Software vs visual management

FEATURE – We often spend a great deal of time and effort trying to fit our organizations into a box instead of building a box that fits our organization, says Sharon Visser.

Words: Sharon Visser

In the age of technology, countless software options are available to us to manage the financial and operational side of our businesses. These products are generic, off-the-shelf, but we pretend to use them as if they were our own.

At a time when providing unique services and products is key to survival, are we truly aware of how much our software dictates our response to the customer? How often do software limitations force waste onto our organizations?

Every time we do a workaround to accommodate software, we create waste. And of course, the more workarounds we must do, the easier it is to open the door to errors that impact the customer.

I am not saying go out and dump your software, of course, but I do think it’s important to recognize where software can create more work than a simple manual system and how these inflection points impact the customer.

By now you’re probably wondering what any of this has to do with lean visuals. Well, I believe that good lean visuals developed in house by the people close to the work provide the best starting position for the development of a flexible, bespoke reporting system that will provide value to the customer that software is not yet able to provide.

It is how we respond to the problems to be solved where the work is being done that influences the financial outcome that we see in the Board room. In my opinion, ensuring that gemba visuals function well and that leadership attends huddles around these visuals with the people doing the work creates an incomparable and dynamic synergy within the workspace and leads to the financial outcomes we wish to see.

Let me give you a simple example. In 2020, I was assisting a transport company that operates in the Okavango Delta, providing a service to a tourism industry that had come to a complete standstill during the Covid lockdowns.

Upon re-opening, the owner called me from New Zealand and asked me if I could help her to get the business up and running again as she was now trapped on the other side of the planet.

When I arrived at the business, management and staff had no idea where the company was going to get the revenue to survive. Fear for the future had taken a grip on everyone: people were not just worried about getting Covid, but also about losing their jobs.

After my initial observations, I asked the financial manager to give me an idea of how many trucks they would need to load each week to cover expenses (which had become our first target). We agreed on the lucky number of 13 truck loads a week to cover the basic financial needs and keep everyone employed.

This is where Kamishibai came to the rescue. We could have used a ladder chart, but we needed the physical interaction and the opportunity to monitor marketing efforts. I also wanted to measure the number breakdowns, as I realized that the technicians (who had been in lockdown themselves for four months) would have probably lost their routines. I feared this loss of work habit, coupled with the pandemic trauma factor, would impact the quality of their focus and workmanship.

On the Kamishibai board, we had five rows with 14 hooks. For each hook, we created a red and green tag. The first hook stated the week number.

Every day at 8 AM we met by the board and turned over the trips that had been made. We now had a simple goal for one week at a time: if there was a breakdown, a yellow warning sign would be placed over the card representing the truck and follow-up was done to establish the reason for the breakdown. In the first week, we had three breakdowns. The follow-up activity made the technicians aware of the problem and the costs of a lack of quality.

Please note that when we developed this board, I explained why we were measuring and that I was expecting technicians to struggle as they had lost the work habit. This encouraged them to re-establish their service routines as quickly as possible. They all understood and the number of breakdowns resulting from workmanship issues went down. I did not have to discipline them about this; I just explain what happened and they fixed the problem themselves. They were all aware of the seriousness of the current situation.

We then had a marketing meeting, where we used a sales funnel visual to see how we could improve revenue now that the tourism industry had come to a virtual standstill.

Some of the trucks had cranes on and others had a fuel tanker adaptation to load and carry shipping containers. The company also had forklifts available for offloading heavy items. The adaptive and versatile nature of this fleet provided an opportunity to deliver value to organizations outside of the tourism industry.

The organization started to market its transport services to building contractors and mines in the area and managed to pick up some additional work. Flipping over the tag from red to green was comforting for everyone: it quelled fears and gave a simple goal to work towards, which was about as much as everyone could emotionally cope with over this period.

Taking into consideration that here in Botswana there was and is no social security or furlough schemes to fall back on, the only option they had if we failed was unpaid leave – a scary thought when one has a family to look after. This kind of trauma is paralyzing, and it makes it hard to find creative countermeasures.

When the board started to function, I made some smaller tags that could be slipped over the card that had been flipped. We could now record if it was a tanker, a crane, a container, a forklift or an ordinary load. This gave motivation to the marketing team as they could now see the results of their efforts.

At the daily huddle around the board, we were able to discuss problems and find countermeasures. All of this contributed to the survival of the business over this difficult time.

We were given an opportunity to talk about the work by being able to see if we were ahead or behind. The visual board allowed us to bounce ideas off each other, thus encouraging innovation and communication.

Before the visualAfter the visualHad no target to work towards.Had a weekly target to work towards.The number of breakdowns was not clear to people.Everyone could see the number of breakdowns.Senior management found countermeasures for problems.Team stood at the board together and found countermeasures for problems.Marketing team had no idea if their marketing efforts were working.Marketing team could see daily the results of their efforts.Did not know if they were ahead or behind.Knew if they were ahead or behind.

I am not saying that software does not have a place in our world. In fact, even this company had a very sophisticated fleet management system. Yet, not everyone had access to it – nor the skills to use it. Conversely, everyone can flip a card from red to green or add a tag that gives vital information about the work being done. Front-line people had an opportunity to problem solve with the management team, which fostered mutual respect and engagement. And remember: without respect and engagement, providing value to customer is so much harder!

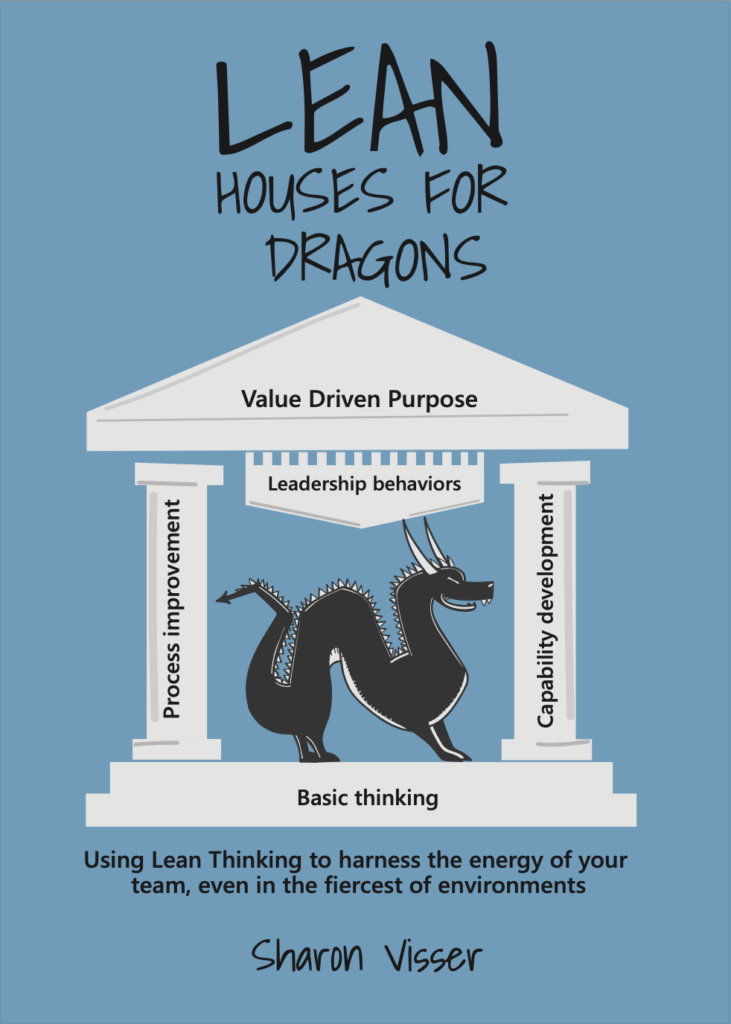

Sharon's unique book - Lean Houses for Dragons - is out now. Buy it here.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – The Consorci Sanitari del Garraf, a Catalan hospital PL has come to know well over the past few years, just won an Honorable Mention award at the World Hospital Congress.

INTERVIEW – Last month we caught up with Toyota veteran Art Smalley in Las Vegas and discussed with him the role of leadership in a lean transformation and the four different types of problem solving he talks about in his new book.

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – Ahead of the holidays, for his last column of the year, the author reminds us of the power of sharing. Go out and spread the lean word!

ARTICLE - How can creativity and standards coexist? How do we move beyond silos? How do we fully understand the voice of the customer? Dan Jones reflects on three key questions for the lean movement.