Flexible by design

CASE STUDY – By leveraging lean product and process development principles, Nichirin Spain is becoming more flexible managing last-minute changes in product design requested by customers.

Words: Carles Rocafort Roca, Director of Product and Process Engineering, and Anna Villalta-Hernandez, Project and Laboratory Manager, Nichirin Spain

Tucked away from the rugged coastline of Costa Brava, a few minutes from the Catalan resort town of Palamós, lies our factory. You wouldn’t expect to find a manufacturing plant here: we are surrounded by fields and there are no other factories in the area. Perhaps it is the fact that we are rather isolated that has made us so resilient: our site, which supplies brake hoses to most OEMs, used to belong to Hutchinson and employ 850 people. Things have changed, however, and today there are 200 of us, employed by Japanese firm Nichirin.

We have been on a lean journey since 2005. Supported along the way by the Instituto Lean Management, we have been working with a lean production system and organizing ourselves in value streams for a long time. This is critical for us, as we find ourselves having to keep the work going with a quarter of the original workforce. Over time, however, we realized that improving manufacturing operations could only achieve so much without engaging the product development team.

Today, we are strong advocates of Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD) and its principles because we have understood that designing a product with manufacturing in mind is key to ensuring a timely, smooth and inexpensive introduction of that product into production. We aim to identify potential problems in the initial design stages, so that we can avoid them later on in the process – when they become more difficult and costlier to manage. With this in mind, we have built an obeya room where cross-functional teams can work on the different steps of a project, visualizing and discussing concepts like takt time, one-piece flow and work balancing in the cells as they pertain to engineering (ideas that have been present in our manufacturing operations for years).

Nichirin Spain co-designs products. What this means is that customers send us the specifications for a hose they need and we make suggestions on how to improve it or make its production less expensive or complicated. The work our clients do lends itself to several changes being made along the way: brake hoses are one of the last parts of a vehicle to be designed, which means that, once the main components (like the engine or the pumps) are in place, changes to the design of the hose are likely to be necessary to make it fit the available space. We need flexibility to effectively deal with last-minute changes requested by the customers, which is one of our biggest challenges (when there are too many, the risk is that our ability to deliver the work on time will be compromised).

Changes in the customer’s design also affect the equipment and the components we need to buy, and sometimes this happens very close to the product launch date. This can be a huge problem for us, because purchasing already represents around 75% of our costs. The obeya room is helping us to become more reactive to problems, by visualizing them and engaging our cross-functional teams.

HOW THE PROCESS UNFOLDS

Not everyone is familiar with our process, so let us take you through it.

Once we receive the specs from the customer (with the goals they have in terms of reliability, durability, and so on) from the Sales Manager, a team made of product engineering, process engineering and purchasing comes together to analyze the data. Together, we decide a quote to send the customer – along with our proposal on how to adapt the design of a hose in order to speed up production and lower costs.

After this initial stage is completed, it’s time for bidding – a process that can take several months. If we get the job, the Engineering Manager suggests a project leader and her team. Each department is asked to put someone forward for that project. We then nominate one person from every department for each project.

At this point, it’s down to the Design Validation Plan, which aims to ensure that our product (as designed) meets customer needs. For this, we typically use a prototype assembled in a car.

Once we have tested the prototype, we receive the Economical and Technical agreement (customers have to approve the drawing) and development can finally start. Before the design stage ends, a meeting must be held with the project team to go over the final design and the costs related to it.

In the development stage, we plan the machine and define the process using lean principles (balancing our processes to different takt times, establishing standards for each scenario that can unfold, and using value stream mapping to get an end-to-end view of the product inside our factory). This is when we normally do an in-house capacity study, prepare working sheets for production and process teams, and train staff. When we have the process clearly established, we do our internal runner rate and audit (sometimes the customer performs one too). Finally, we send the Part Submission Warrant to the customer – an important milestone for them.

We hold a meeting to discuss problems encountered during the validation process: this is where the bulk of the work moves to production and we start monitoring manufacturing. We do this by going to the site and checking all the problems that appear, machine after machine – from a capacity issue to a breakage. This is when we can really measure the success of our development process: the smaller the number of problems we see, the leaner our development work was.

LEAN IN PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

One of the things that really helps us is involving production in the project team from the very beginning to support process engineering. Representatives from the production team participate in the reviews and in all other meetings (which we are starting later than we normally would, because we already know customer requirements are going to change beyond recognition). The production department has certain standards that they share with the process engineering team: if we are considering a new cell, for example, we involve them to choose the layout. We only put together a new machine when production, process, quality and safety have agreed on the requirements.

Because of the nature of our work (modifying the settings of the machines we use takes months), we typically have to define the process before the customer gives us final approval. We are learning to be more flexible to allow for last-minute changes (we must assume that a big platform will have many more part numbers than we originally thought, and that there will be several changes in the product design). To avoid problems down the line – as much as we can anyway – we introduced an “interim process” that allows us to change different parts of a product rather than the whole thing at once. It’s a backup solution that enables us to get started with the changes before we have a final drawing in our hands and before we can run a FMDEA (Failure Modes, Diagnostic and Effects Analysis) to identify quality and safety risks inherent to the new design. The interim process also allows us to make a smaller investment in machines and to perform changes more quickly. It’s a temporary countermeasure, which we deploy while we work towards achieving a just-in-time response to changes that allows us to minimize our costs, as well as meet our safety, quality and service targets.

Thinking through alternatives together with the customer is critical, and it typically makes life easier for both Nichirin and its clients. We are trying to get our customers to see that communicating and collaborating with us from the very beginning is in their interest, because modifying a hose at the design stage is not the same as doing it when we are preparing the machines for production.

Working with customers is very important to us. Within Nichirin, each department has a different person at the client’s whom they deal with on a regular basis – for instance, project leaders don’t have cost responsibility, but they are best placed to communicate with the customer’s technical team. (In our case, the overall cost is a responsibility of the Engineering Manager.)

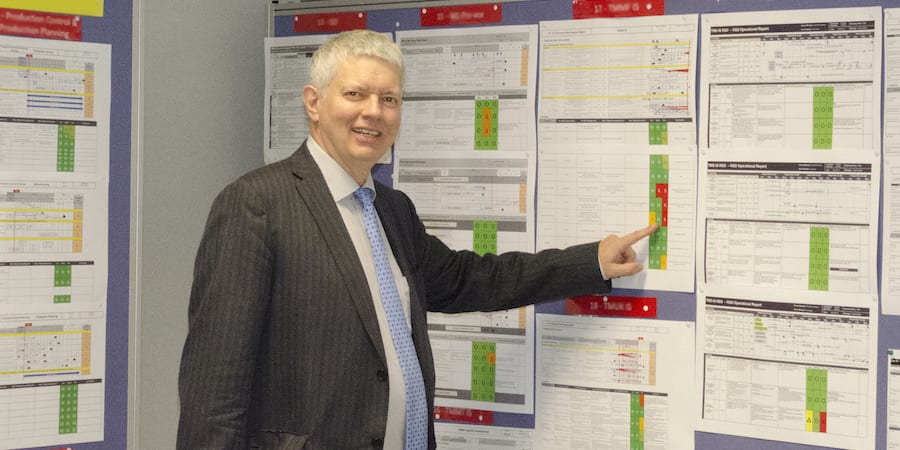

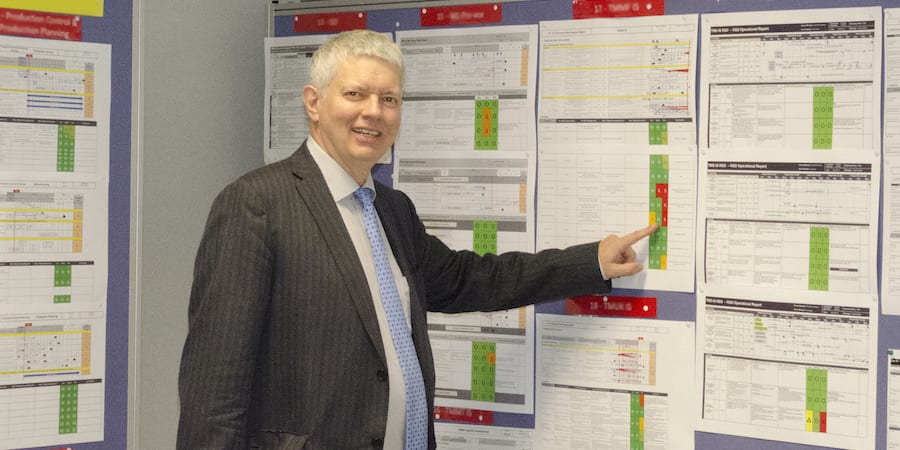

To assess progress on each of our projects, we use several visual boards hanging to the wall of our obeya room (we are de-digitalizing some of our data, in a bid to limit the amount of waste generated by poor communication). This is where we track KPIs and time, looking at things like economical agreement, frozen design, or whether or not we receive the machines on time. We are mapping important milestones that need to be met, because if we are late with one the whole project will suffer. We also display timelines for each project, which is a great way to get an overview of the situation (here, we rely on post-it notes of different colors to assess progress: yellow notes require attention, red ones are problems we need to escalate and fix).

We have periodic reviews (how frequent they are depends on the size of the project), in which we discuss problems that require urgent action. At the end of each key stage in the project, we run a mandatory meeting with every department involved in the project.

Lean product and process development principles and practices have proved key to the success of the introduction of new products. We are committed to continuing our work to further develop our LPPD capabilities, and we are excited to continue this journey of discovery.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

CASE STUDY – The author, who leads the CI team in a large real estate company, discusses the lean transformation of the business and role of the improvement team in it.

INTERVIEW - What happens in an organization after a move from silos to value streams? In this video, a Value Stream Manager from a Brazilian cancer treatment center shares her experience.

PROFILE – A commitment to learning and the humility to understand we never really know enough have led a Belgian mathematician to become a polyglot… and the CIO of Toyota Motor Europe.

INTERVIEW – Atlantis Foundries was able to achieve zero defects for three months in a row thanks to machine learning. Here’s why the human component can’t be discounted.