The visual management lessons learned at Thales Group

FEATURE – How do you ensure that lean visual management doesn’t become anything more than a way to reassure the boss, rather than foster a learning and problem solving culture?

Words: Cécile Roche, Lean & Agile Director, Thales Group

A few years ago, when the company launched a new approach to its lean transformation, I was determined to avoid the hurdles we had encountered until then. Our previous efforts – mainly focused on waste reduction – had been led by a team of internal consultants, who used value stream mapping to optimize processes. We ran a lot of workshops and projects, and identified a lot of potential savings, but ultimately we were able to sustain very few results and saw no real change in everybody’s daily working life. To quote Shakespeare, it was “much ado about nothing.”

Having learned from that initial experience – and knowing that lean is first of all a way to develop people using the scientific approach – I decided to kick off our second attempt by introducing visual management. This would be one of the pillars of our new strategy – we call it Short Interval Management, which consists of three main elements: visual management itself, to see problems; problem solving to develop people; and regular routines (daily meetings) to keep this learning system running.

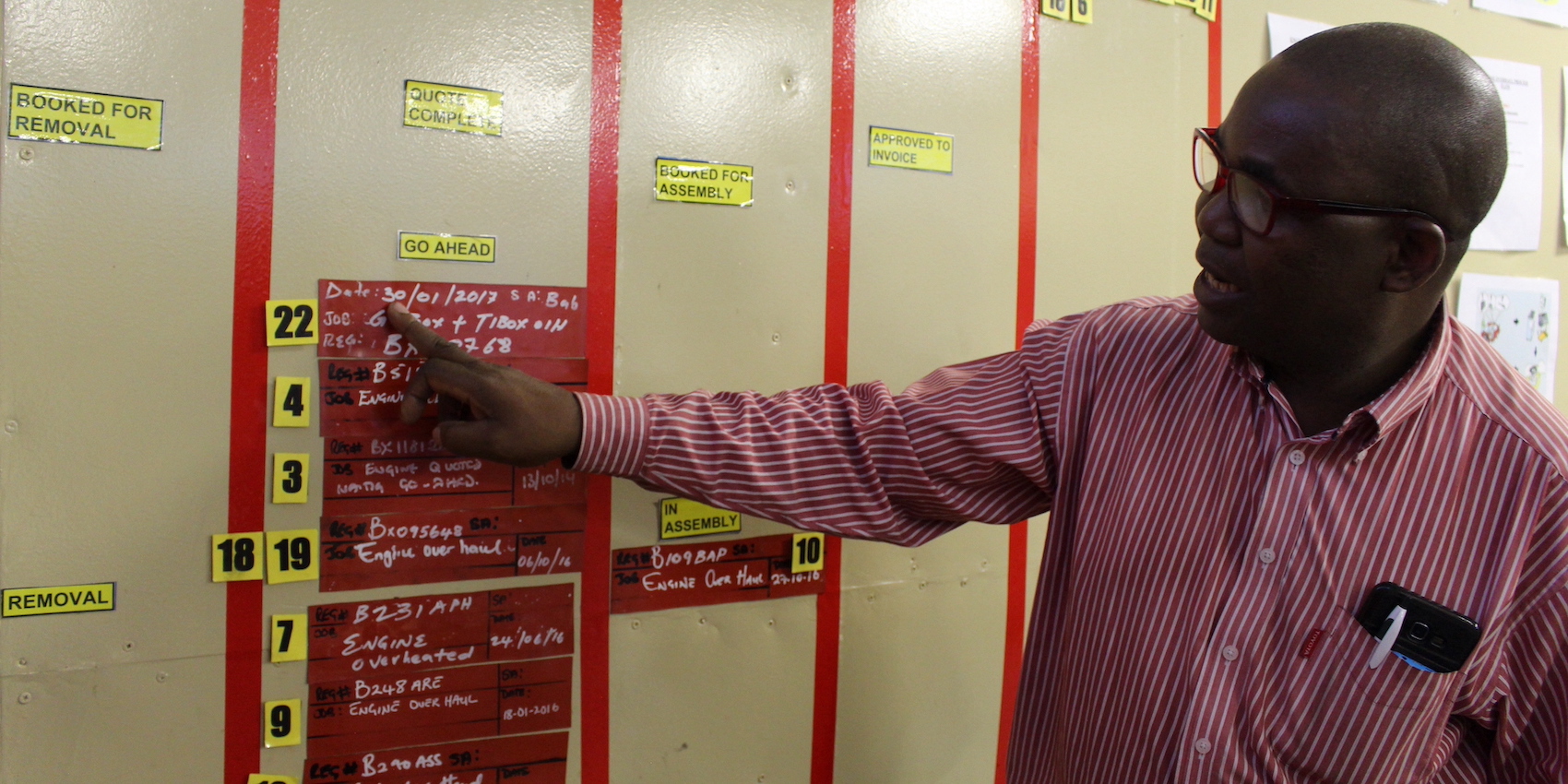

Visual management – and we insisted a lot on this in all our training and coaching sessions – was not heavily standardized, except for a couple of very important items: each team in the manufacturing department would have to identify and display both their key performance indicators (critical to learn how to distinguish between OK or Not OK work) and their work-in-progress (WIP). It was also highly recommended that they provide operators with a space on the boards to leave their comments.

This new approach immediately proved successful: teams were clearly very happy to discuss the work with their managers at least once a day and to share the problems they were encountering. On their part, managers were happy to have a clear overview of what work was in progress and to be able to identify issues in real time. All seemed to be going well but, as everybody knows, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and before too long we started to experience a number of problems with our visual boards:

- First of all, the unlimited creativity and imagination of our teams resulted in several very large work-in-progress boards that soon became too complex for the uninitiated to read and understand.

- Another problem was with the part of the boards devoted to operator comments: all too often, they were replaced by action plans. Managers were of course reassured to see that action being taken to fix identified problems (even when it was as obvious as “ordering a new component” for a problem identified as “missing part”), but whenever they asked the operators to share their opinion on the causes of the problem it was clear they couldn’t. Nobody was learning anything.

- The performance field was hardly ever completed. Most times, it was replaced by a very classical set of indicators – cost, delivery time and quality – that were systematically documented in “rear-view mirror mode” (well after they were supposed to be recorded).

- One team even came up with a leaflet they used to describe problems, which ended up turning the daily meeting into an occasion to distribute problems (with the manager always received the longest list).

Sadly, our Short Interval Management approach had led to everything we had wanted to avoid:

- a command-and-control system rather than a learning system (its purpose being to reassure the manager, not to encourage people to express their opinion);

- a system for action rather than for reflection;

- a system to remove responsibility rather than one that develops people’s autonomy;

- and a system for problem management rather than problem solving.

The creativity of our people had not been tapped into properly, and as a result the system had allowed them to use it to create tools (the boards) but not to improve processes and products (their daily job). Unsurprisingly, whenever we asked them to change the boards, they were very reluctant.

WHAT TO DO THEN?

The way to get around our difficulties was to increase our focus on systematically pursuing continuous levelled pull flow (we call it CLPF) in the Production Department, which had a double effect on visual management: it simplified and decentralized it.

Because CLPF is in itself a visual system – with its kanban cards, heijunka box, continuous flow, and so on – we could greatly simplify our visual boards. CLPF doesn’t need too many boards: it already (and naturally) informs you in real time of the state of the work and on the problems that are occurring.

Since we boosted our CLPF efforts, we also saw our problem-solving activities decentralize and our teams become more and more autonomous. Every opinion counts now, and every day our visual boards are getting a little bit more connected to each of our employees. We expect all of them to share their opinion and contribute through their comments, and more of them do.

Our recent pivot towards pull flow also helped us to clarify the roles within the organization: managers are responsible for the implementation of the boards, while people are responsible for their content (we are trying to unleash their creativity to run better processes and create better products, not to blindly use lean tools).

There is no doubt that the most important lesson we have learned is that, as soon as you propose a new system for improvement, there is a risk that people will fall in love with the system and forget about the improvements it aims to achieve. In such a scenario, visual management becomes a tool to reassure managers – in a command-and-control fashion – instead of a way to develop people’s autonomy and critical thinking.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – Sharon Visser shares her leader’s standard work from when she ran the Ngami car dealership and encourages us to use what we see at gemba to shape our own.

THE TOOLS CORNER – In this new series, we go back to basics, offering a guide on how to implement some of the most important lean tools and explaining why they are so clever. First up, Kanban.

PROFILE – Lean is spreading like wildfire across the Catalonian healthcare sector, following a do-it-yourself model unique to this part of the world. Our editor met one of the practitioners who are making it happen.

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – The author explores how France’s Lean community evolved through gemba practice, kanban-driven engagement, communities of practice, and a flywheel model turning shared learning into momentum.