the spectrum of skills ranging from the promising to the tone-deaf, from those diligently following the coach’s instructions to those randomly hitting the drums.

The event – which was organized by Lean Institute Brasil as part of our annual Board Meeting – aimed to teach us about Brazilian culture, but it was also a team-building exercise. Indeed, as the evening went on, the worried expressions people had entered Salguiero with gave way to fun and relax, as the group of lean thinkers started to come together and go with the flow (pun intended).

LEAN AND MUSIC

Following rehearsals – during which we practiced as individual subsets of the bateria as well as a united orchestra – it was time to let the professionals take over. (I could see the relief in the eyes of the conductor.) The community was about to come together for their own rehearsals (schools participate in the world-famous Rio Carnival every year), which gave us lean thinkers a chance to observe from the sidelines.

Within minutes, the near-empty school filled up with hundreds of people from the neighborhood forming a gigantic square-compound (quadra de samba). As I watched them begin their practice, I was in complete awe. I had never seen anything like it: people from all walks of life, a lot of them, coming together with the sole purpose of creating music. The only thing distinguishing them was the instrument they were playing, which determined where in the group they were going to stand.

Overall, there was little interaction between people, as everybody seemed to concentrate on the music. (The noise produced by a couple hundred people playing the drums makes conversation rather challenging anyway.) I quickly noticed how people kept coming in, seamlessly joining in with the bateria minutes after they had begun playing. This caught my attention and had me reflect on how well they must have known the technique (or the standard beat, if you will) to be able to do that. So well had it been explained that a simple signal of the conductor was enough for people to know what to do.

Over the course of the following hour, during which the music hardly ever stopped, I reflected on the many similarities between the samba-playing group, lean thinking and my own musical experiences. Much like in an orchestra, the conductor was setting the beat – or takt time, as we lean thinkers would call it. He would make a signal with his hands, and the beat would change. This group was large, so in the sea of percussionists, a few individuals were tasked with relaying the instructions the conductor was giving. It was fascinating to see how the work of about 200 people was being coordinated. Having these key people reproduce the messages of the conductor is a clever way to ensure everybody sticks to the beat and that no information is lost – much like a group leader (line manager) would interact with team leaders in a production plant. Come to think of it, the role of a manager is very much akin to that of a conductor!

It was also interesting to observe how the conductor reacted when one of the sub-groups made a mistake. No blame, just focus on process (the work to be done). He had everyone else stop playing and focused on the group that needed more practice. The technique was remarkably similar to that used by my cornet teacher, Derrick Margerson. He taught me from age 11. He never once raised his voice, was always calm and made every lesson fun. When you couldn’t play something, he’d have you break the music down. Initially, it might be as little as two notes, then a bar (a bar might be 4 to 8 notes) before working either side of the bar. Finally, you would play “the phrase” – from when, as a player, you had taken a breath up to when you needed to take the next breath. Mr Margerson didn’t waste time practicing the things you could do, he focused on what you couldn’t do, before pulling the total piece of music together. It was amazingly effective. In Brazil a similar routine was followed. The sub-group that was struggling played four bars for around 20 seconds, time and time again, until they got it right. Only then did the rest of the bateria resume playing. This micro-rehearsal was a very effective way of isolating the problem (it’s easy to see if something is wrong because the work is standardized), and yet another reminder of how important mastering the work is.

This reminded me of the work we have done in the workshop at Halfway Ottery in Cape Town. When vehicles come in for servicing and repairs, if the reception doesn’t happen seamlessly, it is all too easy for a bottleneck to form. What we did there was coming up with a solid process (we created the music, if you will) and then breaking it down to have people practice it over and over again. Once we did that, we were able to identify those traits making one a great receptionist, like the ability to lead the conversation with the client in a very natural way. Breaking down the work in different steps was also how we turned around the Sales Department, whose success can be attributed to two factors: a good conductor, Sales Manager Calvin Govender, and constant practice, using job instructions to improve the work.

As the bateria in Salgueiro kept rehearsing – by this point, the rhythm had most of us move and sway and tap our hands on the railings – it occurred to me that we were witnessing a community-building exercise. Not everybody who was at the samba school that night was a professional drummer. In front of us was a community coming together, not an orchestra.

And yet, through practice, a mistake-proof system of breaking up the work (in this case, the rhythm), teamwork, a few visual cues and a good conductor, the bateria was able to create purpose out of chaos.

The biggest lean lesson of the night for me was that there is no limit to what people can achieve, so long as they are given the tools and the opportunity to hone their skills through practice around a common purpose. This is how a diverse group of people can come together and create an exhilarating musical experience that has all of Rio de Janeiro dance every February.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

PROFILE – What does one learn from working for Toyota over 40 years? This Australian leader has developed a unique holistic view, and a strong set of technical and social skills.

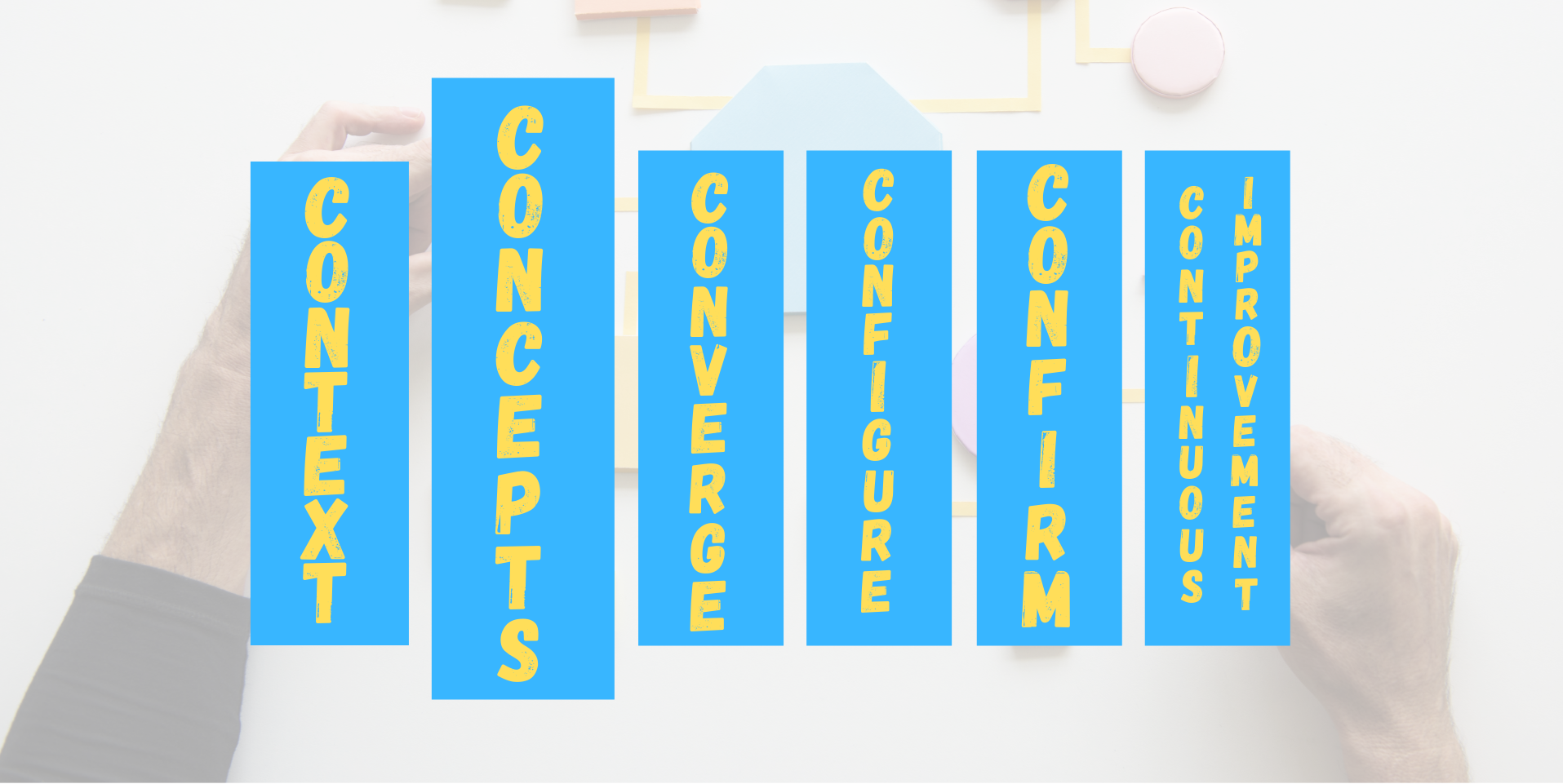

SERIES—The authors discuss Concepts, the second of six elements in their process development model, discovering the key knowledge gaps and exploring multiple process design options to facilitate learning.

FEATURE – The pandemic has brought back into the spotlight the common misconception that Just-in-Time causes disruption when spikes in demand occur. Torbjørn Netland debunks the myth.

INTERVIEW – We chat with the CEO of a construction company in Dubai to learn about the competitive advantage that lean thinking is providing them.