Fertile ground for lean seeds

FEATURE – Lean Institute Brasil is running pioneering lean experiments in agriculture. The authors reflect on the challenges of transforming traditional farming culture and the opportunities lean affords.

Words: José Roberto Ferro, Ricardo Itikawa and Bruno Battaglia - Lean Institute Brasil.

Graphs and illustrations: Nêio Mustafa, Lean Institute Brasil

Every day, at sunrise, farm workers all over Brazil group around a “capataz” to find out what their job will be for the day. On any given day, the work of “peões” might entail anything from gathering cattle for vaccination to planting seeds for the new harvest, fixing a fence to maneuvering a giant picking machine.

The word capataz comes from the Latin “caput” (head). He – it is always a he – is the person responsible for organizing and controlling the activities of a farm and representing the voice and authority of the owner (who typically doesn’t live in the farm and therefore feels the need to hire someone to take care of business on a day-to-day basis). His role is to distribute the work by giving orders and telling people what to do. The workers – most of them with very little education, often times totally illiterate – follow directions and do what is expected of them. For the capataz, loyalty to the owner prevails over competence and rationality: even in the face of people who have received formal training, they approach to management is still old-school and lacking basic scientific principles.

It is in this environment that we at Lean Institute Brasil are starting our first lean experiments. We are bringing lean thinking to farms in the states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul. Both areas are considered centers of excellence for the integrated cultures of soybeans and corn and for cattle. Family-owned properties here vary in size from 2,500 to 5,500 hectares of cultivated area and raise between 4,000 to 5,000 heads of cattle.

In this article, we will share what we have learnt so far about lean thinking applied to agriculture.

HOW TO START THE TRANSFORMATION OF AN AGRIBUSINESS

With our first projects, we weren’t sure where to start and how. We immediately noticed that the tendency in the industry is to blame nature for every bad harvest – too much (or too little) rain, too many pests, and other factors. Of course, nature plays a key role in the performance of an agricultural business. However, there had to be more.

Once we asked, for example, for information on machinery availability, we weren’t able to get any. When we searched for the cost structure and financial performance, we were able to gather very little reliable data. While there are plenty of publicly-available metrics in the sector, these were often not tracked in the farms we engaged with. Moreover, whenever we discussed what the problems, basic standards, needs or possible targets were, the answers we’d often receive were “We don’t know” or “We don’t have that information”.

These elements betray a lack of parameters to track performance metrics and key business performance and show how primitive the management system in the agricultural sector is. (Effort has focused on technological advances rather than improving management systems.) Performance is mainly assessed “in retrospect”, after the production cycle has been completed. For example, to gauge how efficient a crop was agrobusinesses typically count the sacks produced. In the same way, the determination of how successful the raising of cattle was happens after the animals are sold. There would ways to monitor the situation as it unfolds – for instance, checking the state of the plants or how fast cattle are gaining weight – but such actions are normally not taken in a structured way. Hence, gaps can be tackled.

Unfortunately, the majority of business owners in the sector believe there is nothing that can be done to control cost internally. Because agricultural prices are mainly determined by the international commodities market and vary according to many factors (mostly beyond the control of individual farmers), the prevailing mentality seems to be that “if the nature helps, we will be successful”. Of course, government subsidies play a role in propping up businesses at times of low profitability.

In a situation in which things that happen on any specific day or hour can only be loosely and vaguely connected to the overall performance of a business, we set out to identify the best approach to support these businesses. Should we do an A3 to focus on key problems? This sounded like a good idea, but to define the topic or problem to be solved was a nightmare. We even tried to define some vague problem or goal, but understanding scientific thinking and overcoming the lack of basic data proved to be challenging endeavors for the participants in this exercise. Root cause analysis, target definition, etc., simply appeared to be beyond their capabilities. We even tried a VSM exercise to identify systemic connections and problems in the flow, but too was of little use. We didn’t give up.

IDENTIFYING AND UNDERSTANDING THE PRODUCTION CYCLES

We then decided to understand the work and the production cycles more deeply, in order to plan the activities at a macro level and cascade them down to define a weekly agenda and a daily management routine as a means to improve performance.

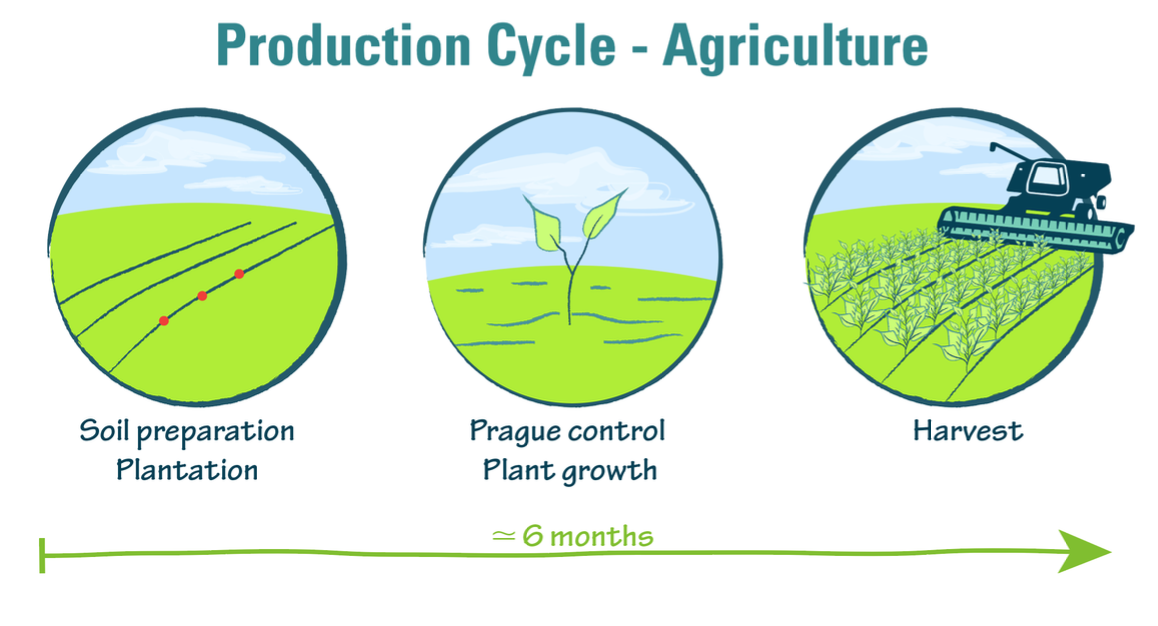

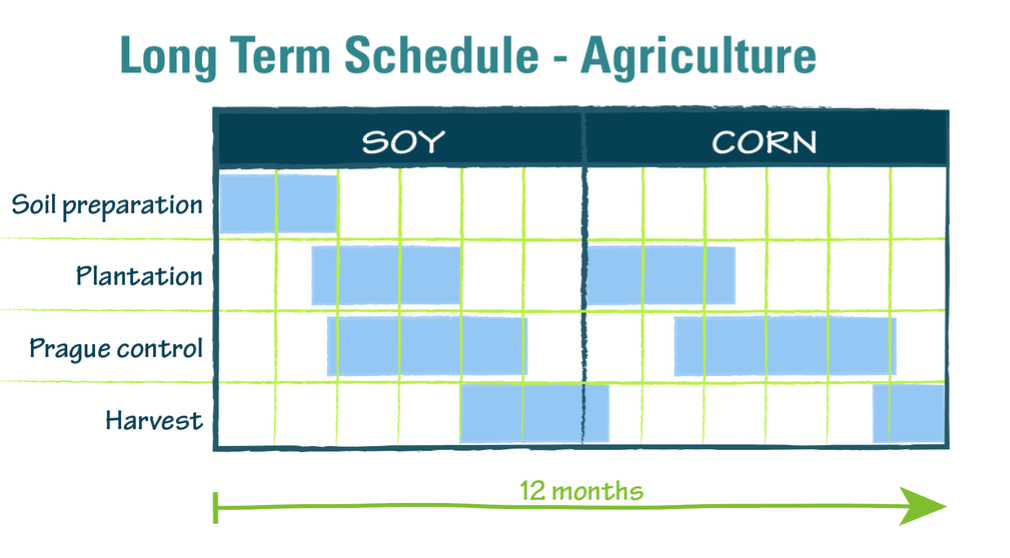

By production cycle, we mean the main stages of the production process. In agriculture, for instance, these would be: soil preparation, seeding, plague control and harvest. For soybean and corn, this cycle takes around six months and takes place on the same soil.

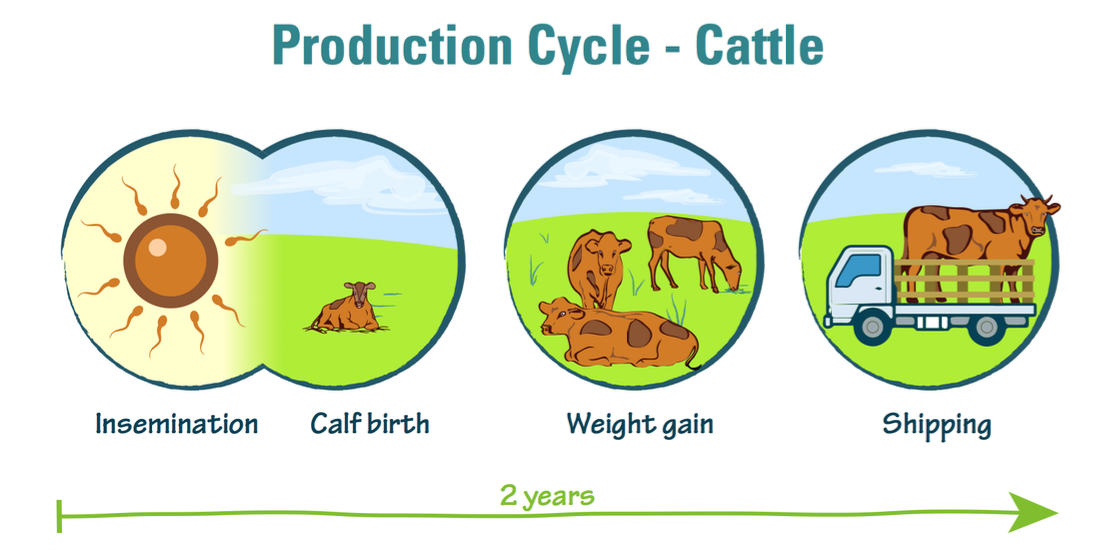

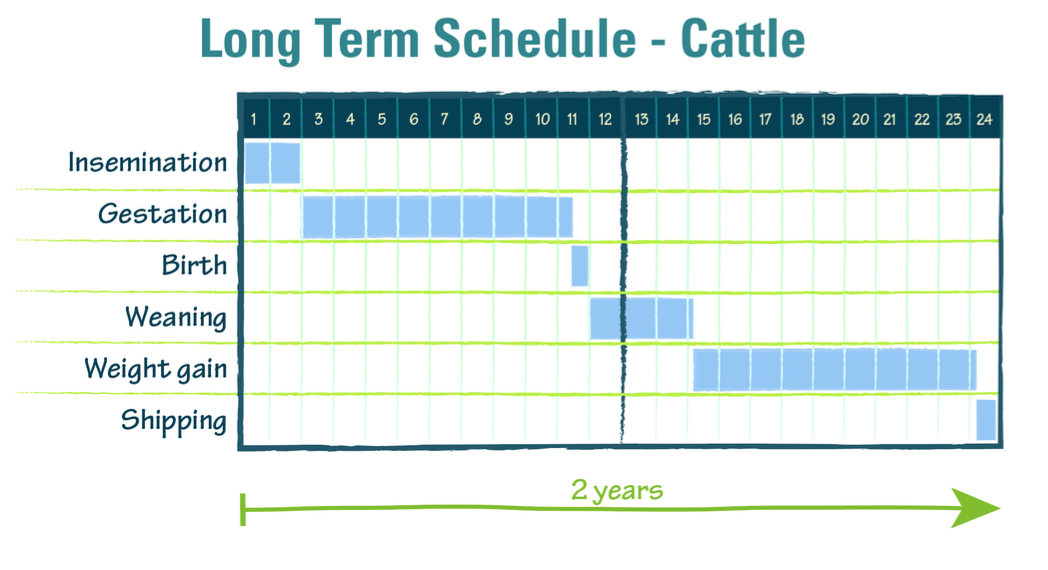

The cycle for livestock is very different, usually around two years from insemination and calf birth, through to weight gain and shipping to customers.

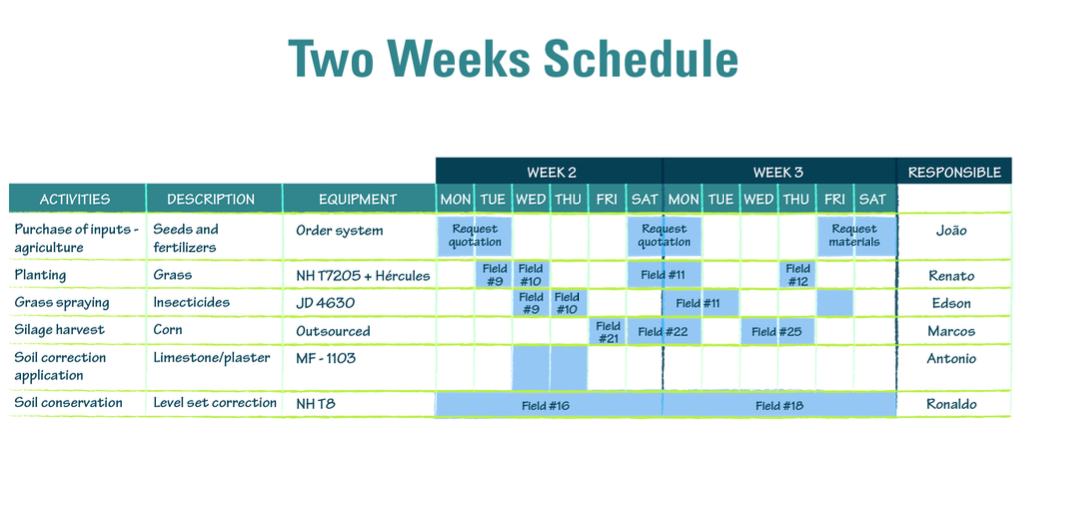

After this, we decided to focus on the job to be done in a two-week time frame and daily (from Monday to Saturday). We tried to enable the people doing today’s job to develop a better idea of what is in each day activities bundles and what the near future will bring.

To do so, we helped them to divide the work and allocated jobs to each individual on each day, based on the current stage of the production cycle.

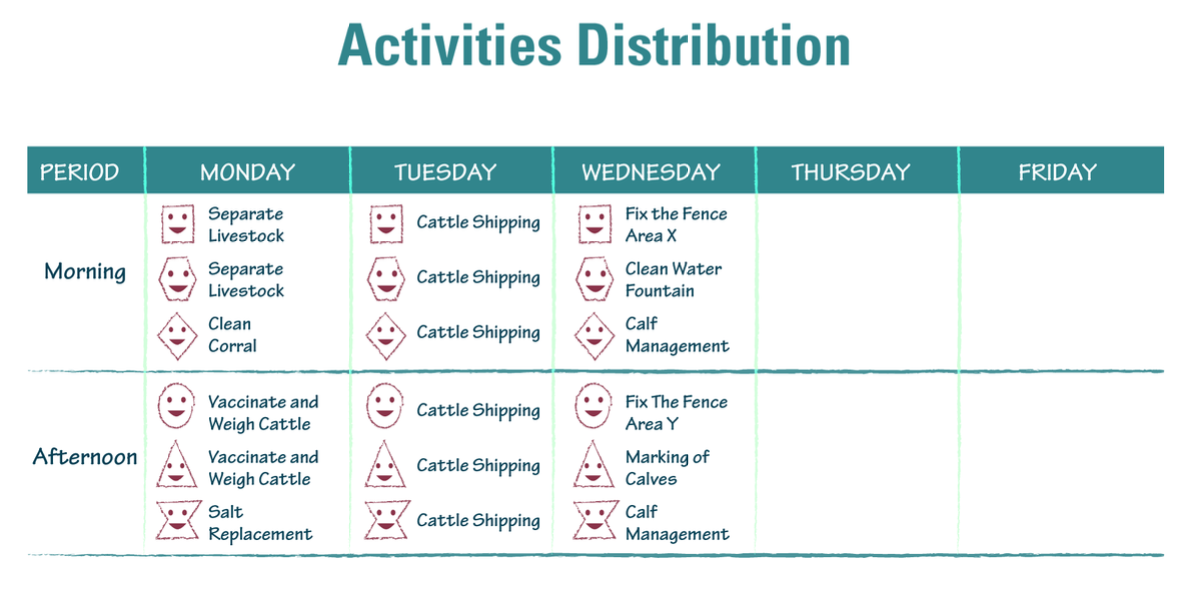

Let’s take a look at the cattle activities, for example. On any specific day, the teams will be divided according to the activities required.

This planning process was made visual in a board by which the team began to meet every day before work started, typically between 5 and 6 AM.

STARTING THE DAILY MANAGEMENT

Defining daily activities allowed for a more structured way to establish the work to be done, which is now displayed visually and transparently for the whole team on a daily management board. In principle, each worker would be able to identify his activity (assigned by the supervisor) on the board, which explains the work to be done, highlights challenges, and so on.

To truly empower people, we suggested the meeting take place with the whole team standing and individual workers taking turns by the board, where they read out loud the task they are assigned. This was, of course, not easy, as many of the workers proved very shy and reluctant to speak in public. Some of them even had a hard time reading – literacy levels are low in rural areas of Mato Grosso.

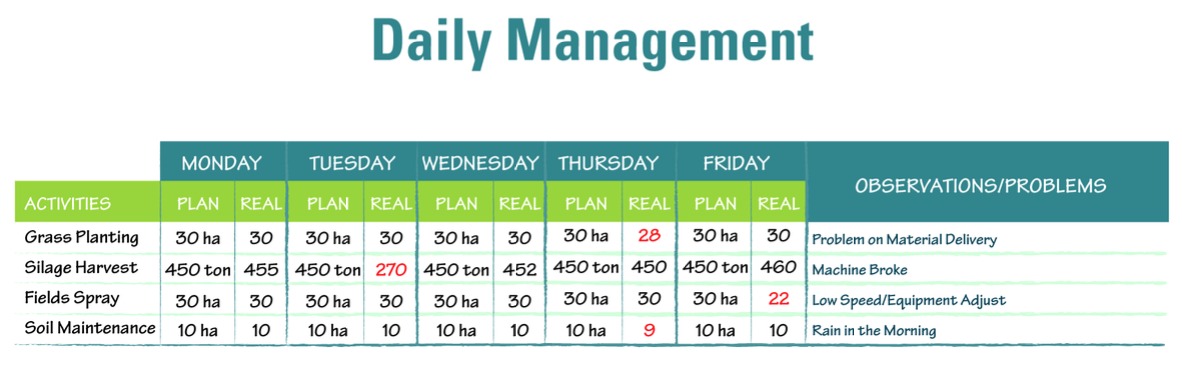

Initial difficulties were related to the lack of basic standards. Activities were usually very vaguely defined, often without quantitative targets. For example, if the job of the day was to plant the seeds, there was no clarity on how many slots of land. To define some basic work standards and job descriptions, we helped the team creating simple videos.

As those initial huddles started to happen, the first benefits appeared: workers began to feel more empowered and committed; leaders were able to make adjustments during the day; activities could even be shuffled over the week to counteract the interference of weather conditions on the daily work. Bringing objectivity to the definition of the work and clarity on who does what, the daily management board increased teamwork and reduced the workers’ dependence on role of the capataz/supervisor. The board is now running the show and defining what needs to be done.

We found it difficult to get workers to use the board to highlight the “reds” – instances in which the expected results weren’t achieved – as they didn’t see the need to unearth and flag up problems in order to correct them.

Over time, the daily huddles evolved to incorporate machinery (and not just activities) – a key resource in this business – and new visual boards and even A3s were created. One, for example, focused on machinery utilization planning.

Daily management has provided many additional benefits to the agrobusinesses we have worked with. For example, during the crop harvest, identifying the expected daily results and comparing them with the real outcomes created the opportunities to intervene on machinery operations such as picking, shelling etc. Since the harvest process was outsourced (to a third party paid per hectare), there was no incentive to be effective and improve volume produced by hectare – a key metric in a farm.

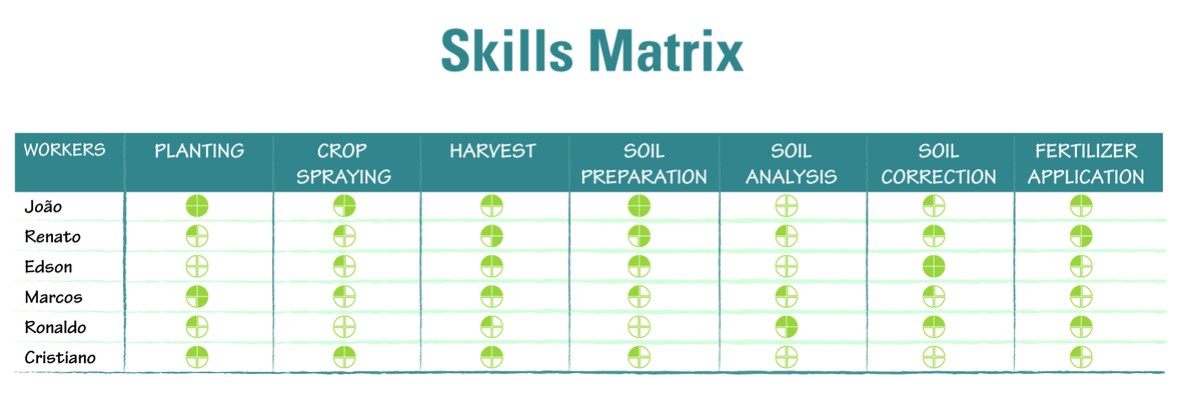

We also assisted the team in the creation of a skills matrix, which is used to identify who is qualified to do what job. This tool is very useful in the event of adjustments in the work distribution.

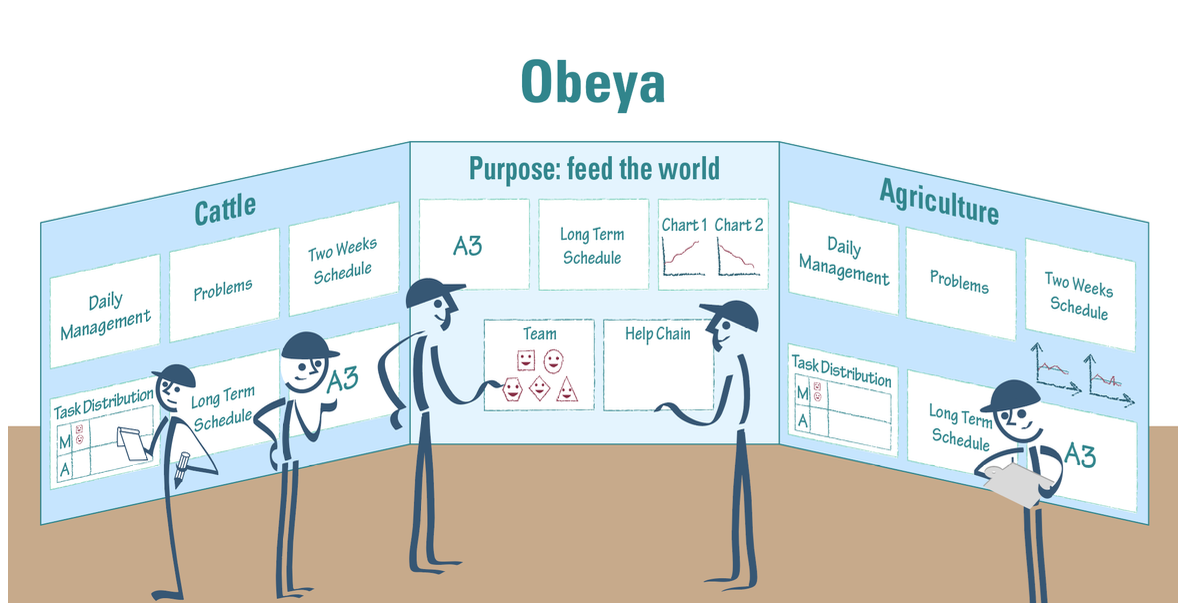

THE NEXT STEP: AN OBEYA

As the companies progressed on their lean journey, they started to focus on more and more elements of the work – machines, people, raw materials, etc – which called for a more elaborate and complete way of setting and monitoring goals: an Obeya.

The first obeyas created featured the following elements: a purpose definition (“Feeding the world”), a two-year schedule; current crop activities (beginning to end); a layout of the land divided into slots; machinery and equipment utilization planning and schedule; a schedule for fixing roads and fences; the definition of basic work standards; a labor skills matrix; A3s developed by the teams.

Having such information readily available during the daily huddles helps to clarify all the connections between the different pieces of the work and makes it easier to adjust when external conditions (like weather) change. Critically, it also helped in getting people even more involved. With so many different jobs taking place across a farm, having aligning and mobilizing everyone towards the same goals proved to be a powerful mechanism to help people understand they can play an active role in ensuring the success of the business (as opposed to just accepting what Mother Nature decided to throw at them). negative impact that complacency was having on the performance.

The businesses have begun to measure results during the different stages of production (traditionally, the performance of the farm is only known after the crops or the cattle are sold).

As the teams continue to progress, we are expecting them to see and capture positive results in terms of: reduction of losses during crop plantation and harvest; better use of machinery and equipment; faster weight gain for cattle with less cost; on-time beginning of activities; and better maneuvering during adverse weather.

IN CONCLUSION

In this initial phase, we focused on daily management because of its potential to improve the management system, change leadership behaviors and generate better results. However, there are many more gaps we are hoping to address as our learning continue – starting with the creation of a better process for identifying emerging problems more easily.

We also plan to help the organizations to implement a more decentralized decision-making process that empowers workers on the farm. Being the ones involved in the daily work, they are better placed to make important decisions for the farm – from what seeds to plant to when to sell cattle or the need of fertilizer – than the owner (often sitting in an office thousands of kilometers away), a supplier of raw materials or a cooperative providing part-time support to the farm.

The initial experiments we have run in agriculture here in Brazil prove that lean thinking and practice can be extremely useful to transform farming. Indeed, we believe the agricultural sector is extremely fertile ground for the application of lean principles. We are honored to have planted the first seeds.

Thanks to Adroaldo Taguti from Copasul (Cooperativa Agricola Sul Matogrossense), Navirai – MS, for providing the opportunity to work with Fazenda Santa Marta, owned by Claudio Sabino, and Fazenda 3 Irmãos owned by Julio Jacintho. And to Miguel Sastre for giving us the chance to work in his Fazenda São Miguel in Terra Nova - MT. Thanks also to Egidio Tsuji, Tharles Francesco, Pedro Lopes, Perivaldo Carvalho, Wagner Zampiva, Dario Freitas, Marcio Carneiro, Murilo Saraiva, Ronaldo Palma, João de Jesus, Luiz Augusto, Cassiano, Giovani and others for their contribution, effort and enthusiasm in planting the lean seeds.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – We are used to approaching strategic thinking as if our organization was in a position of stability and dominance. What if we started to look at it as creating better deals with all parties involved?

FEATURE – Effectively applying just-in-time and achieving flow is impossible without leveling production first. Yet, most companies seem to think this is impossible because demand is so variable… but is it really?

GETTING TO KNOW US – We sit for a chat with the President of Institut Lean France. Not only has ILF created a vibrant community of lean CEOs in France; it also launched one of the most innovative lean events out there.

FEATURE – How did lean healthcare organizations respond to the most critical stage of the epidemic? We asked three hospitals in Catalonia and Toledo to share their experience.