Making RFS possible - the lean implementation at UCC Coffee

FEATURE – Repetitive flexible supply is a very effective method to level production scheduling, but as a FMCG company in the Netherlands found out, sometimes a number of conditions must be met before the approach becomes viable.

Words: Mark Brugmans, Production Manager, UCC Coffee, with Arnoud Hoogeveen and Wiebe Nijdam, Lean Management Instituut

Every year, UCC Coffee manufactures 23 million kilograms of roasted coffee for the Benelux market. We produce ground coffee and package it in vacuum packs and pods for retailers, providing them with the end product as it appears on their shelves.

We started to implement lean principles in earnest a couple of years ago after top management asked us to find efficiencies in our processes to ultimately achieve better financial results. We knew there was a lot of potential for improvement in our processes, and our general manager seemed very enthusiastic about the results that lean thinking could bring us in terms of efficiency and profitability.

Over the course of a one-week lean training session (which we offered as part of our efforts to develop our people), we drew an A3 outlining the potential we saw for our organization and were finally able to understand what our current state looked like and identify specific opportunities for improvement. While there was a lot in the value chain that could be done better, we decided to focus on three main issues:

- Understanding and reducing complexity in the number of SKUs;

- Understanding demand;

- Creating reliability in production.

With these three prerequisites met, we thought UCC would be able to come up with a better scheduling plan, one that would allow us to level production, stabilize our processes and eventually improve our overall (operational and financial) performance.

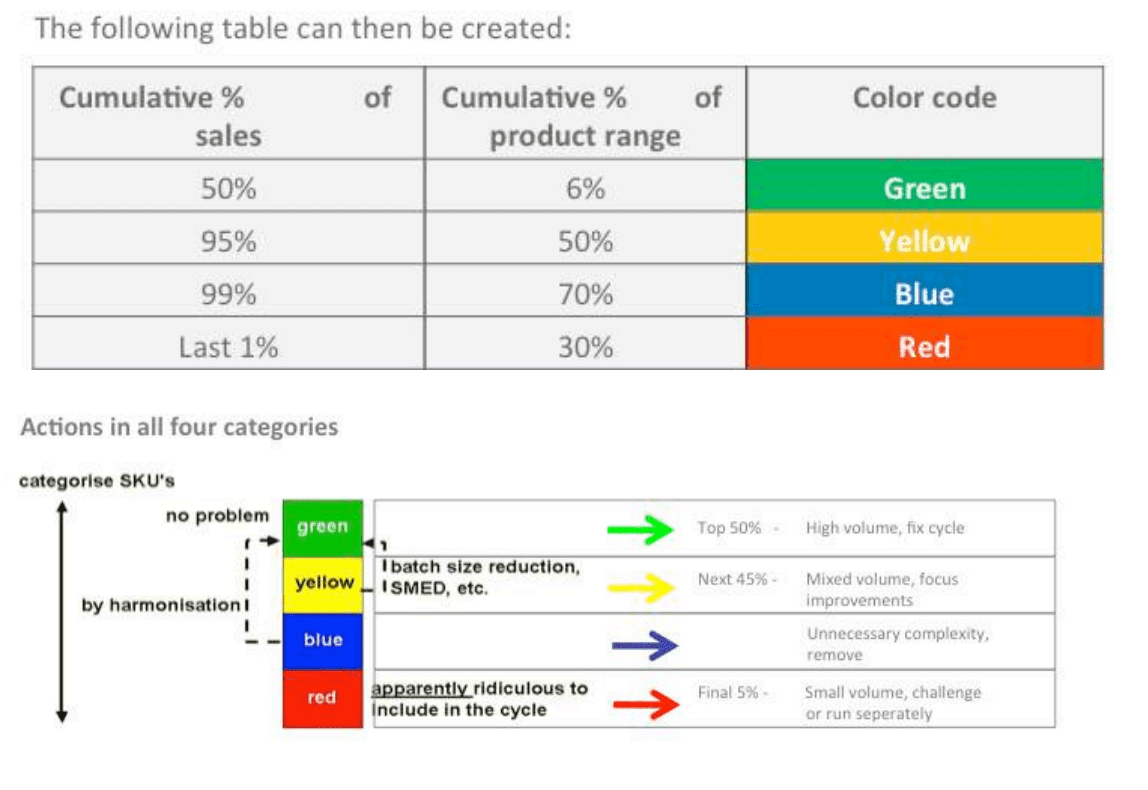

Getting scheduling right is a well-known issue for manufacturing firms, many of which find an answer in repetitive flexible supply (RFS), an approach based on the idea that making the products with the largest volumes in the same sequence at the same time every week will greatly help to level production. The research carried out by Ian Glenday – the creator of RFS – shows that, typically, 6% of a company’s products represent 50% of the volume it produces.

Repetitive flexible supply is indeed an extremely powerful approach, but we are convinced that it can only work if certain conditions are met. We believed that if RFS were to work at UCC, we’d first have to reduce the number of SKUs (we have a lot, and not enough machines), really understand customer demand and make our machines more reliable.

So we decided to run an experiment, with the help of Lean Management Instituut, and try a slightly different approach to RFS planning, which I will explain in this article in the hope to inspire other organizations facing similar challenges.

We formed different project teams, to involve as many people as possible from across the organization: finance was there to help us understand how we were performing; sales would support us in the reduction of the number of SKUs; while operators would be instrumental in stabilizing production and improving OEE.

More than anything, we wanted people to get on board and did our best to engage them in teamwork. We encouraged them to constantly talk to each other and to come up with their own ideas, rather than passively accepting ours as the way to go.

HOW THE EXPERIMENT UNFOLDED

Reducing complexity

The first part of our experiment consisted in reducing complexity. When we started, UCC had over 1,200 SKUs, many of which had very low volumes. We weren’t even sure the company was making any money out of those!

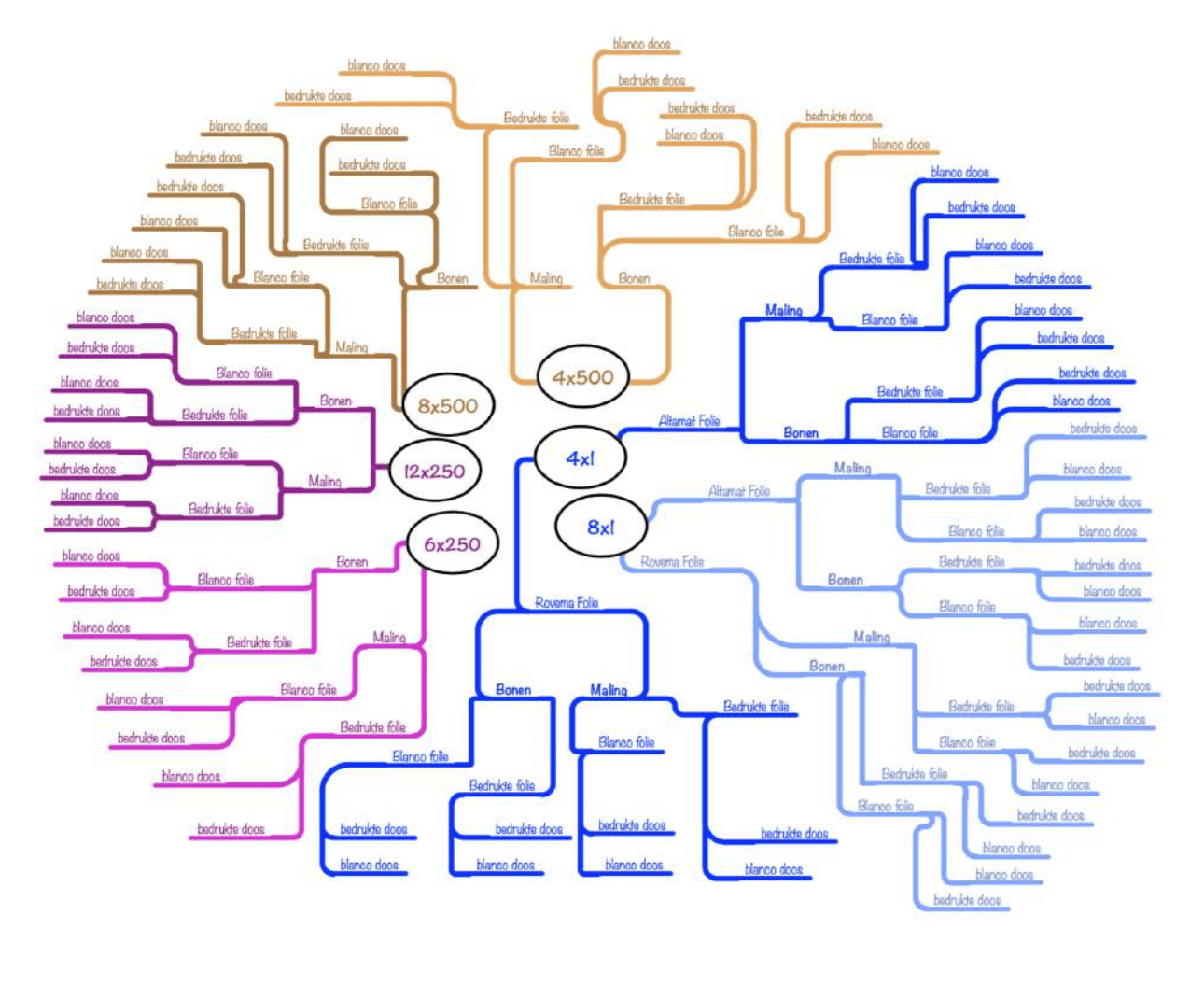

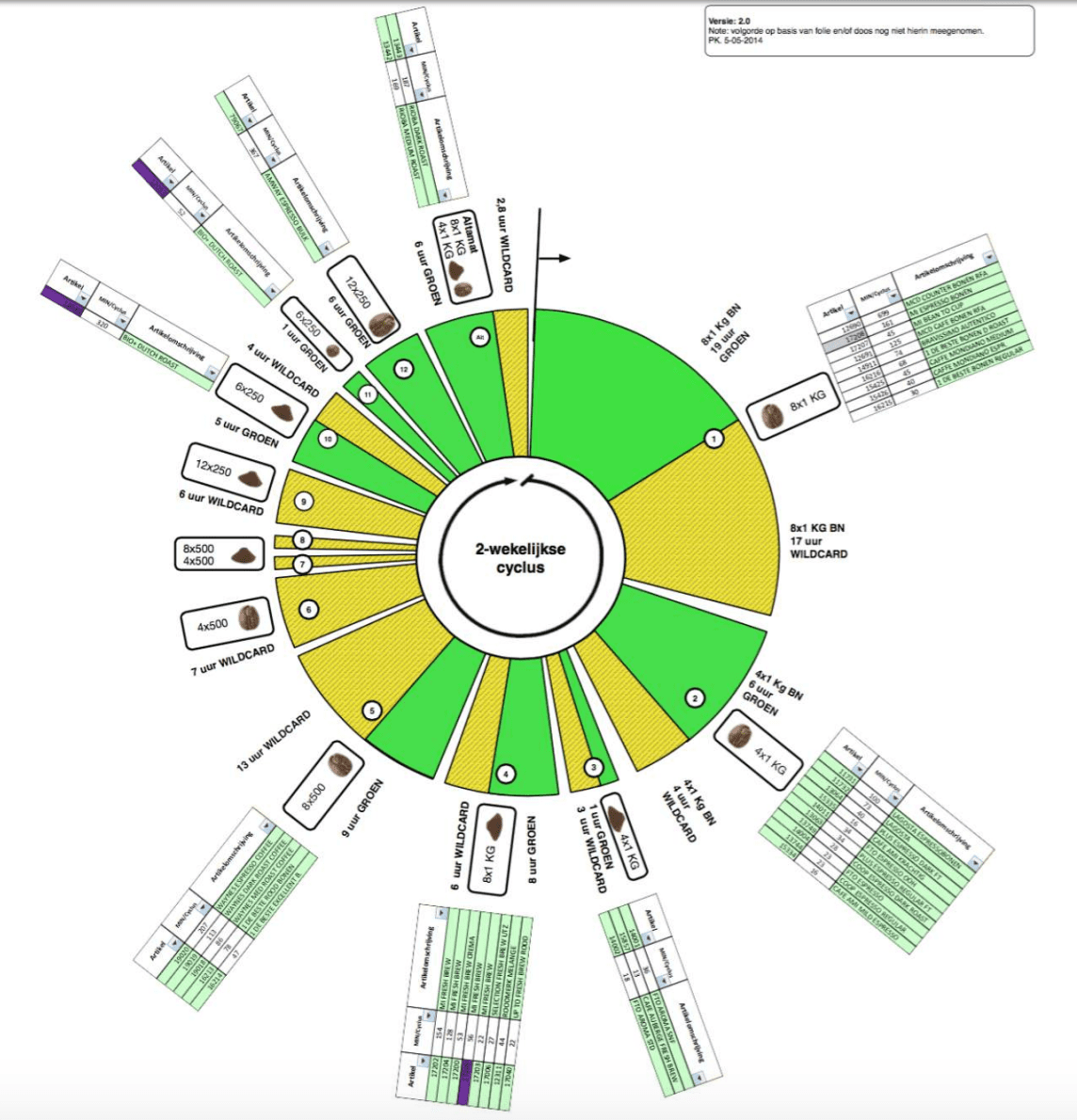

For each of the machines in use at UCC, we created a graph similar to the one pictured below. Looking at it from the inside out, we can see:

- Formats (weights and units per box)

- Product type (like blends)

- Film (printed, non printed, and what print)

- Box type (printed, not printed)

This graph gave us the current state of complexity, which we used to find the root causes and subsequently eliminate problems.

A big discussion between the production and lean teams and the Sales department followed, until the general manager finally said that UCC would be discontinuing every product selling less than €25,000 a year. He encouraged the sales team to reach out to the customers and to try to get them to buy a different product (in the process, salespeople found how beneficial talking to the customer is). Over time, we managed to bring the number of SKUs down to 775.

Understanding demand

To meet the second business prerequisite, we had to figure out two things:

- The composition of customer demand - the part of SKUs that represents the green stream (what UCC should make every day), the yellow stream, the blue stream and the red stream;

- The variation in customer demand caused by bullwhip effect.

A simple application of the Glenday Sieve helped us to understand what made up UCC’s demand, while to understand variation in demand and how it related to production we created a value stream map.

Production often struggles to mirror actual customer demand: the planning department faces variation on a daily basis and has to constantly readjust. Whether these changes in demand are real or created by the organization itself is a different matter, however. We often see a very flat demand at the customer side, but huge swings experienced on the shop floor. Taking the customer data to the extended value stream helped us see variation at each step and plan production accordingly.

Creating reliability

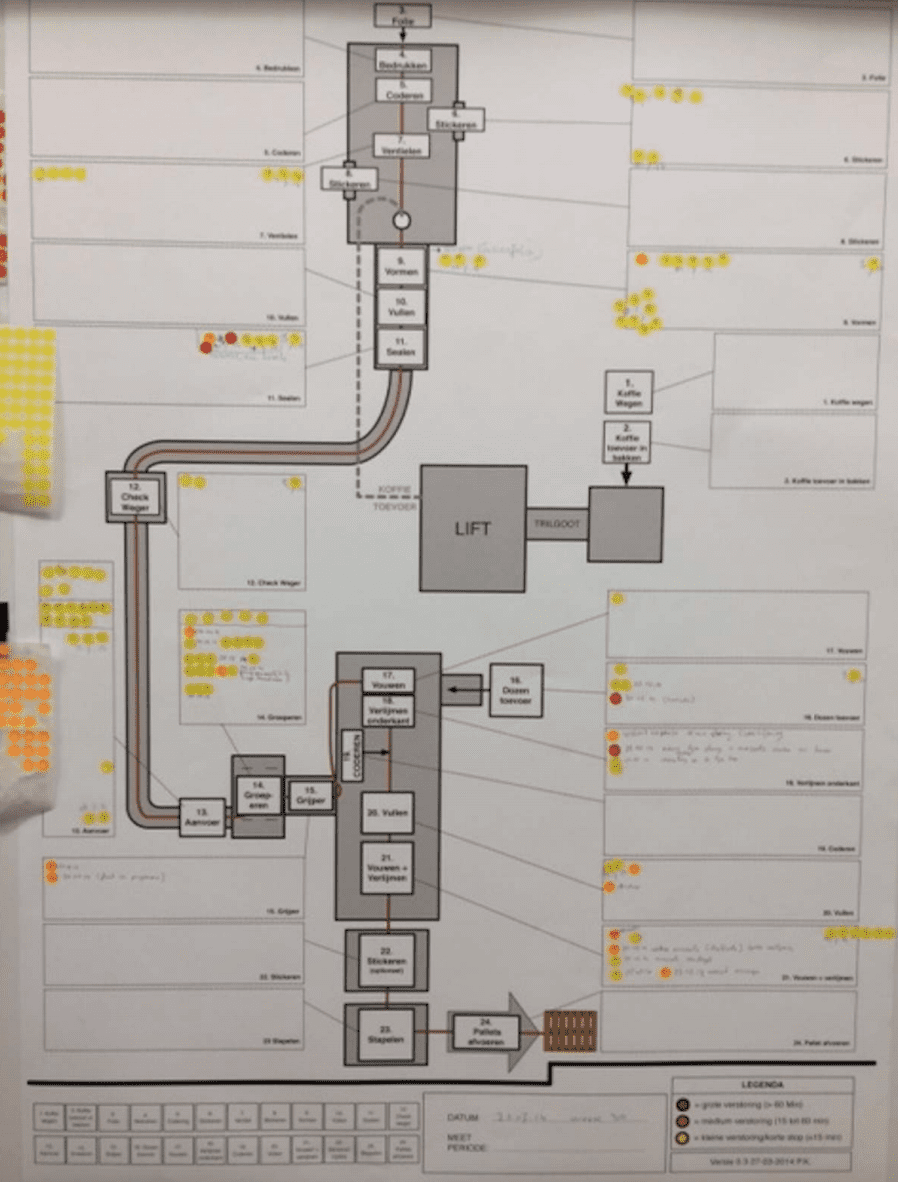

For this we needed a very structured approach. Downtime is often measured on a group of machines and, when asked, operators are often unaware of its real causes. Only a detailed analysis at each machine’s level would result in a significant increase in reliability.

To achieve a reduction in unplanned downtime we had to understand which particular part of a machine was responsible for it.

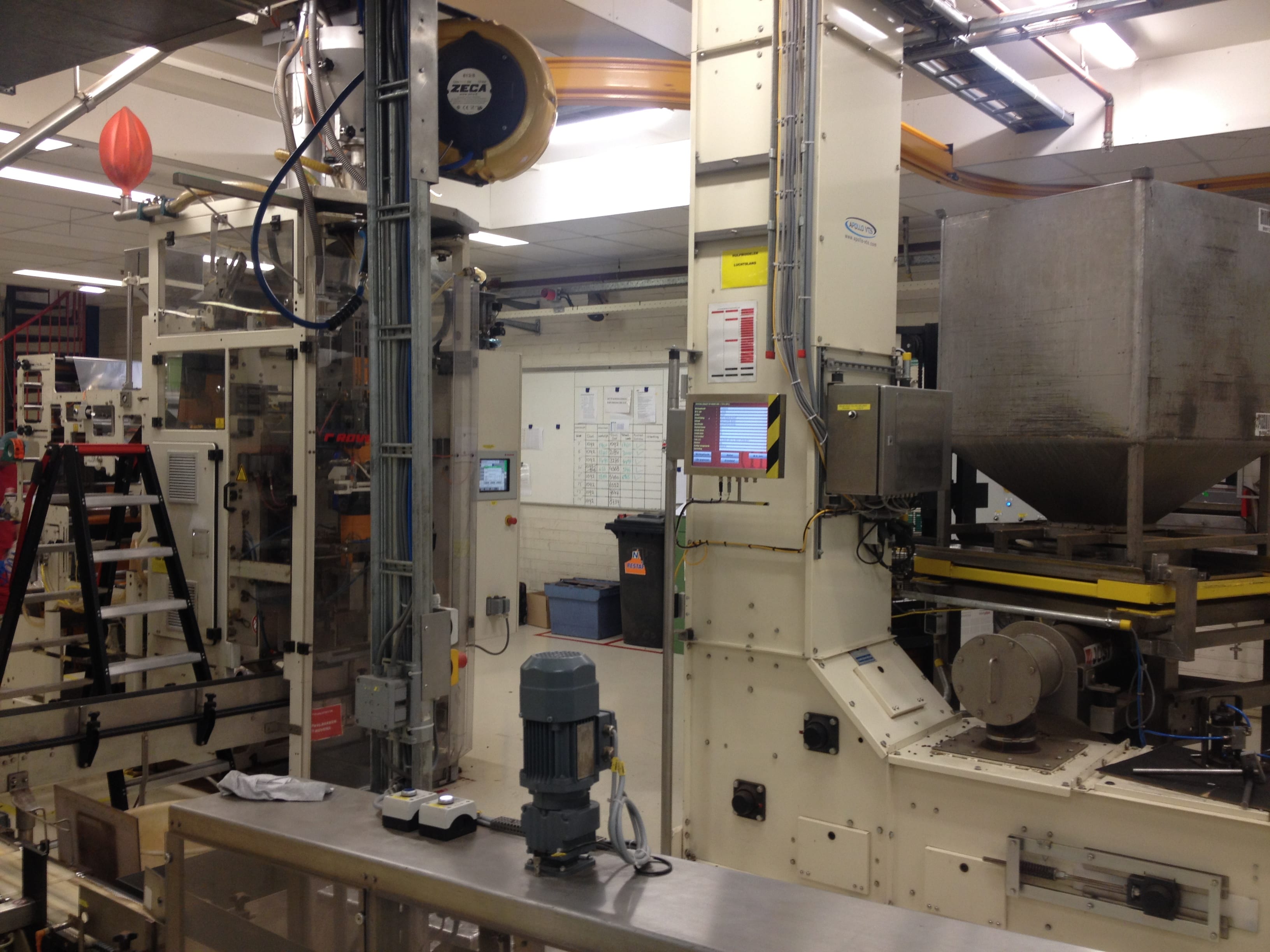

When we talk about a “machine” we often talk about a cluster of machines: at UCC, our “machine” was in fact made of a packaging machine, a filler or dosing machine, a scale, a labeller, a case packer, a glue applicator or a printer. It was an assembly process in which we had to find the causes of downtime, and it is interesting to see how it is often one part that is responsible for as much as 80% of a machine’s downtime.

We found that the best way to understand what part of a machine is responsible for the downtime is to visualize the layout of the machine in a drawing or printout. We then used little adhesive dots to visualize problems: yellow dots for breakages under 10 minutes; orange dots for breakages of up to 60 minutes; red dots for breakages lasting longer than 60 minutes.

With this system, we can calculate the contribution of each part to the loss of machine efficiency. At UCC, we found out that the glue applicator (hot melt nozzle), on a given machine, was responsible for a 7.5% loss of OEE.

Clearly, the maintenance plan had to be improved. We started daily standup meetings to discuss OEE results and try to understand, together, what the reasons might be for the problems encountered. Problem solving and root cause analysis revealed that the reason for the breakdown was small carbon particles in the nozzle, which in turn were caused by the hot melt units not being out in stand-by mode at night time and therefore overheated. As a countermeasure, we made sure that the units were indeed put in stand-by mode at night, which removed a critical cause for downtime once and for all.

As a result of our activities, UCC’s OEE increased from 55 to 62% for certain machines and from 73 to 85% for others.

RFS, WITH A TWIST

After working on the three basic prerequisites, we could finally focus on producing our green stream of products in a fixed pattern, as indicated by the Glenday Sieve.

But here’s where we encountered another hurdle. RFS is useful to understand customer demand and come up with the most efficient production sequence possible, but many organizations – including UCC – have too many SKUs and too few machines to apply the method as is. We had to adapt the use of RFS to our circumstances.

To do so, it was necessary to achieve a mindset shift and to get to the point where UCC was essentially planning its changeovers rather than its production. That is, planning based on time rather than volume. That’s why it’s important to have reasonably stable production before starting off with RFS.

Once we started looking at things that way, we were able to identify a fixed set of changeovers that production would do every day and keep in sequence. What makes this possible is the introduction of a changeover squad, whose only task is to carry out the changeovers, moving from machine to machine.

Another problem UCC faced was, of course, how to handle multiple products on a single machine and how to deal with the non-greens. With RFS, we want to eliminate the reds, incorporate the yellows and the blues into the greens, but there is always a certain (quite substantial) amount of products that can only be manufactured on a limited number of machines and that do not have the demand of the greens.

That’s when Lean Management Instituut came up with the concept of wild cards.

A wild card represents a slot in the planning structure where we can produce a blue or yellow product by performing the smallest and most logical changeover possible. It’s a way to remain in the green flow, while still being able to choose from a list of products that are similar to the green one we are producing.

In UCC’s case, the wild card was a coffee pack with a different print on it, everything else in the process being exactly the same. The changeover didn’t require much time and work. The wild cards system limits the number of big and time-consuming changeovers you need to perform on a production line.

Combine that with a supermarket-based pull system and you got yourself a very effective way to do RFS even with a limited number of machines for green SKUs.

Change has now come to UCC, and not just in the shape of better bottom-line results. We have been able to create an environment where people work together and strive to improve every day: every morning at 9.15 we kick off the day with a team meeting in our obeya. The whole operations team is present, including supervisors, logistics, planning & purchasing. Two years ago, we were using these meetings to understand the performance of four packaging lines; today the team has chosen to analyze it for 16 of them each day.

The team is motivated to understand the performance of the lines and really strives to get the most out of the equipment and their own work. It is important for us to carry out these activities as a team and actually share the responsibility for achieving our daily goals.

These days we are able to solve issues as soon as they pop up, and from the very start of each day our system is organized as an “improvement machine.” It’s our culture that has changed the most, and while we are still not fully satisfied with our results (can you ever be when you do lean?), we certainly are happy with the way we are making progress.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – By leveraging lean product and process development principles, Nichirin Spain is becoming more flexible managing last-minute changes in product design requested by customers.

FEATURE – The author discusses how the hoshin kanri process, coupled with effective coaching, helps us to tackle the challenges inherent to implementing change.

INTERVIEW – Drawing on 33 years of experience working in product development at Caterpillar, the interviewee reflects on lean in engineering.

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN – Small firms represent the backbone of the economy, and there is no doubt lean can help them improve and grow – by making the jobs they offer great. Without it, countries won't be great either.