Jim Womack on what is holding lean thinking back

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – On October 10, 1990 the book that introduced lean thinking to the world was published. Twenty-five years after Machine, one of the authors reflects on what the lean movement has achieved and on what is slowing it down.

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

October 10 marked the 25th anniversary of the publication of The Machine That Changed the World. This is the book Dan Jones, Dan Roos, and I wrote in 1990 to explain to a mass audience the new concept of lean production.

I believe Machine was the kick-off event for moving lean thinking out of the auto industry, out of Japan, and across the world. So I’ve found it natural to reflect this past week on what the global Lean Community has achieved in 25 years.

We’ve certainly written a lot of books in a lot of languages, spoken at a lot of conferences, and made the term “lean” accessible to most companies in most industries in most countries. I’ve just received a new book from an American farmer promoting “lean farming,” the first such effort I have seen, and it made me wonder if there is any significant and socially useful industry or activity we haven’t touched. (I once got a call from a Las Vegas casino asking about lean gambling. But I think gambling is pure muda, so I didn’t call back.)

We’ve also put a lot of lean, value-stream improvement tools into a lot of hands. And more recently, we have spread some very valuable management tools, notably hoshin planning, A3 analysis, and daily management (the latter to hold process improvement gains and to steadily improve.)

Yet with all of our efforts the world is only modestly leaner than it was when we started a quarter century ago. Why has yokoten – the central focus of this column -- been so difficult?

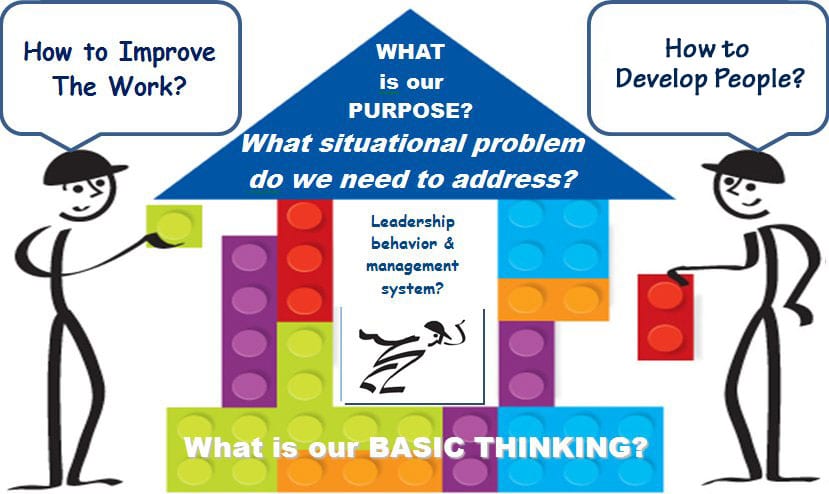

The hard part has not been the tools, technical or managerial. They always produce splendid results when pursued with adequate knowledge and constancy of purpose. The hard part, in my experience over many years, is the mindset of managers. (This is the foundation stone of John Shook’s Lean Transformation Framework, supporting purpose, process, and people.)

As we started our journey, I simply did not realize how completely we are all children of Frederick Taylor (best known for The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911) and Alfred Sloan (the General Motors Chairman who summarized his thinking in My Years with General Motors, 1964.) Together Taylor and Sloan created Modern Management and this mentality is what stands in the way of more rapid yokoten.

The key principles that I find so damaging for spread are:

- Taylor’s idea that improvement is done to value-creating front-line people by staff experts through programs. (Taylor himself was the first big-time consultant with teams and a comprehensive transformation program.)

- Sloan’s idea that line managers can be evaluated through metrics (often financial) imposed from the top without managers at any level actually needing to know anything about the value-creating work or its improvement. (“Make your numbers,” as this came to be known, is an idea alive and well at Volkswagen today as I wrote in my September column.)

Contrast these with a key management mindset propounded by Eiji Toyoda, the Toyota President and Chairman in the 1950s and 60s: All value is the end result of a horizontal process that runs across vertical organizations. So make line managers responsible for specific value streams and ask them to improve the value-creating work by means of endless experiments (PDCA in the context of A3 analysis.) Toyota managers call this “management by science” rather than Scientific Management.

To attack the manager mindset problem, I have recently been involved in an experiment in a company to create a model line for a value stream. Looked at one way, the objective is to dramatically cut lead-time, space, human effort, defects and rework. (In short to “show what good looks like” to the whole organization.) And I’m sure that many readers have thought of this activity in this way as they implemented model lines.

But the actual objective of this exercise from my perspective is to expose all of the contradictions in management mindsets that will prevent even the most successful model line from being sustained:

- Line managers completely disconnected from the work of the value stream. (Instead, they spend their time managing exceptions – things gone wrong – and upper-levels of managers, with their scoreboards of many metrics.)

- Process “coaches” from the continuous improvement department who end up doing the improvement work rather than asking the line managers about their value stream and how they plan to improve it.

- Senior managers trying to manage with contradictory metrics that measure vertical departments, functions, and business units rather than the horizontal value stream (the only organizational unit the customer cares about).

Without countermeasures, these modern management mindsets will quickly turn any lean model line back into a mass production line, a dreary process I have witnessed many times. My hypothesis is that the best countermeasure will focus directly on creating different, lean mindsets for the management team at all levels.

I recommend experiments of this type for every lean practitioner – line manager, staff coach, or external consultant. Please do create a model line for at least one product family – a wonderful thing in itself. But use this exercise as a method for diagnosing the problems of modern management in your organization and showing what lean management looks like instead.

I think this is the next leap ahead for yokoten and I hope many practitioners will give it a try. However, I’m not worried about the future of the lean thinking if this takes some time and includes some false starts. Here’s the reason:

There is no shortage of waste in the world. But there is a marked shortage of value. Lean mindsets and practices in combination provide the best-known way to convert waste into value. So we may be at it for a while, but lean will win in the end as modern managers gradually tire of easier expedients that don’t work or are replaced by managers with lean mindsets.

2040 will mark the 50th anniversary of Machine and I’m thinking I should stick around for the second 25 years. (I’ll only be 92 and both Dr. Deming and Eiji Toyoda lived longer.) What I’m hoping to see then? A management mindset across the world that is lean (that’s “post-modern management,” if you will) where lean tools and methods are consistently and sustainably applied by lean line managers to reduce waste in every value-creating activity. That will be yokoten indeed.

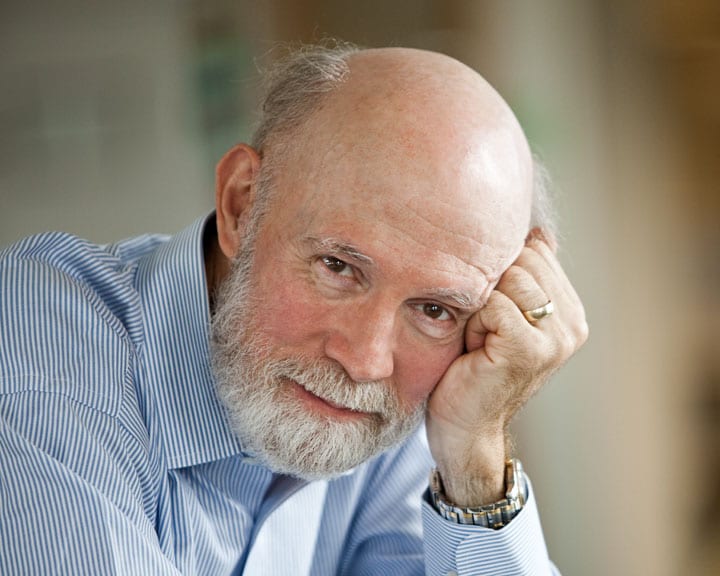

THE AUTHOR

Management expert James P. Womack, is the founder and senior advisor to the Lean Enterprise Institute. The intellectual basis for the Cambridge, MA-based Institute is described in a series of books and articles co-authored by Jim himself and Daniel Jones over the past 25 years. During the period 1975-1991, he was a full-time research scientist at MIT directing a series of comparative studies of world manufacturing practices. As research director of MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program, Jim led the research team that coined the term “lean production” to describe Toyota’s business system. He served as LEI’s chairman and CEO from 1997 until 2010 when he was succeeded by John Shook.

Read more

FEATURE – A bad management system generates distortions that represent the root cause of many of the problems experienced by organizations.

COLUMN – As individuals, how do we relate to the Lean Community? And what motivates us to stubbornly continue down the improvement path, often against all odds?

FEATURE – This article applauds the tenacity of women leaders and seeks to illustrate how they motivate others to take on the sustainability challenge through lean practices.

CASE STUDY – Italian company El.Co. leveraged digitalization to overcome some key limitations of its manual kanban system while maintaining its pull system intact.