The lean playbook

FEATURE – The author reflects on how lean organizations are reacting to the Covid-19 crisis and discusses the tough questions they are asking themselves.

Words: Michael Ballé, lean author, executive coach and co-founder of Institut Lean France

A friend of mine was on a beach in Phuket, Thailand on that fateful December 26, 2004 when the tsunami hit. He told me that the water suddenly receded. The sand stretched as far as the eye could see and fish were twitching out on it. “If the sea’s gone,” he thought, “it’s going to come back.” He returned to his car, yelling at people gaping at the fish to get off the beach, then drove up the hill to see the catastrophe unfold only minutes later, from afar.

How you respond to a crisis makes a huge difference to the outcome. Crises don’t change people; they reveal who they are. And in general, there are three ways in which they can consider an activity: possible, impossible, or not impossible. In facing Covid-19, governments looked at face mask supplies (as well as tests, hospital beds, etc.) and some of them concluded they would never be able to supply them quickly enough and in large enough numbers. They therefore deemed this an impossible undertaking and went on to explain why masks wouldn’t help. As a result, it took them a long time to get serious about procuring such a vital piece of PPE. Others, on the other hand, realized that masks were essential for healthcare personnel – and everybody else – and started building up the supply chain as they went: it was not achievable right now, but also “not impossible”.

If you’re looking for a silver bullet, every solution falls short. If you understand that a response is built on an accumulation of small solutions, you start working right away with what you have. This is why first responder units are trained to move beyond the early sideration (this can’t be happening) to go through early steps, even though they don’t know what is going to happen. My friend didn’t know a tsunami was coming. In fact, he never expected anything of that magnitude. He just thought: “This can’t be good, let’s get out of here: I can get into my car and drive uphill.”

As the Covid-19 catastrophe unfold, we are now starting to see past the pandemic and make out the massive recession beyond the horizon. While we’re all confined, it feels like economic reality has vanished, but, like the sea on the day of the tsunami, it’s going to return. And I fear the return will be brutal.

Over the past few weeks, we have seen several examples of how lean companies have handled the crisis compared to many others. Many of these have been shared here on Planet Lean.

First, lean organizations took the contagion threat seriously early on, immediately working on keeping people safe through daily audits and the improvement of hygiene and sanitation practices. Secondly, they focused on protecting their customers who still needed supplying in a face of a completely new array of problems. Understanding the fragility of logistics, lean companies focused on keeping their processes working, even if at much lower volumes. Thirdly, they understood the anxiety and disorientation of their staff and set up coordination platforms, using available remote working tools to keep a steady thread of communication and, progressively, enable collective decision-making.

Fourthly, they started asking the bigger questions: what is going to change for good and what do we need to change right now? With no more knowledge than any other organization, but considering a variety of potential outcomes (in true set-based engineering style), lean companies organized think tanks on substitution of key materials and change of working practices, based on sharing local initiatives – and improving them on the go.

We’re not at the end of this, to paraphrase, nor at the beginning of the end. Maybe we are at the end of the beginning. Until there is a cure or a vaccine, Covid-19 is here to stay. It’s too early to say whether lean companies will really weather the storm better than the rest, but so far, it looks like it: they haven’t stopped operating and are working with relative serenity, with more collective decision-making and widespread people engagement. Although the recession’s tsunami wave is heading our way, they’re in better shape than the companies that have either completely halted operations or those that are already planning drastic cost-cutting across the board.

So, if they have access to the same information as anyone else, what makes lean companies different? The fact that, instead of just flying by the seat of their pants (and thus, unconsciously, reproducing one’s conditioning), they have a playbook to follow.

The lean playbook is unique in that it doesn’t give you answers. It asks a set of tough questions to spur thinking and adapt to changing circumstances:

- How do we keep staff safe (safety)? How do we protect customers (quality)?

- What is the challenge we need to face?

- How do we show greater respect for people?

- What do we need to go and see and understand firsthand?

- How do we better support local initiatives?

- How can we better coordinate teamwork?

This is of course the same playbook we use daily in lean companies under normal circumstances but, as it turns out, its impact is even more surprising when things go pear-shaped and all bets are off. No one knows how things will turn out, but this structured, yet open-ended game play helps us respond without locking ourselves into one or the other scenario – a good thing when, as we’ve seen in the past two months, anything can happen.

- How do we keep staff safe (safety)? How do we protect customers (quality)?

Masks or no masks? Tests or no tests? Full remote or partial? How can we continue to serve customers while keeping everyone at home? The situation differs radically as different countries, and even regions, react differently to the pandemic. The truth is no one fully understands yet how the virus spreads. What is clear is that you are in one of two situations:

- You have no cases of Covid-19 in the company and want to protect staff and customers from contagion;

- You have case of Covid-19 and need to quarantine to slow the spread of the infection until the virus runs its course.

To lean companies, this means working on two different processes at the same time:

- Improve hygiene and sanitation practices: 5S is a powerful tool to build on local practices and turn them into a more rigorous and practical way to maintain social distance (washing hands, physical distance, food control) as well as sanitation (cleaning and disinfecting) – with unexpected discoveries, such as the danger posed by shoes and so on. Experience now shows that over-stringent rules in Covid-free areas are overburden and largely ignored in practice. The 5S process, on the contrary, encourages a regular review of existing practices and adaptation to real-life use.

- Learn to work in lockdown: if an outbreak occurs in the town or, worse, in a site, the company needs to learn to work in full remote mode, even if it’s not ideal. Operations need the physical presence of the operators, but many processes can continue remotely so as not to stop the business completely.

General rules don’t help much. Dealing smartly with a crisis requires flexibility and creativity. People need to be responsible for their outcomes and not treated like wayward children. The lean playbook, with its game plays such as 5S or 4M analysis (Manpower, Machine, Materials and Methods), helps to develop local ways to protect customers and staff through rules build from the ground up.

- What is the challenge we need to face?

One of lean’s most basic promises is learning to learn: what, exactly, do we need to learn? What is the real challenge we need to face? This means setting aside those to which we have on-the-shelf solutions (which we already know how to solve) and looking squarely at the ones where we don’t. What are the new problems that we don’t have answers to?

The shortlist of top challenges that have appeared in these first weeks of the epidemic are:

- How do we help sick employees?

- How do we supply protective equipment?

- How do we work remotely?

- How do we keep basic operations running safely?

- How do we find substitution solutions for closed-down providers?

Answering these questions with “we don’t know how to do that!” or “that’s not our department” prevents us from thinking creatively about how we respond, get things done, and then learn from our responses to further improve and learn to master the new circumstances.

Forcing ourselves to face challenges shifts us from thinking it’s impossible to it’s not impossible, and that makes a world of difference.

- How do we show greater respect for people?

In times of crises, everyone has an opinion and these opinions will differ greatly. Showing respect means making the greatest effort to understand other people’s point of view (understanding doesn’t mean agreeing). In the early days of the crisis, opinions ranged from Covid-19 being “a big flu” to it being “a new plague”. Listening to the wide range of positions was a key driver in having lean companies move fast – enough people were genuinely terrified that the threat had to be taken seriously, whether you agreed with their assessment or not.

The deeper the disarray, the more people need to feel engaged with the solution and listened to. Their opinions have to be taken into account. Showing greater respect for people has often meant using new remote tools, such as Zoom, to open strategic and leadership discussions to a wider circle of people and making sure that all voices were heard.

- What do we need to go and see and understand firsthand?

A lockdown makes it impossible to “go and see” and, indeed, most gemba walk visits have been canceled – but the principle still applies. Looking at the real thing, in the real place with the real people showing you remains the only way to grasp what is truly important – as opposed to what is reported. Particularly in times of high uncertainty, we can wonder about what we really can figure out firsthand:

- Who is the source of this piece of information?

- Is this something they’ve experienced for themselves or heard from someone else?

- Is there a way to check this?

Of course, as a manager, there are still plenty of opportunities for going to the gemba, even in a lockdown. Certainly, many operations will be running slow or even stopped, but it’s still amazing what you can pick up by just looking (our sight triggers different parts of the brain that reading or listening can’t).

The obvious thing that comes out of go and see is, as previously mentioned, the very wide range of circumstances and conditions. Understanding in one’s bones that one-size-fits-all solutions are not going to cut it is the starting point of smart, flexible responses.

- How do we better support local initiatives?

Precisely because people are in very different sets of conditions, their initiatives are going to be very interesting. This isn’t to say that all initiatives are good – some clearly are, some clearly are not, and most probably won’t make much of a difference. But each of them is a very concrete starting point. People are smart and although they don’t always consider all the ins and outs, they do have a reason for suggesting what they suggest.

A large part of supporting their initiatives, beyond giving them the permission to try, is creating platforms to share these ideas and encouraging others not to simply apply, but to copy and improve. If we can inspire one another and make ideas work through painstaking trial-and-error, we will come out of this, collectively, much stronger.

“Go ahead and try” is a key part of the lean playbook and an essential one in times when everyone feels shipwrecked and castaway on the beach. The worse the shipwreck, the more we need to dig wells to find fresh water, look for edible fruit, trade with the locals and build smoke signals to be spotted from afar. Everyone needs to pitch in with their ideas, and we need to replace our natural “it won’t work” reaction with “make it work.”

- How can we better coordinate teamwork?

The study of how Toyota has handled previous crises starkly reveals the importance of coordination rather than control. In an emergency, the lean playbook starts with facing up to the challenge, breaking it up in manageable chunks and then coordinating sub-groups of voluntary people so they come up with local initiatives to solve problems safely.

Coordination calls for the creation of obeya-like war rooms, spaces where everybody can see at a glance what various groups are working on and who needs help. This is very different from top-down newsletters or bulletins where management tells the front line what is going on. On the contrary, here the management team organizes an open space for people to see for themselves where to get involved – and commit to keeping it updated in as close as real-time as possible.

With the current crisis, lean companies have used remote tools to recreate such spaces in a virtual form, taking a page from the book of companies working already in full remote mode before the crisis. In such a scenario, coordination and information sharing clearly become essential, which means that trying to reproduce remotely traditional ways of working won’t work (that’s why we should strive to use virtual obeyas rather than newsletters, for instance).

What early take-aways can we garner from the steep learning curves of using the lean playbook during the Covid-19 pandemic? Even though it’s way too early to make definitive statements, we can clearly see that, first of all, having a clear playbook made a huge difference in the first days of sideration. Rather than stay frozen like deer in the headlights, lean companies moved fast and early and avoided paralysis or total shutdown. As time passes, the gap with those that did stop keeps growing very visibly, which is likely to affect future outcomes considerably.

The second, unexpected, take-away is that reflexes of command-and-control are stronger that we’d have thought, even in experienced lean companies. Efforts to build coordination platforms and collective involvement in experiments have been harder than expected, hitting repeatedly the rigidity of chains of command and the inability of staff structures to decide quickly on anything. If we want to change fast and adopt remote work effectively, as well as the flexibility to switch from and to remote according to the development of outbreaks, we must re-learn the coordination skills managers had before management-by-objectives became the dominant approach in the West.

Finally, the lean playbook is so effective exactly because it is open ended: these core questions can be asked again and again as the situation evolves. They are a starting point, not the end, and – as in any scientific enquiry – allow us to begin with a quick, possibly wrong diagnostic and make it evolve fast as we try new things and discover new facts. They enable us to engage a wide network of people in contributing creatively and building on each other’s ideas to make the new processes work – something that doesn’t simply happen every time new rules are introduced, arbitrarily, by the top.

Not only does having a clear playbook help in any crisis, having an open-ended playbook based on a diagnosis and a bias for action creates a basis for learning: early responses are reflected upon, by asking the same questions again and again, and answers evolve. This, along with keeping everyone involved supports fast and serene change – the essential qualities we need to overcome any crisis.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

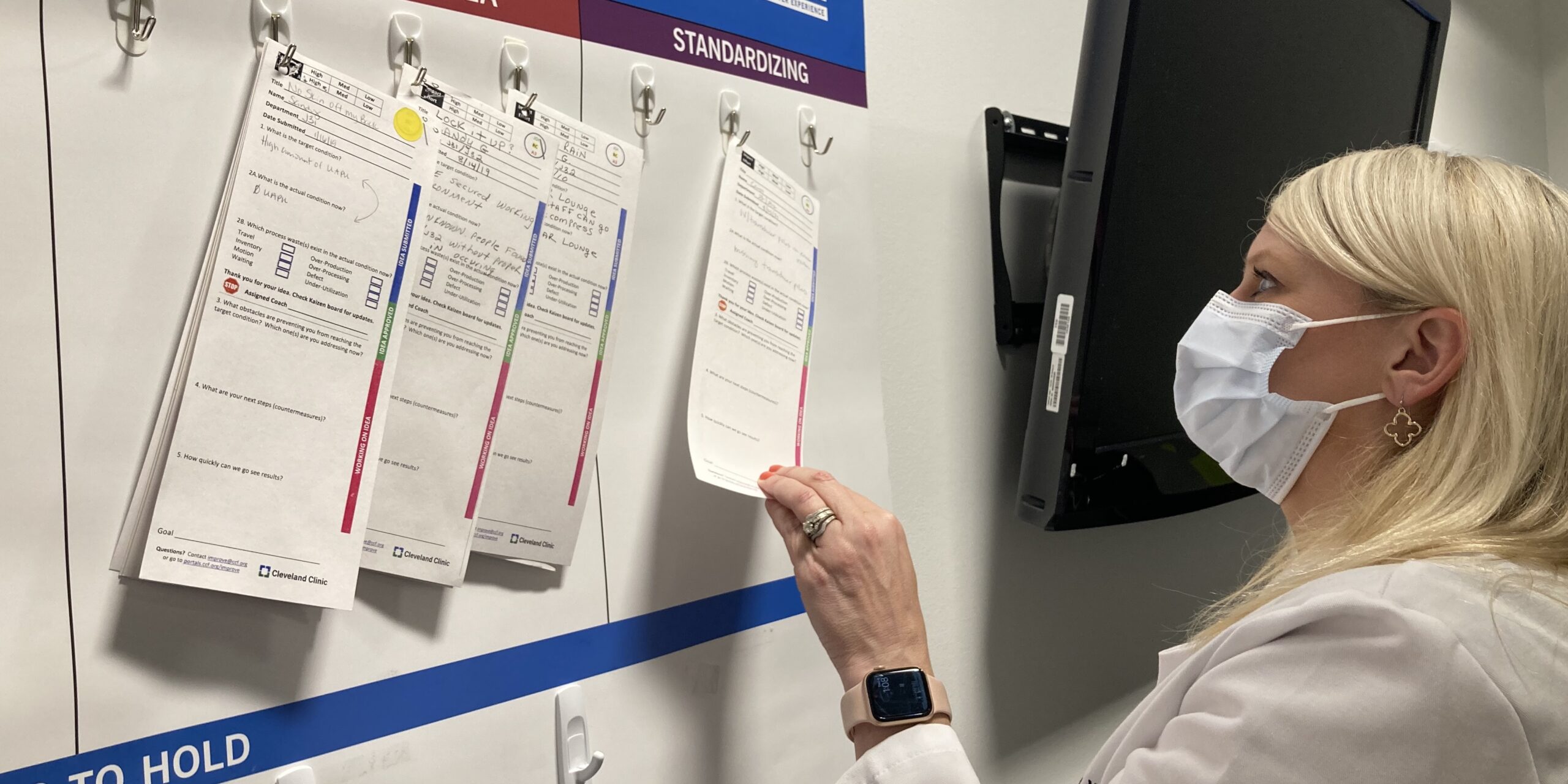

INTERVIEW – Cleveland Clinic has been on a lean journey for a few years now. In this interview, their Chief Improvement Officer and Chief Nursing Officer talk continuous improvement, metrics, and sustaining results.

FEATURE – We often think that making every product customers might want – no matter how little they sell or how much complexity they add to our schedule – is inherently lean. As Toyota understands quite well, however, it is quite the opposite.

CASE STUDY – Over the past four years, by developing its kaizen capabilities and crafting a better approach to maintenance, a Turkish gold mine has significantly reduced its extraction costs.

FEATURE – Using data from a recent piece of research on logistics, the author discusses how Lean Thinking contributes to a more efficient and effective way of dealing with problems.