Learning to be lean chameleons

FEATURE – In this candid, personal account, the author shares her experience as a lean coach, her challenges and success, and how she adapts to different situations.

Words: Teri Laeder, Process Engineer, Zingerman’s Delicatessen Inc.

I was brought on as an apprentice at Zingerman’s five years ago. Tom Root – a Managing Partner at Zingerman’s Mail Order – needed help with all the different projects he was working on across the community of businesses and saw the value of having someone shadow him as he went out and tried to spread lean throughout the organization.

I didn't know anything about Lean Thinking back then. Because of my engineering background, I had heard about Six Sigma and the idea of improvement and experimentation. None of that was new to me, but the actual application of those ideas and techniques in the real world was a different matter.

At first, our approach was very much “push”: directed by our management team, we went to businesses with potential to introduce them to the tools and knowledge that Tom had acquired through his experience with lean at Mail Order. During my first year of apprenticeship, we welcomed a group of students of Dr Liker’s (I myself attended his class on Kata) to Mail Order. We divided them into teams and took one of them to our delicatessen. This opportunity was really our foot in the door to start spreading lean across the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses.

After talking to manager Laura Wonch, we had the opportunity to work on the sandwich line – specifically on corned beef waste. We introduced the idea of the eight wastes (most people recognize seven, but to us untapped intelligence is a huge form of waste) and started to see what we could do to improve the situation. We actually didn't have much visibility of the current state, but we decided to focus on corned beef because it was a “high mover” – the Reuben is a staple sandwich moving through the deli. We knew that a little incremental improvement would make a huge difference overall and figured it would be a quick, easy way of applying foundational lean principles and getting some quick wins.

It was one of the first lean projects I participated in, and I learned so much from it. To begin with, I had no idea it would take so long just to get a clear understanding of the current state. The lesson here was that it is very difficult to measure an unstable process: we had to bring some standardization to the deli sandwich line just to be able to collect data and map the current state of how much corned beef we were wasting. It was also the first time I experienced the infamous “resistance to lean” so many of us have to deal with in our transformations. Staff in the deli felt that collecting the data we needed meant extra work for them and struggled to see value in it. We spent a lot of time with them, sharing our every learning and helping them to see that their job is more than being just a pair of hands on the line. We needed their intelligence and experience, too, to drive the business forward.

As a lean coach, you need to remember that not everybody comes to work every morning wanting to do continuous improvement and accept that not everybody will be excited to see you. What we were asking of people was to embrace a new way of thinking about the work and, to get there, the line manager’s support and buy-in was critical. Laura is a great manager, who was able to create an expectation that people’s work is no longer just to prepare sandwiches, but also to measure waste and help to improve the process. Even though pockets of resistance remained, this helped immensely.

LEARNING TO ADAPT

When I started, I was really forceful and that didn’t work too well. Lean Thinking is not something that can be imposed. People will take the information when it feels right for them, when they hear something that clicks. For me, it is really important to allow them to go down that path at their own pace.

I've learned it's beneficial to work hand in hand with people, get on the same page as them and show humility. I don’t want them to see me as the “expert” claiming to know how they should do their job. I just happen to have a set of tools and principles that, combined with their experience and understanding of the work, can help us transform the business together. Practically, this means you can often see me on the line slicing corned beef and reading SOPs.

It's important to get everyone on the same page, because what is crystal clear to us as lean coaches might be harder to see for people at the front line. That’s why in the Zingerman’s Community of Businesses we like to base our every activity on a well-defined vision – in our case, one that aligns with our three bottom lines (Great Food, Great Service, Great Finance).

And still, as a lean coach I need to be able to translate that vision – or the latest the improvement initiative we embark upon – into something that different people will be able to understand. I am a data-driven person, but not everybody is. Many people hate numbers. Some are really competitive, and respond well to games and contests. Others like to follow standards. Others are very visual. Different people are compelled by different approaches.

It all starts with who the learner is. In our lean project at Cornman Farms, the improvement team dealt directly with the managing partners of the business, for example. That provided a different type of challenge: with the business owners so enthusiastically engaged, the risk is that the implementation will be very top down. To avoid this, I made sure I spent time at the gemba, doing the work and proving to people that I care about it. About them! I always do this, even when we have buy-in from management from the very beginning. It’s a matter of showing people I am not there to judge them, but to help them improve the work.

In many ways, a lean coach needs to be a chameleon to adapt to the million different situations she will be facing. It’s about really finding what matters to people. At Zingerman’s, is it the quality of the food that they really care about? Is it that they really care about the people they are setting up a wedding for? It’s all situational.

Of the many different situations that I have found myself having to adapt to, the most challenging was by far the project in our candy company. The business had recently gotten a loan to move to a brand-new facility and buy some equipment. They were confident they would be able to comfortably pay it back. However, the business quickly found itself struggling. I was sent there to help and, at the same time, the manager was pulled away for personal reasons and I had to step in for him. That’s when I became the production manager. I had spent time learning about the business enough that slotting me in there wasn't really a big deal. The difficulty, however, was the previous manager had been driving the whole business on his own and all the information I needed had left together with him. It was a tense situation, made worse by the fact that I had never worked as a production manager and that we were approaching the holiday season – our busiest time of the year. That season did not go well, but it taught us so much that we were slowly able to make a move towards a leaner system. We implemented visual management and standards for the preparation of candy (we made recipes very visual, which made it easy to onboard temporary workers), and created a marketplace of finished good replenished using a Kanban system. The biggest challenge in that environment was that people were used to constantly going to their manager to validate the decisions they were making, whereas I wanted them to become more autonomous in their work and problem-solving capabilities. We worked hard to empower the front line and get them to understand they are the experts, not us. It eventually worked and today the business is doing great under their new manager. So, the most challenging situation was the most rewarding, too, eventually.

Over the past five years, I have had to change my stance many times, just to do my job as a lean coach. I have had to be assertive, I have had to be supportive, I have had to be a data person, I have had to be a psychologist, I have had to be a production manager, and so on. This job certainly requires wearing different masks. Don’t get me wrong: I am the same person everywhere, but I pull out different attributes depending on where I go.

WORKING TOWARDS YOUR OWN OBSOLESCENCE

When Tom Root hired me, he told me that the role of the “lean team” was to pass on its knowledge and then not be necessary anymore. To me, this makes perfect sense because, if done well, continuous improvement ends up being staff-led – with people starting to share ideas about how the work can be improved. To get there, I find what speaks to the learner I am working with, hand over the tools and encourage them to learn as much as they can from their process by experiencing change first hand. Eventually, the manager becomes the coach and can start training staff and empower them to speak up when something isn’t right.

One day, my job as a lean coach will no longer be needed. Until then, I will share the lean knowledge we are acquiring from our experience with as many people across the organization as I can, to facilitate their transformations. I myself have greatly evolved over the past five years, having learned so much from all the experiments we have been running. More importantly, I have a much deeper appreciation for the different types of people that are in our business. It is such a gift to get to know them better and figure out what really drives them to come to work every day.

Starting next month, Planet Lean will be publishing case studies on some of the Zingerman’s businesses undergoing lean transformations. Stay tuned!

THE AUTHOR

Read more

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - If you are going to succeed at one of your resolutions for 2016, let it be that of always starting off a lean transformation with a deep analysis of the work at a single point in your organization, and then escalating your efforts to reach all the factors influencing the work.

FEATURE - Planet Lean launched exactly one year ago. Editor Roberto Priolo offers some reflections and a round-up of the most popular articles we have published to date.

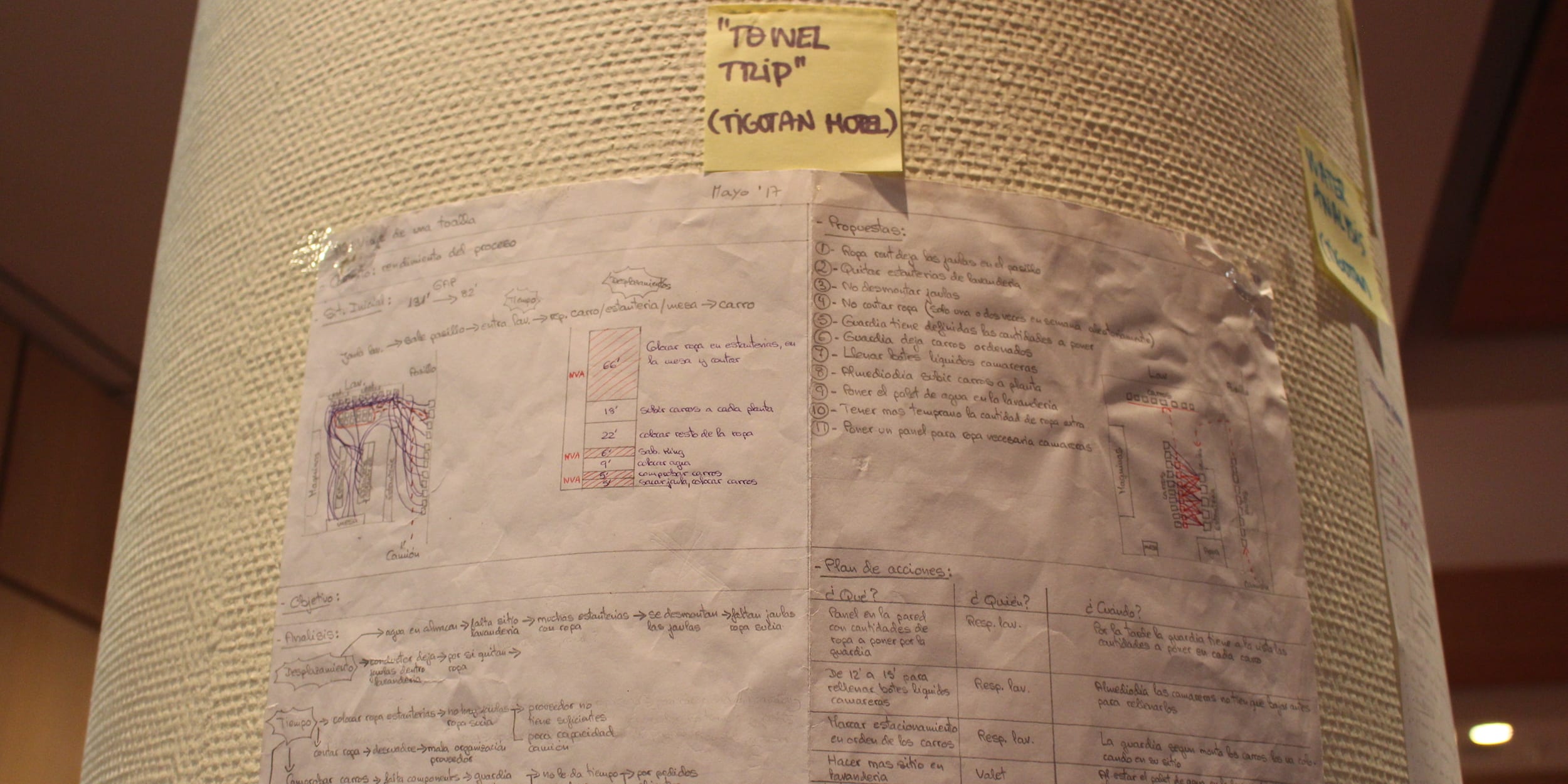

VIDEO – The director of a hotel in Tenerife explains the first steps the team is taking to develop a lean daily management system, and how this connects to the organization's hoshin.

PROFILE – It isn’t every day that you come across a hospital CEO coaching people on A3s and following his own standard work. So when you do, it’s important to share their story. This month we profile the CEO of a Brazilian cancer treatment center.