Jim Womack shares his lean take on Tesla

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – In his first column of 2018, the author looks at one of the most talked about companies in the world, Tesla, from a lean point of view.

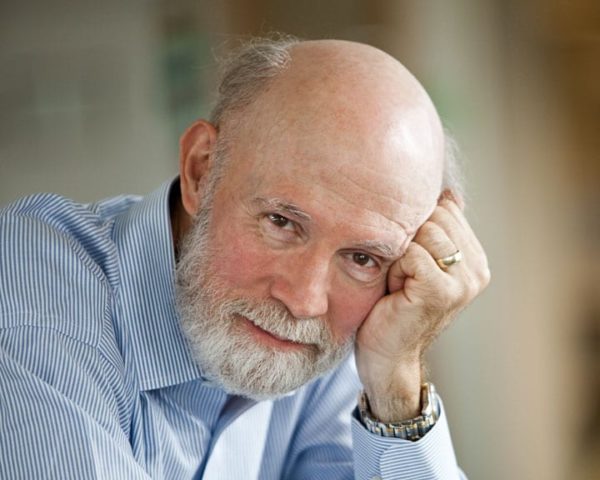

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

Tesla is a start-up company as well as a business phenomenon that’s important for the Lean Community to understand. With its direct sales model and planned lights-out factory, it purports to be the next new thing in industrial thinking after Ford (mass production with modern management) and Toyota (lean production with lean management.) In addition, it claims to be a harbinger of the next “industrial/business revolution”. (Are we up to number three now, or is it number four?) This will combine an industrial company with a green, internet, AI company to offer not just a physical product but low-carbon, autonomous, hyper-connected, shared mobility for the greater benefit of humankind. Plus – and what revolution does this fit in? – founder Elon Musk will use the profits to finance a personal trip to Mars!

The vastness of the Tesla promise and the hyperkinetic nature of its founder have in recent years sucked all the air out of the room for old-fashioned car companies in general, and perhaps Toyota in particular. So let’s take a look at Tesla through a lean lens, asking what’s really new and better here and what it means.

Tesla’s start in 2004 was consistent with thinking in the lean start-up community about new product development. Its founding team knew little about automotive design and production, so they decided to keep things simple by developing a prototype that tested only what they did not know: The reaction of consumers to a pricey, fast (0-60 in 3.9 seconds), long-range (244 miles) battery electric vehicle (BEV). Instead of designing a vehicle from the wheels up – as other BEV initiatives did, from General Motors with the EV-1 to a multitude of start-up companies – they decided to retrofit their power management system, motor, and battery to a Lotus Elise, already in production for many years. To make it appear new they covered the Elise space frame with a new plastic skin at low cost.

This minimum viable prototype (MVP) worked brilliantly to quickly confirm strong demand for, and positive user experience with, a type of vehicle never before available, with only a modest investment to put 2,450 vehicles in the hands of paying customers. (One of these is slated to go into orbit around Mars on the first launch of Musk’s SpaceX Falcon Heavy lifter in February, a feat that will, if successful, boost Elon Musk into a promotional orbit of his very own far above P.T. Barnum and dear, departed Steve Jobs.)

Tesla’s approach to the customer was also broadly consistent with lean thinking. By selling vehicles directly to customers and keeping in continuous touch with every customer through the internet, Tesla proposed to create more value with less resources, the essence of lean. An additional breakthrough was to continuously update each vehicle’s software to allow new features and to correct problems reported by vehicles in use.

(The latter concept is now being copied by all auto companies but I do worry a bit about the potential to widely and instantly install bugs – including those from hackers. Apple just crashed my iPhone by installing an updated iOS during the night. What if it had been my Tesla that crashed instead? Note to readers: I don’t have a Tesla so it can’t crash. But I do enjoy driving friends’ Teslas, which put a smile on my face every time, and I certainly don’t want them to crash.)

These early innovations seemed to head Tesla in the direction of a lean enterprise. But when Musk moved to the next step of creating a volume car company, once the BEV concept was proved for the Roadster, things begin to diverge from the way most in the Lean Community would proceed.

Tesla commenced a practice, repeated for the S, X and 3 models, of setting extremely ambitious launch dates and then steadily slipping them as problems were encountered with the beta versions of the vehicles and beta versions of the production system being used to build them. In the end, the actual time to market seems to be no shorter than the best of the traditional car companies.

Elon Musk is by universal agreement a brilliant visionary, so why do product launches always take twice as long as promised? Because, as Musk told Ashlee Vance in an interview for his very informative book, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, he sets launch dates that are half the time he thinks will actually be required. He then launches production with beta vehicles and a beta production process and suffers through “production hell” to get to full volume, an approach he believes will bring out the best in Tesla employees. And, who knows, they might even finish early!

But there is probably a more important reason for crazy launch timetables: Starting a car company of whatever description takes vast amounts of money and time, and new-entrant Tesla needs to keep hope alive for investors as it periodically goes out for more funding. (Musk also always underestimates the funding required.) Two years and X billion dollars for a new vehicle just sounds like a lot more bearable burden for investors than four years and 2X billion. And, once the funds are raised, most new investors tend to lock in – even if the share price starts to slump – until the product is fully launched and business results can be assessed.

So launch mis-estimation may mostly be a fund-raising tactic. But it is absolutely not lean: Enormous effort and cost are required for extended periods to produce and rework vehicles while completing the design and the production process. And this approach must work soon for the Model 3, now years behind Musk’s original promise, given its mission of proving that Tesla can be profitable with a mass market car. (Or will it prove to be an MUP, a maximum unviable prototype?)

Even if the Model 3 hits its volume/price targets, Tesla will need to find a better way going forward to design and produce vehicles, manage suppliers, and run its affairs. Otherwise at the price point and volume that any Tesla vehicle can command in the market I doubt that Tesla can reach the cost point needed to produce the margins that spell success. This better way of proceeding is called lean and it’s as old-fashioned and as effective as dear, old, currently-boring Toyota.

So my lean sum-up on Tesla reads as follows:

- Lean-worthy innovations in the initial prototype and the sales process.

- A product and process development system that violates all of the rules described by Jim Morgan and Jeff Liker in The Toyota Product Development System, delivering fully-launched vehicles no faster and with enormous amounts of cost and rework.

- A production system that promises a high cap-ex, lights-out, technology leap to eliminate practically all of the touch labor in assembly but which for the foreseeable future is simply a bad mass production system. (Toyota has been doing many experiments in recent years to get the right mix between robotics and humans and has concluded that for now robots are pretty good at helping humans but can’t yet replace them.)

- A supplier management system that routinely drives suppliers crazy. (I recently asked a supplier serving most of the world’s OEMs who their worst customer was and got the answer: “Tesla by a wide margin. How can you do a good job for someone who can’t tell you the final product specification and when to deliver?”) Going forward, why are suppliers going to give the highest efforts to Tesla?

- A general management system that favors heroic action by the senior leader (complete with a sleeping bag at the end of the assembly line to spur the lads on as they slog through production hell created by the senior leader’s crazy schedules) and that seems to deeply disrespect both managers and workers, who continually head for the exit or are pushed out.

But wait: Mightn’t there be better news to come? Tesla proposes to be the first car company to successfully switch the definition of value from the product to the mobility experience. Maybe green, autonomous vehicles that are shared will provide a path to the Tesla lean enterprise?

Who knows what may be possible and it is this part of the Tesla story that must justify the crazy market cap, with Tesla – currently producing slightly more than 100,000 vehicles per year – valued more highly than Ford producing 6.4 million. The problem is that every company in the automotive and IT and AI worlds is trying to do the same thing with the same technologies, most of them with more robust and lower-cost development and production systems than Tesla. They may all succeed (which could be a very good thing) or all fail (which would be a very bad thing), but it is unlikely that only Tesla will succeed or succeed far more than the others.

Herein lies the great threat to the Musk dream: Tesla winds up as a high cost, slow-to-launch, quality-through-rework manufacturing company that can’t be bailed out by a sustainable advantage in autonomy, asset sharing, and harvesting user data for re-sale. I’m sure a good dose of lean thinking on the vehicle side could minimize this risk, but I wonder if any of us in the Lean Community will ever be asked to provide it.

Looking at the bigger picture, an original Roadster (red) is about to go to Mars (“a red car for the red planet” in Musk’s recent tweet) and the traditional auto industry, including stodgy Toyota, has been forced by Musk to think creatively about the future even if Elon and his company never make it. This is surely a contribution to human life that many lean thinkers can admire, even if we would never have done it Elon’s way.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

CASE STUDY – This Polish debt collection company is refocusing its work around true customer needs and increasing problem visibility by implementing hoshin kanri.

INTERVIEW – In the face of rapid change, UniCredit Bulbank embedded Lean Thinking to simplify work and empower front-line innovation, proving leadership thrives on teamwork, continuous improvement, and adaptable processes.

FEATURE – Visuals are a natural way in which human beings learn and teach. The author discusses why visual thinking is part of our DNA and the implications this has on our lives at work.

FEATURE – We often think that making every product customers might want – no matter how little they sell or how much complexity they add to our schedule – is inherently lean. As Toyota understands quite well, however, it is quite the opposite.