Managing by metrics? Managers will game the numbers

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - Senior leadership must learn to understand the work if they are to move away from the mindless metrics that lead managers to "game" numbers or to shift responsibility on to other departments.

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

It's nearing the end of the second shift and the plant manager of a large factory is standing in the shipping lot. He's making sure trucks are in place to get all of the cargo loaded that needs to go out tonight. Is this a good example of an earnest leader who walks his talk to meet customer demand without fail? Well, not exactly.

To grasp the situation, you need one more fact: it's the last day of the quarter. The cargo must get through the gate by midnight to meet the plant's sales target (the manager's key metric), no matter the condition or destination of the goods. Otherwise the manager gets a reprimand from headquarters, no bonus, or worse. However, the production process has encountered problems and failed to produce the amount needed to meet the metric. So the manager is scouring the lot to find items previously produced but not ordered by customers because the plant had the parts to make them but lacked parts for other items actually desired. He will ship these items to the sales organization to meet his metric.

Doing this isn't a problem for the sales division because there is warehouse space available to store the items and the sales organization is not penalized for growing inventories. Its key metric is sales to end customers. So everyone will meet their target and make their bonus even as the total cost of running the company rises.

Welcome to the world of management by metrics, indeed by what I call mindless metrics.

Twenty-five years ago, when I first began to watch scenes like this, I thought that senior managers would soon come to their senses and stop judging lower-level managers on single-dimension, one-point-in-time metrics. Yet the scene I described above occurred in the spring of 2015 in a large and progressive multinational. How can this be?

I don't think the root cause is "bad" managers near the front lines. (Please see my column of April 30 on anchor draggers.) I've seen so many managers "gaming" metrics in so many companies in so many countries that I think the problem is situation rather than character. Otherwise good people (as I know from personal acquaintance that most of these managers are) are being put in impossible situations where their advancement, bonus, and even future employment depend on gaming their numbers because it is beyond their knowledge or power to actually improve their value creating process. So I understand why they do what they do. I probably would game the numbers too.

However, I don't think the higher-level managers devising the metrics for judging lower level managers are bad people either. All organizations have a need to assess their performance and it seems natural to pick a few simple measures – seemingly good things like on-time performance and sales – to judge how each lower-level manager is performing. But when the higher-level managers don't actually understand how the work can be improved to create more value, don't understand how value streams interact with each other, and don't know how to enable the managers below them to improve them, they fall back on the simple belief that requiring managers to achieve simple measures must somehow benefit the company. A lovely recent example is General Motors CEO Mary Barra's demand that post-bankruptcy GM managers make their numbers: "You made your plan; now hit your plan." Note that there is no mention of how to make the plan what the consequences of making the plan might be for other parts of the organization or customers, or what the barriers in the way might be. [Laura Colby, The Road to Power, Wiley, 2015, p. 122.]

How can we do better? How can we create what I will call mindful metrics that produce good managers and better companies?

We can start by acknowledging a simple fact: except through dumb luck (e.g., a shift in currency rates, a sudden spike in sales when a competitor can't deliver), it is impossible to improve the performance of an activity being judged by a metric without improving the value-creating work and removing the waste. So how a lower-level manager is going to improve the work and remove the waste and what this will mean for the rest of the organization are the key questions for the upper-level manager to ask when devising a metric and assessing performance.

If we believe good performance on a metric must be based on an improved value creating process, then a mindful metric must take account of the current performance of the process (value stream), the gap between current performance and needed performance (the improvement needed to please the customer and sustain the company), the root causes of the gap (which lie in the organization of the work), and the steps that need to be taken (the experiments that need to be tried) to close the gap by some point in the future, typically the end of a quarter or year. This, of course, sounds like a good use for an A3 and it is. Indeed, anytime I see a claim of achieving a metric – like the sales figures reported by the plant manager in the shipping lot – without support from an A3 showing the value creating process, the cause of the previous gap, and the experiments undertaken to close it, I am deeply suspicious.

With mindful metrics, each higher-level manager judges each lower-level manager on what he or she has done to improve and sustain the performance of their value streams by rethinking work and removing waste. Burden shifting to impose costs on the rest of the organization doesn't count! What's more, for the really proficient higher-level, lean manager precisely meeting the metric is not the point. The targets are based on a forecast in any case and unlikely to be "right" at the end of the reporting period. What is critically important, with dividends paid far into the future (and not measured by any quarterly metric), is to steadily improve and sustain every value-creating process being managed.

Organizations that do this will still have metrics. Everyone needs to know their gaps in creating value for customers and metrics can measures gaps. But the focus of higher and lower level managers will now be on the steps taken to improve value streams rather on achieving the metrics themselves. The challenge for those of us in the Lean Community is to coach higher-level managers in every organization so they can learn to see the work and the waste and can then coach their lower-level managers to improve the work and remove the waste, as measured by mindful metrics supported by A3s.

This article is also available in Hungarian here.

THE AUTHOR

Management expert James P. Womack, is the founder and senior advisor to the Lean Enterprise Institute. The intellectual basis for the Cambridge, MA-based Institute is described in a series of books and articles co-authored by Jim himself and Daniel Jones over the past 25 years. During the period 1975-1991, he was a full-time research scientist at MIT directing a series of comparative studies of world manufacturing practices. As research director of MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program, Jim led the research team that coined the term “lean production” to describe Toyota’s business system. He served as LEI’s chairman and CEO from 1997 until 2010 when he was succeeded by John Shook.

Read more

FEATURE ARTICLE - It is always fascinating to learn about the evolution of lean in other countries. This piece gives us the lowdown on the state of lean in Russia, a late adopter where interest is now growing fast in all sectors, from government to agriculture.

COLUMN - What does lean do for people in your organization? This column explores how their way of thinking changes as a culture of continuous improvement and problem solving takes root.

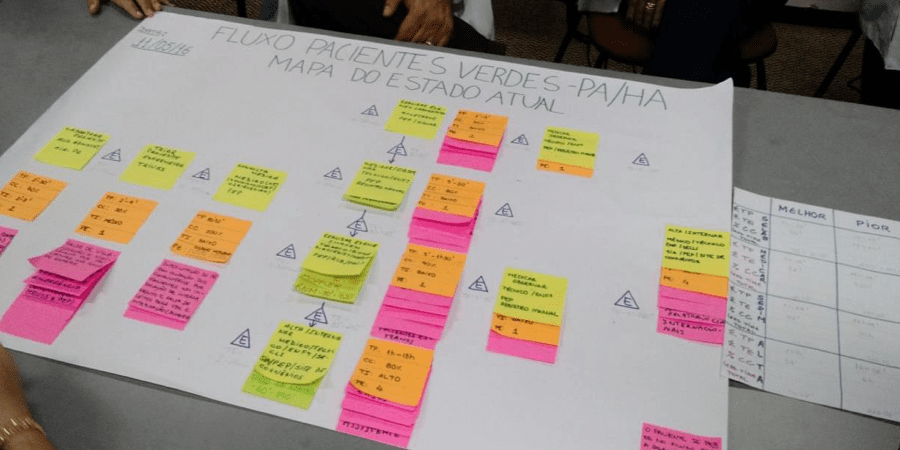

FEATURE – Long waiting times are bad for both patients and hospitals, but when we talk about heart attacks reducing them becomes a moral imperative. Here’s how Hospital Aliança in Brazil is doing it.

INTERVIEW – A 22-people veterinarian hospital in Barcelona has recently turned to lean thinking. We caught up with the owner to learn how things have changed six months into the journey.