The power of lean planning

FEATURE – A Dutch transmission system operator is using Lean Planning – built around the Last Planner System – to better manage its complex infrastructure projects.

Words: Michiel Bakhuizen, Planner Onshore; Emile Brentjens, Financial Project Leader Offshore; Eugene Meuwszen, Tactical Buyer Offshore; Inge Oortgiesen, Project Leader Onshore; and Ewald van Dorst, Project Leader Offshore, TenneT - The Netherlands

TenneT is a transmission system operator responsible for Holland’s and part of Germany’s high-voltage electricity grid and its connections to neighboring countries. We are in charge of very large and complex projects, but often struggle to ensure there is enough awareness across the organization on how they are progressing.

That’s why we introduced lean planning at TenneT, an approach inspired by Last Planner System (a staple of lean construction). Our management team was a bit reluctant to use lean planning at first but changed their minds when they found out our subcontractors regularly did. We even went to see a subcontractor in Leiden and witnessed one of their stand-up meetings. Shortly thereafter, a session was organized to try and get Tendering and Engineering to join forces and introduced both teams to Lean Thinking.

We also decided to run a pilot project, for which we chose to focus on a large infrastructure project: the construction of a 70-kilometer power line in the south of Holland (part of it overhead, part of it underground) that will transport offshore energy to the mainland. Much of our work entails writing documents, determining legal and technical requirements, and obtain licenses to build before we can start with the tendering. It’s a lot of coordination, because to build even a simple construction like a transmission tower you need to engage with several subcontractors (some to lay the foundations for the tower, some to build the tower, some to set up the road to reach the location, some to lay the cables, and so on).

This is a long-term project, scheduled for completion in 2029. The first three years will be dedicated to design, engineering, procurement, tendering, and reaching agreements with the local authorities and landowners along the corridor (to obtain the necessary licenses). In many ways, the most challenging part of the work is the obtainment of the licenses: disputes with local government over the towers already caused the project to be restarted once. Having to build such a large corridor within an existing infrastructure is complicated, and not knowing how long each negotiation with local authorities or private citizens will take makes the process even harder. This means it’s really important for TenneT to minimize waste and waiting time internally, to create something of a buffer in case complications arise in obtaining a license (something that’s often out of our control).

A successful lean planning approach consists of three fully integrated steps:

- The overall planning of 1- to 2-year milestones and deliverables per phase;

- Six-month planning of products per month, based on a Master Document List (MDL) or Work Breakdown Structure (WBS);

- Weekly planning of committed activities per responsible role.

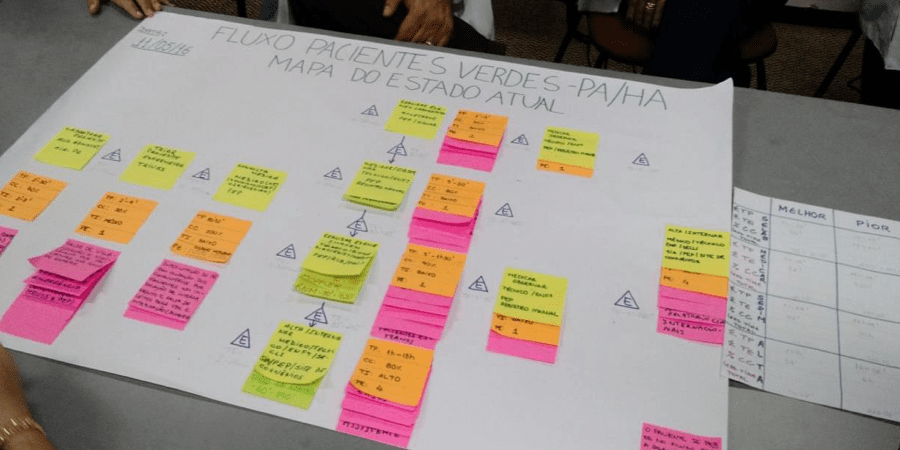

In practical terms, this entailed the introduction of a large board that would be used by different departments to map activities and progress, which were broken down into blocks of six months. When a project is 10 years long, people struggle to keep their eyes on the ball – which is why dividing it in smaller deliverables makes sense. Our teams needed a way to get better visibility of our activities every week, understand the details of the work, the deadlines and, in general, what everyone was accountable for and working on at any one time. Lean planning immediately brought a better definition of roles and responsibilities and created more support and accountability between our teams.

Meeting regularly in front of the boards helped us to see things in a different way. Learning to prioritize made our people’s lives easier: they could now talk to each other about what they needed from their colleagues to continue with their work. For example, the bulky reports the Engineering team has to put together for each project (which is often hundreds of pages long) are something many other functions depend on; however, not every function needs all chapters of the document at once. Discussions in front of the board highlighted many instances in which only three or four chapters (out of 50, sometimes) were necessary, which meant the Engineering team could focus on those first. It’s the lean idea of not overproducing, but to work on exactly what’s needed by the next step in the process when it is needed.

Indeed, everybody is more aware of the daily activities now and there is a general sense of being more in control of our process. At first, we brought all departments together for the meetings, but communication proved very challenging and, in the end, we decided that each (sub) project should have its own board and meetings instead.

And yet, there was (and still is) resistance to lean planning at the beginning. Most people didn’t like it. Some even called the boards the “Wall of Shame”. Not only was there a certain reluctance to commit to deadlines (with an unpredictable process like Licensing, for example, people wanted to retain their flexibility), but also a common lack of understanding of what benefits might derive from using lean planning. To some, the advantages were clear, but others just didn’t see what was in it for them.

One-to-one coaching was very important here. Listening to our people’s fears and doubts, asking them lots of questions, engaging them in conversations and helping them to see the advantages of lean planning went a long way in getting them to warm up to the new approach.

Eventually, people realized that they had to start working with one another more closely and that lean planning could help them to get there by understanding each other’s work and commit to each other’s deadlines. In time, visualizing dependencies and synergies between different departments made goals more attainable and the lead-times of deliverables started to get shorter. When, during a standard meeting it becomes clear that someone has not been able to complete a piece of work, it is now a common practice to try and understand why together. We have become more aware of how our work impacts our colleagues’.

Lean planning was also applied to Offshore projects at TenneT. Our Offshore Department had three months to prepare the documents for two tender processes to identify and hire the contractors that would carry out two seabed investigations to determine soil conditions and the safety of the areas where underwater cables had to be placed. Ours seas are littered with many underwater objects such as debris, fishnets, wrecks, boulders and Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) we don’t even know are there and these objects can of course represent a huge risk for vessels installing cables underneath the seabed. – that’s why ensuring there is no risk is a precondition for any offshore project to go ahead.

Not completing the investigation would have resulted in the whole project being delayed by at least several months, to huge cost for TenneT. For such tenders, we have to prepare supporting documentation to help us identify the best contractor for the job. These are typically multiple extensive that, as you would expect, require a lot of work.

Tenders are executed during the initiation phase of a project, when the project team is being recruited. A tender team consists of the new members and experts from multiple departments (for example, cable experts from the Asset Management, experts on Operations and Maintenance from the Grid Service Operation department, Offshore experts from the cross-border Offshore department, legal counselors from the Legal department and buyers from the Procurement department). In the meantime, these experts are also involved in other projects.

Lean planning proved very helpful in getting all the experts together and in supporting them as they worked to deliver all the necessary tender documents in such a short timeframe. During the lean sessions we held, it became clear to all the experts involved that there are a lot of interdependencies among the different areas. It helped the team members to understand the interdependencies to reach our final goals. Lean planning helped to determine which document should get priority and what knowledge from what experts was required and when. It also helped the experts to better coordinate the many activities and projects they were involved in, which resulted in all the necessary tender documentation being ready in time for the publication of the tenders.

Thanks to lean planning, not only were they able to publish the tenders within a few months, but they were also able to reduce the amount of documents enormously (they went from several hundreds of pages to a few dozens).

THE COACH COMMENTS

by Serge Simons, Lean Coach, Lean Management Instituut

The two projects discussed above couldn’t have been more different. The power line project is long-term – this specific one will be two years long, for the licensing, ten if we consider the whole value stream – whereas the offshore project discussed needed a quick turnaround. The fact that lean planning led to successful outcomes in both projects proves how adaptable a system it is.

As a matter of fact, I have used it in several environments in the past, from Schiphol Airport (where we leveraged the engineering phase to refurbish the F-gate in four and a half instead of nine months) to Nyenrode University (here it helped us to set up a new program within the curriculum), at Miele (where we used it to set up a marketing event at Lowlands, a musical festival) and MerckSharp&Dohme (where we set up 3 pilot projects to prepare the implementation of a new fire alarm system in multiple production facilities).

This approach facilitates planning and communication between different functions within a value stream. The nods to the Last Planner System are clear: this method, developed by Professor Glenn Ballard and widely used in the lean construction world, was designed to help different trades on a construction site to effectively collaborate, hand over work, and commit to each other's deadlines.

I made the point of introducing a Learning Log to both projects at TenneT. This way, if anyone was late with their commitments, we could write down the reason why. What that showed us was that in most cases, delays appeared because people were waiting for their colleagues to complete their piece of work. It was an eye opener for the teams, which eventually convinced them that it was necessary to find an alternative approach.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – How Lærdal Medical was able to enthusiastically restart its lean journey with help of a good old-fashioned Kaizen Week.

FEATURE – Long waiting times are bad for both patients and hospitals, but when we talk about heart attacks reducing them becomes a moral imperative. Here’s how Hospital Aliança in Brazil is doing it.

FEATURE – With the help of Lean Thinking, this Ukrainian producer of stainless steel pipes is retaining its competitive position against larger players in the market.

CASE STUDY – Over the past few years, DBS Bank in Singapore has undergone an extraordinary turnaround inspired by lean. Here, the COO explains how the company has become the world's "best digital bank".