Accelerating innovation with LPPD

FEATURE – ME Elecmetal in Chile applied Lean Product and Process Development to cut lead-times, boost collaboration, and build a sustainable system for innovation.

Words: Edison Collinao Robles

ME Elecmetal is a Chilean company specializing in integrated solutions for the mining industry, supplying grinding mill liners, wear parts, and smelting components for the mining industry. In recent years, we set a bold strategic goal: to double our sales within five years. However, achieving that kind of growth required more than just operational excellence in manufacturing; it required accelerating innovation by improving our product development process.

There were lots of improvement opportunities there. New products took too long to reach the market, resources were spread thin across multiple projects, and few new ideas made it into the development funnel each year. Engineering and commercial teams worked largely in silos, often reacting late to problems instead of anticipating them.

This situation prompted us to explore Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD)—with the help of Cristian Riveros of Lean Institute Chile and Nestor Gavilan of Barcelona-based Instituto Lean Management—as a framework to fundamentally rethink how we conceive, develop, and deliver new products. Such an initiative builds on top of the lean work we have been doing for the past eight years and is a reflection of two of our hoshin’s strategic A3s, which focus on developing innovative new products.

TOO SLOW TO MARKET

Before starting with LPPD, our product development lead-times stretched to as much as two years. Even smaller product variations could take months. For a business competing in the global mining market, characterized by rapid innovation cycles, this was a problem.

A clear example of this was the development of new feed chutes, the large components that channel ore into grinding mills, which represent a market worth $50 million. Due to our slow concept-to-proposal process, we only had a 5% share of it—a huge missed opportunity. In 2023, only three proposals for new feed chute projects were developed, and the hit rate of converting proposals into orders was about 50%.

We realized that to compete in this segment, we needed a systematic way to shorten development times, improve collaboration, and bring customer value to the center of the process.

BRINGING LEAN TO PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

The transformation began by teaching a cross-functional team the LPPD principles. Representatives from engineering, manufacturing, quality, and commercial areas worked together to “see” the current development process end to end.

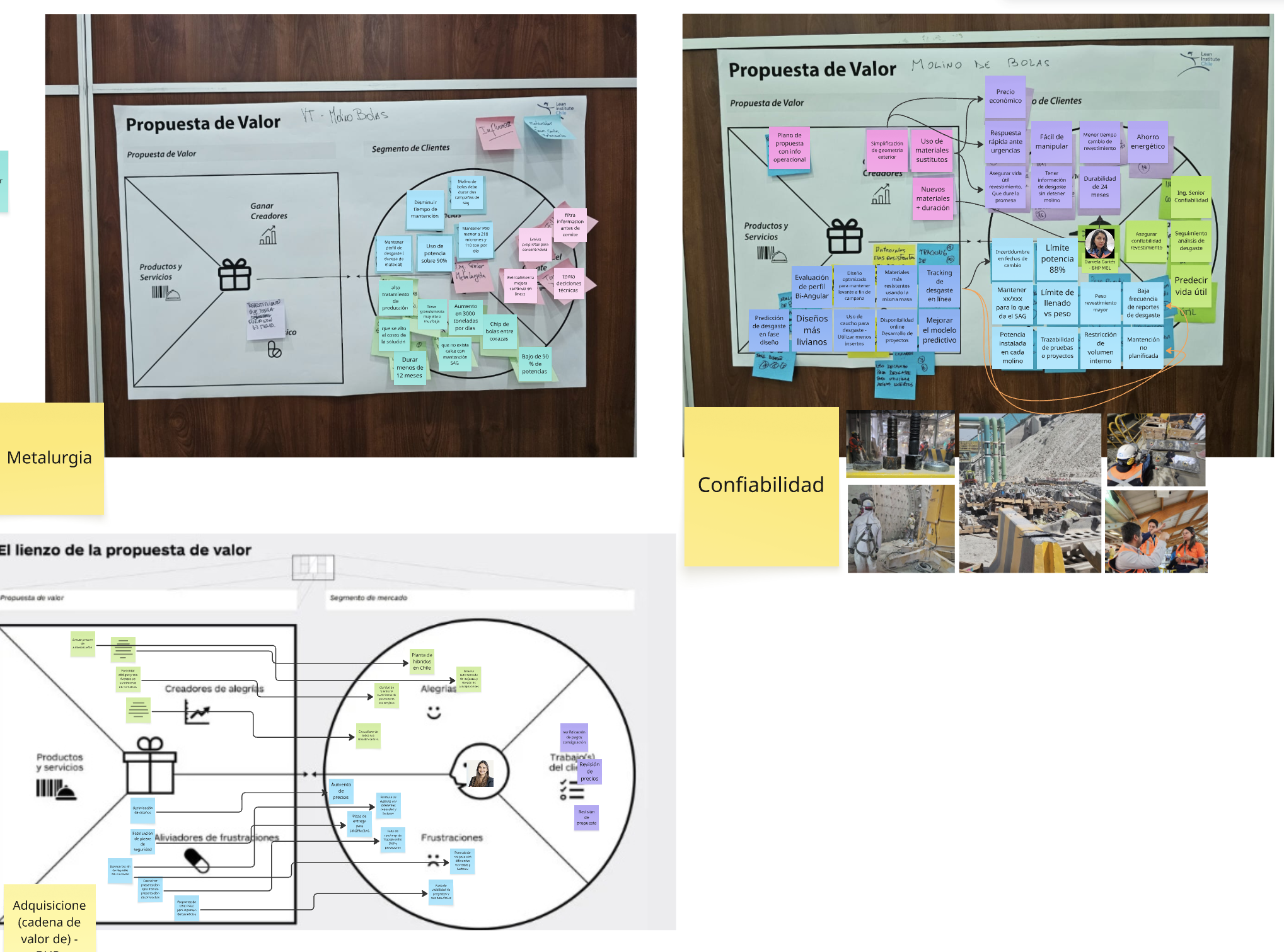

We began with customer understanding, conducting canvas persona exercises to identify key clients, their pain points, and what truly defined value in the products. To generate ideas, we introduced creative tools like Crazy 8, which helped multiply early-stage concepts. Critically, technicians were invited to the gemba to see real customer problems and identify potential, real solutions. Such direct contact with the gemba was a cultural shift for us in the engineering group, because prior to Lean, it was just a responsibility of the Sales Department.

The new approach was tested on the feed chutes project, where we developed several prototypes. The two initial ones failed, but through systematic experimentation and knowledge capture, we finally achieved a reliable design and a defined manufacturing method.

After identifying value as perceived by the customer, we focused on understanding product development as a process and on trying to generate flow wherever possible—which would allow to slash our time to market. For this, we did a value stream mapping (VSM) of the product development process, which revealed long delays caused by fragmented workflows, multiple manufacturing sources, and rework between departments. To address this, we designed a new process that emphasized a single, standardized approach to developing new products. To shorten lead-times, we introduced a subsystem supermarket (fed by R&D), from which the engineering team can now pull available technologies and solutions. This allowed us to clearly separate the research of new solutions, supported by set-based concurrent engineering (which has the added benefit of generating reusable knowledge based on the solutions that worked and those that didn’t), from the development itself and the applications of existing solutions.

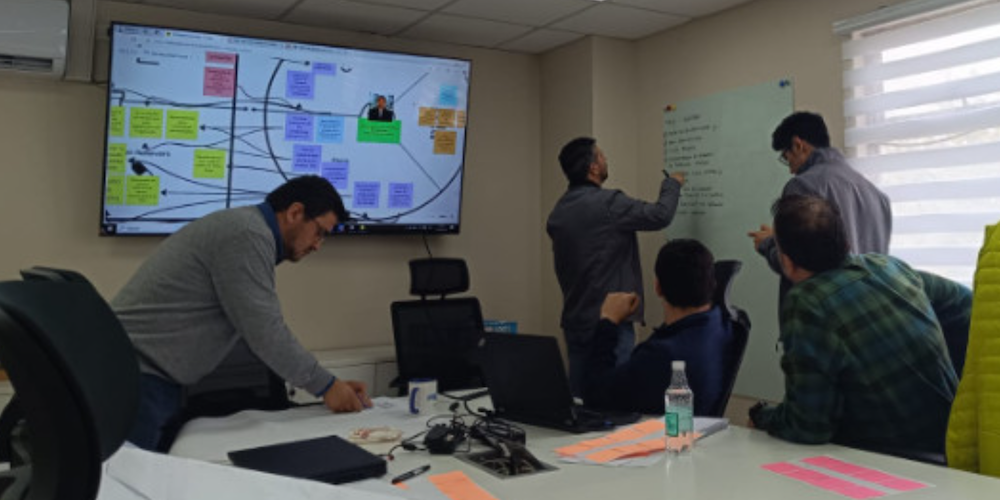

To bring visibility of the state of each project, improve communication and teamwork between different areas, and manage risk generated by the failure to comply with SLAs, we created an Obeya room, both digital (in Miro) and physical.

THE RESULTS

We were very happy with the outcome of our LPPD work. In one year, we increased our new product proposals from 3 to 15. The lead-time for generating design proposals fell from 100 days to around 50, and in some cases to just 15–20 days. We also entered a highly competitive client account long dominated by a rival and won our first order for a full set of feed chutes, using the new material and design developed under the LPPD approach.

Beyond measurable results, the process improved predictability and team collaboration. Engineers now have clearer visibility on delivery times and feel more confident about resource allocation. The multidisciplinary teamwork fostered by LPPD reduced information silos, allowing technical and commercial areas to work together more fluidly.

WHAT WE LEARNED, AND WHAT’S NEXT

Our experience with LPPD revealed not only successes but also challenges. We learned that concurrent development requires dedicated leaders for each subsystem—something not always easy when resources are scarce.

Perhaps the most important lesson was the realization that we need a dedicated area for product development and research—one that is not entangled in day-to-day operations. The daily work tends to focus on incremental improvements, so we need to organize innovation more strategically.

Building on the success of the feed chute project, we are now expanding the use of LPPD to other product families, such as mill liners and hybrid composite products (Polyfit). This year, we plan to continue standardizing our new product development process and to become better at consolidating learnings, for instance by introducing annual cycles of experimentation and knowledge capture. Only by making LPPD systematic can we make it a system for continuous innovation.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

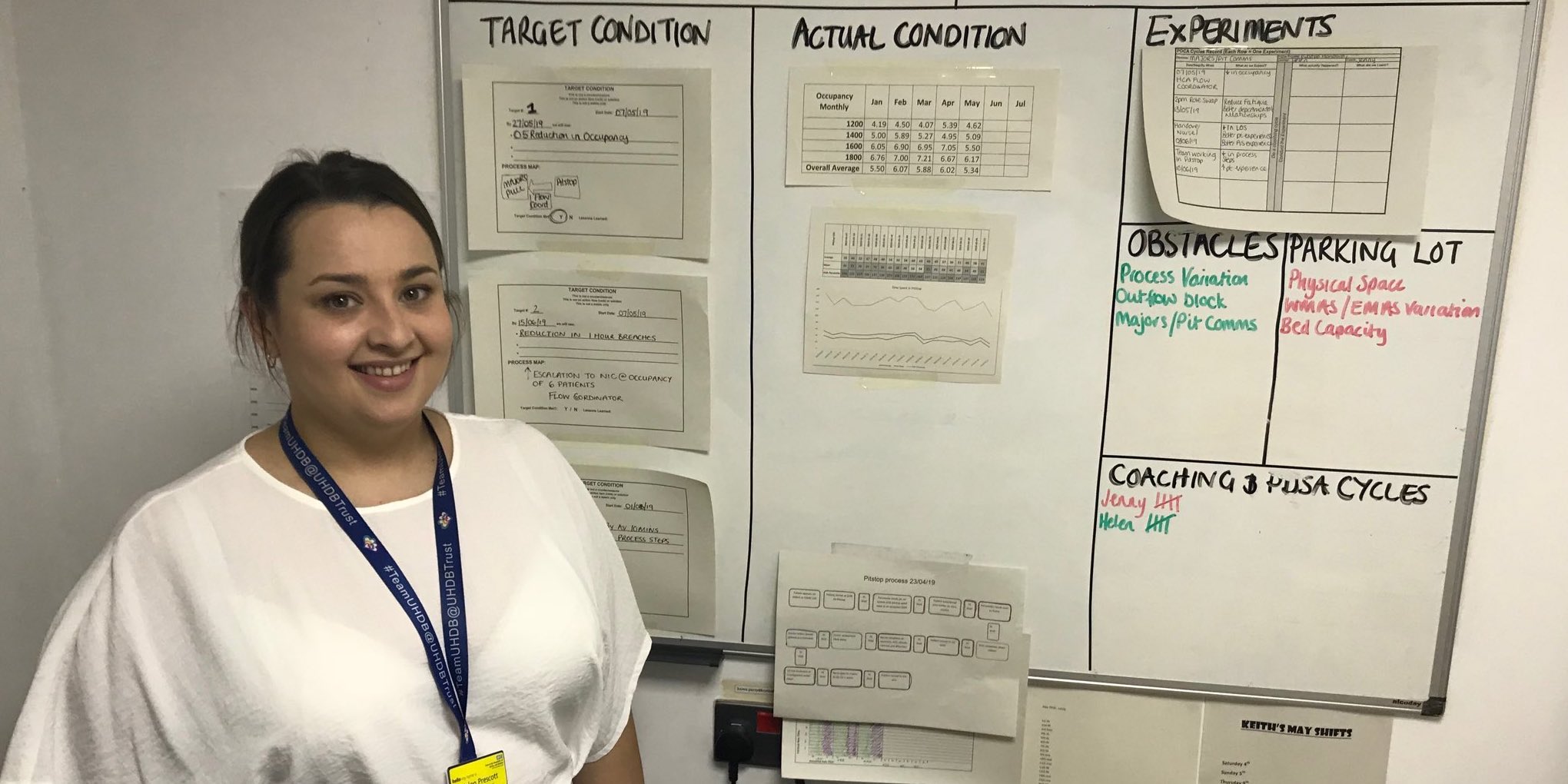

CASE STUDY – Starting with a series of pilot sites, the NHS is hoping to engage the Kata coaching approach to really spread an improvement culture to staff and patients.

INTERVIEW - Anton Ulanov is the CEO of one of the largest agricultural businesses in Russia. He talks with PL about the application of lean at Agroholding Kuban, discussing the wider challenges and opportunities for lean in agriculture.

FEATURE – There is more to logistics than an ancillary process that supports the rest of the company. But then, why do we never have a plan for it, like we do for manufacturing?

VIDEO INTERVIEW – This hotel in the Canary Islands is bringing lean to its Kitchen Department, hoping to streamline the process and provide a better service to diners.

Read more

INTERVIEW – Top leaders at Chilean company Elecmetal talk to us about how lean has transformed their role in the organization and how capability development is fuelling change.

CASE STUDY – This 104-year-old Chilean provider of integral solutions for the mining industry has turned to hoshin kanri to effectively connect everyone’s work with the overall business strategy.

FEATURE – Taiwan-based Machan International Co. manufactures sheet metal products, tool storage and medical trolleys, and smart energy storage cabinets. Last year, they turned to lean to improve their product development process.

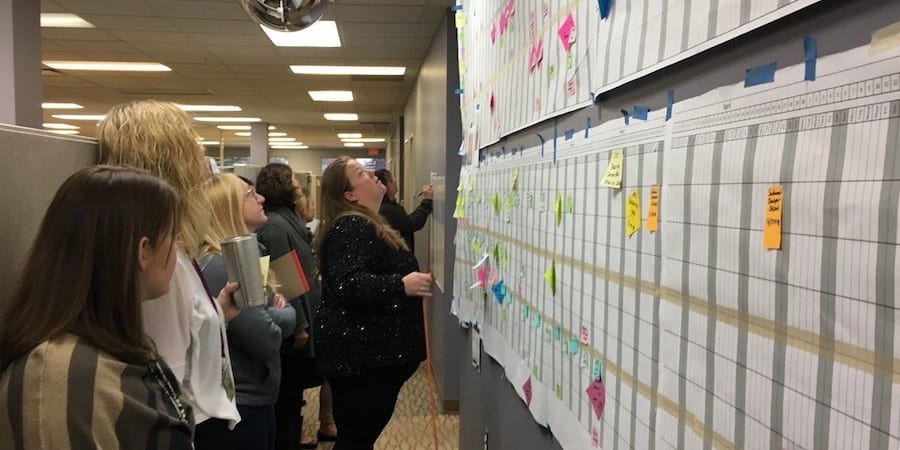

FEATURE – This article (and video) explains how Michigan Medicine applied lean product and process development tools and methods to their clinical processes. A powerful experiment.