Harada-san and the steps to better Jidoka

FEATURE – In the first piece of a series on Takehiko Harada’s contribution to TPS, the authors discuss the Nagara Switch and how it helps to achieve better Jidoka.

Words: Toshiko Narusawa, Joe Lee and John Shook.

“As a matter of fact, that was me,” Harada-san told me, when I asked him who had made the first Nagara Switch at Toyota. I had been trying to learn the roots of nagara for years. Harada continued, with a smile: “Why do you want to know such an old story? No one at Toyota cares who made it first. That was just one of thousands of small improvements we made in those days. If anyone had insisted on individual recognition of such a contribution, we would have been laughed out of the room.”

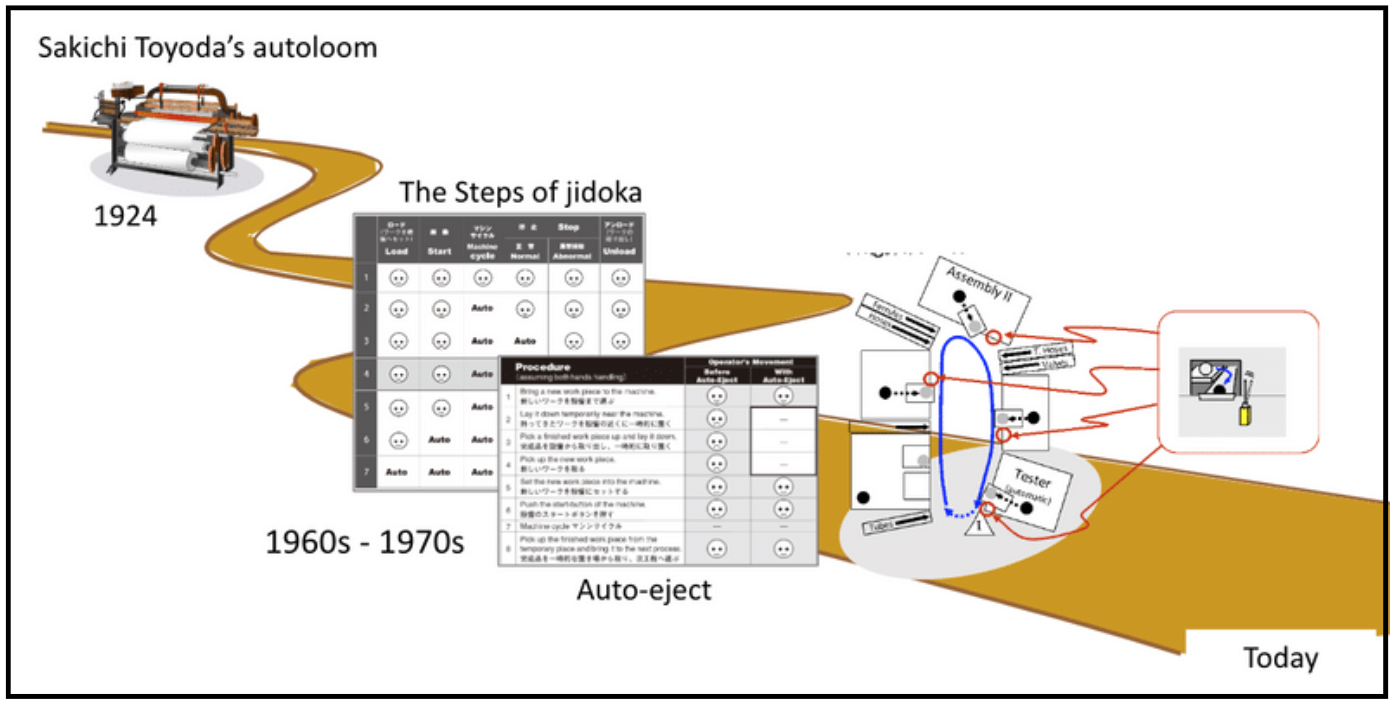

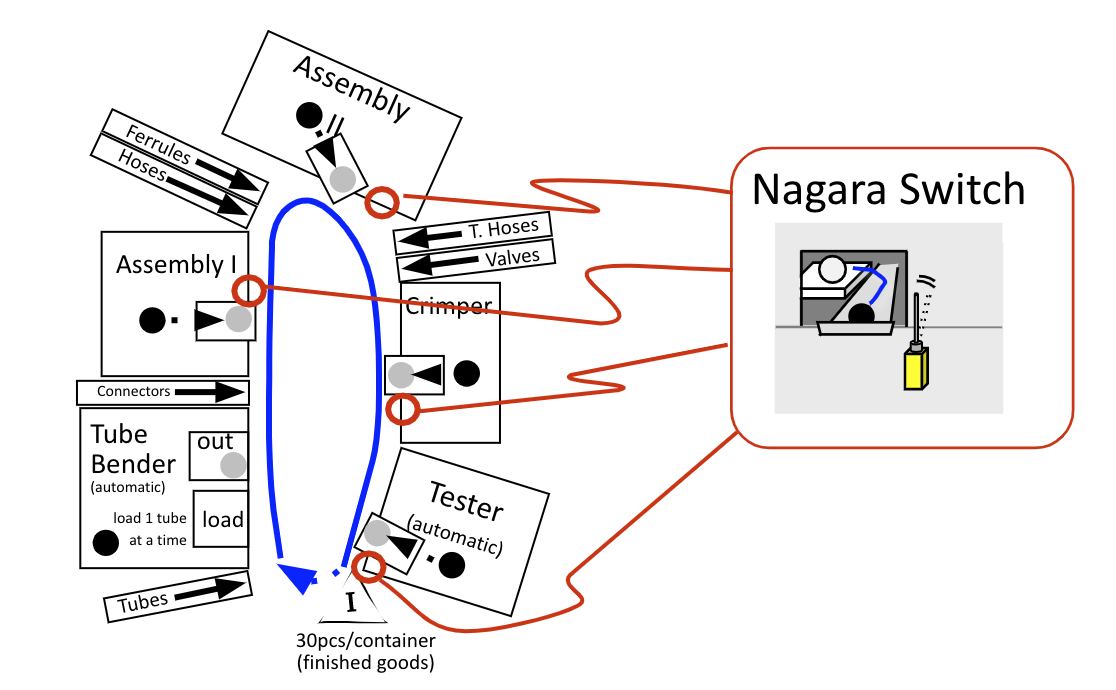

The Japanese term “Nagara” means carrying out two tasks simultaneously. The Nagara Switch – Harada-san himself never called it that, probably to prevent people from developing a technology-oriented bias – allows operators to start a machine cycle as easily and naturally as they can walk. As such, this device supports a team’s efforts to create continuous flow in multi-process operations. Today, Nagara Switches and similar job aids are commonly used in manufacturing operations. In the illustration below, you can see an example of Nagara Switch to create a better combination of operators and machines.

Chart-1: Applying Nagara Switches with auto-eject to the machines for a Chaku-Chaku operation in the example excerpted from Creating Continuous Flow.

In a recent Planet Lean article, John Shook referred to this device as a “Chaku Chaku Switch” (under the Nagara Switch name, it is now a product of OMRON in Japan). Whatever we decide to call it, it represented a highly effective device that paved the way for many improvements to be made in the interaction between man and machine – a critical piece of standardized work and showing of respect for people. There is no doubt this small, yet great device made a much bigger difference in the design of production lines and operations in automotive industries than Harada-san and his colleagues ever imagined. A good Chaku Chaku line simply cannot be created without utilizing Nagara Switches.

Photo-1: Nagara Switch TP70 of OMRON (Japan). Photo courtesy of OMRON.

It was also very important in the historical development of the “steps to jidoka”, one of the two pillars of the Toyota Production System. By the time Harada-san joined Toyota, some guidelines already existed for developing machines. By the late 1960s, these were compiled as “the Steps to Jidoka”.

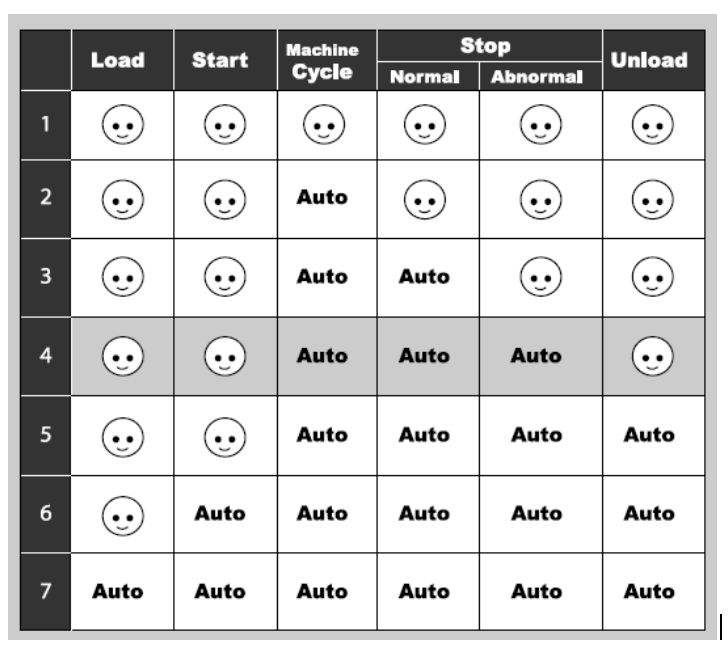

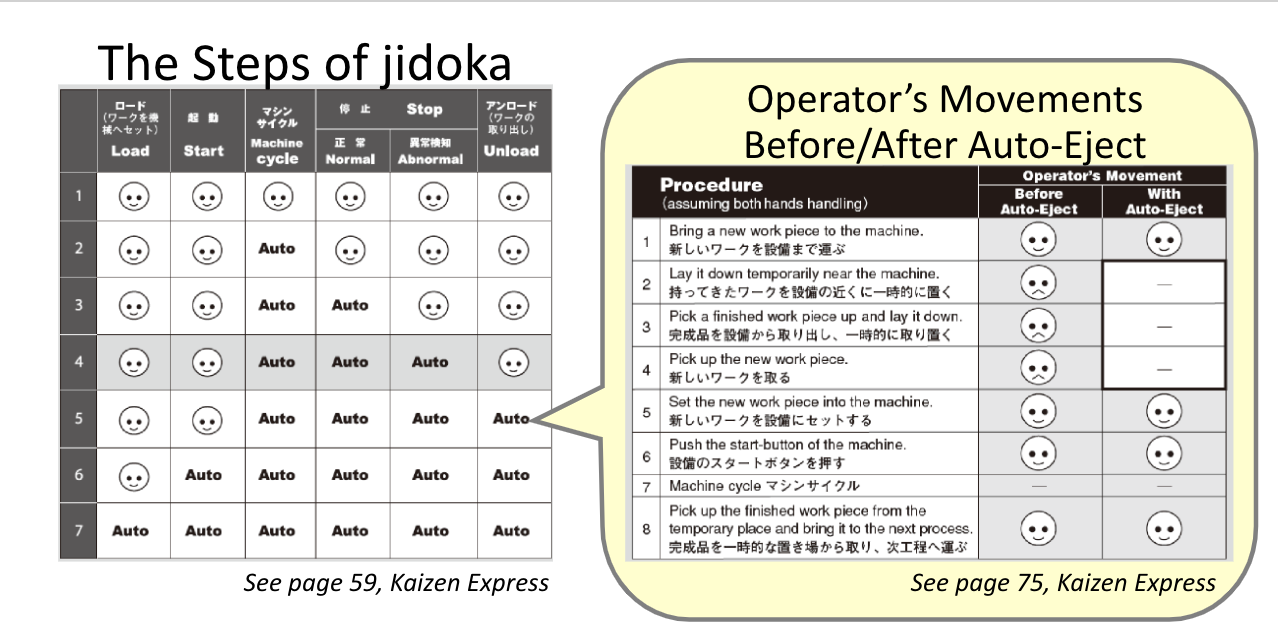

Chart-2: The Steps to Jidoka (See page 59, Kaizen Express)

In Step One (when there is no automation), all operations are performed manually. With Step Two, only the machine cycle is to be automated. Step Three calls for the machine to stop automatically when the cycle is completed, regardless of whether or not the conditions are normal or abnormal. In Step Four, we see the Toyota Way “in action”, with the development of machines that stop automatically every time something goes wrong (an abnormal condition). We typically refer to this machine function as “jidoka with a human touch” or “autonomation”.

But at this stage, the journey to better jidoka is still incomplete – the next step is to equip every machine with auto-eject functionality (parts are unloaded automatically).

According to Harada-san, the idea of the first five steps – from 100% manual to auto-eject – had already been established, if only loosely, when he was a young gemba gijutsu-in (manufacturing gemba engineer).

We can learn more on this in Lesson 12 from his book Management Lessons from Taiichi Ohno.

One day, when I was working in the house (the gemba office), the kaizen manager got a phone call from the shop floor saying, “Ohno-san wants you to come.” We got tense, “Oh, no; did we do something wrong again?” as we rushed to the place where Ohno-san was standing.

He was looking at the transmission machining line, and when we got there, he said, “Look at the movement of that operator. He is stopped every time to push that start button.” We were not too sure how to respond, as that was such an obvious thing and we had no idea where he was going with this finding.

Then Ohno-san told us, “He loads the part to the machine, walks a bit, stops, and then starts the machine cycle by strongly pushing the button. Can’t you develop a nice way for those operators to start the machine more easily when he is starting to walk to the next-step machine so he doesn’t have to stop his steps in every cycle any more to start the machine cycle?”

He continued, “Hmmmm, elevator buttons work well with a light finger touch. Can we employ such type of buttons? I guess they have to stop at that place to press the start button because they have to push hard…?”—meaning the current start button required a strong pressure.

Ohno-san of course knew that we had been using this type of start buttons for decades. The maintenance manager and I got a little relieved to see Ohno-san was simply pointing out a switch problem as we had been preparing ourselves for a tongue-lashing. Then we immediately started to develop a new machine starting device.

The kaizen team members had already been making things to improve gemba operations. It was their daily basic mission. And, during busy times they went and worked together with the operators in the production lines. We were expected to put that gemba operation experience to good use and fully utilize and make things easier for operators to their jobs.

After quick study, we decided the best course was to employ a limit switch, instead of the light-touch button for elevators which Ohno-san gave us as an example.

Now let’s go back to the steps to jidoka. TPS sensei at Toyota caution not to rush into the sixth and seventh steps – full-automation for the loading of parts, too – before installing effective auto-eject functionality and nagara operations (as they walk to the next step in the process, operators can easily start the machine cycle) to establish flow. Otherwise, the result will often be the acquisition of highly expensive and inflexible “automated” lines, which burden operators with excess movement, such as non-value-creating motions like stopping to push heavy start buttons – not to mention the burden and cost of dealing with inevitable breakdowns of equipment.

Chart-3: Free up your people from only serving machines with jJdoka. Nagara Switches can make an operator’s work (pushing the start button) in step 6 easier in a flow operation (Kaizen Express).

It is well known that jidoka has its roots in Sakichi Toyoda’s philosophy of work. The purpose of jidoka from the beginning was not just preventing machines from making defects, but also preventing people from unintentionally doing non-value-adding movements. Sakichi Toyoda said “Don’t make people slaves for machines. Instead, machines should work FOR people.” Even today we can learn this philosophy by studying the steps he went through in developing his automated looms. We can say that represents deep respect for the humanity of the people doing the value-creating work. Taiichi Ohno had learned much from Sakichi’s ideas and then added his own perspective for gemba application.

Harada-san himself acknowledged that in his younger days he and his colleagues, too, often failed to see how poor job design was forcing excess movement, walking, and struggle on workers. In his own words:

Material, or the product, should flow and people should be working in a flow, too. I think Ohno-san kept thinking all the time, which is why he was able to inspire his people to always try to get closer to a better flow.

….. Regrettably, however, we weren’t able to identify that problem, which forced operators to come to a stop in order to start the machine cycle, until Ohno-san pointed it out. But through this experience, we firmly determined to make improvements before Ohno-san could tell us, “Hey, this is a similar situation—fix it!”

Another day, we noticed an operator holding an impact wrench all the time during his work steps. We thought his hands to be freed up from holding a tool during all the steps, even in the unnecessary steps. Then we develop another switching device that allowed him to walk away once he had set the tool rightly on the nut.

We later came to call this type of automation as “one-touch automation.” It must be not only much cheaper than full automation, but also much simpler. Thanks to Ohno firing us up, we learned to see a lot more opportunities for this type of one-touch automation. This led us to make many, many similar improvements.

These insights still apply today, to any industry. It’s important for lean thinkers around the world to understand that the jidoka steps are powerful concepts for designing good work and that they illustrate the mindset and behaviors leaders should employ to support and develop their people as they strive to establish flow.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – If we see lean thinking as a paradigm, which we do, then we should be able to define a set of values this paradigm is built on. So, are there lean ethics? Michael Ballé identifies 10 undisputed lean values, plus one.

FEATURE - Britain’s National Audit Office looks at how well taxpayer money is spent, gaining invaluable insight into the use of lean management in central government.

FEATURE – ME Elecmetal in Chile applied Lean Product and Process Development to cut lead-times, boost collaboration, and build a sustainable system for innovation.

PROFILE – A commitment to learning and the humility to understand we never really know enough have led a Belgian mathematician to become a polyglot… and the CIO of Toyota Motor Europe.