The fantastic lean transformation of an Italian hospital

CASE STUDY – There is more to Siena than the Palio: the Tuscan city boasts of one of the most advanced examples of lean healthcare in Italy. We asked the team at the University Hospital how they are doing it.

Words: Caterina Bianciardi, Lean Manager, and Giacomo Centini, Chief Financial Officer, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese - Siena, Italy

For our hospital, the first push towards lean thinking came a few years ago from a project promoted by the regional government, which aimed to optimize patient flow in Tuscany’s hospitals.

It was a very comprehensive project, through which we started our work in the Emergency Department. It was the area of the hospital (it treats 55,000 people every year) where we knew we could get great results in a short time, even just for the fast nature of the work there – we are used to measure it in minutes or hours, rather than days or weeks. We saw the ER as the best way to put ourselves to the test and show the power of lean to the rest of the organization.

As it often happens in Italy, we began by presenting the project to the trade unions and then to the entire staff of the Emergency Department: doctors, nurses, and healthcare assistants (we call them operatori socio-sanitari – or OSS). From there we started a month-long observation: we identified “patient 0” and built a value stream map around her. We then organized a number of meetings, first by profession and later on all together, to determine potential ideas for improvement.

The result was a list that, two months later, we presented to the board and the unions. Once we got the green light, the real implementation started.

The observation of our processes had already taught us much more about how the hospital works than we ever knew before, and gave us a better understanding of how to implement lean in a healthcare setting.

One big lesson we learned then was that you don’t necessarily need all the sophisticated tools: a simple mapping of the process and a few kaizens can be enough to get started.

IT’S ALL ABOUT EDUCATION

At first our approach to the lean transformation was a bit more top down, as it often happens: without education, we quickly realized, people won’t know what you are talking about.

Organizing training sessions was the fastest and most effective way to touch people at all levels, and to get them interested. To date, we have reached 2,000 professionals working at the hospital, which we consider a great success. We know it’s working because while at the beginning we “pushed” training out – deciding the topics it covered and hoping to get as many people as possible to attend – now people come to us, asking to provide training on the things they are interested in delving into. The standard introductory courses are fewer and fewer these days, and we are making an effort to customize our training offering based on the needs of our staff. It’s on-demand training, if you will.

Once people are equipped with a basic lean knowledge, they get curious and want to try it themselves – and there is no doubt that the success of the ER experiment also helped us to ensure buy-in.

Our transformation is built on projects, with a clear desire of our CEO right from the outset to leverage lean to get contributions from people. He wanted to get to a point where we couldn’t count the number of projects we are working on at any one time, and we are there now. It’s a great feeling.

We started with small projects here and there, and found them to be a great way to get people to ask questions. Currently some projects stem from the need to meet a requirement set by the board (which is linked a number of budgetary initiatives), but a lot of the time they are the result of our people wanting to improve things. Needless to say, those they suggest themselves – bottom-up – are the ones that tend to work best.

It’s not a walk in park – don’t get us wrong. We had successful project as well as many failures. Whenever we failed, our response was not to point fingers, but to give people even more responsibility. At times we have slightly altered the focus of a project to make it easier for people to get on board – it’s all too easy, in the excitement of making improvements, to think too big and make the task daunting.

We like to go with the flow, in reality, adjusting the course as we go. Whenever results come in (and they do all the time), we use them to get people even more exciting. It’s a snowball effect. It’s as if lean is constantly reinforcing itself now that we have passed the initial hurdles.

THE IMPROVEMENTS

Speaking of results, ours have been quite remarkable. The one we always tell people about is the one that resulted from our experiments in the Stroke Unit. We assigned a working group – made up of people from different units – to this project, which aimed to shorten the time between admission and treatment of patients suffering from a stroke. We mapped the care path using VSM, we analyzed the data and we spent a lot of time at the gemba. This allowed us to identify the bottlenecks and problematic steps in the process, and to come up with appropriate countermeasures: the time between admission and treatment went from 76 to 48 minutes. Sure, the result in itself was great, but the best part in our mind is the fact that the improvement was entirely led by people and its impact on patient outcomes is immediately clear. That’s the sort of project you’d always like to have!

Another project we are really proud of is aimed to shorten the set-up time of surgical theaters. To achieve this result we used SMED, cutting set-up time by 20 minutes. The interesting thing about that improvement is that it was an entirely new approach for us, but it somehow got the nurses really interested – so much that since then the use of lean in Surgery has grown organically, with 5S now applied in all our ORs. The warehouse is next, the nurses are telling us.

While these are perhaps two of the most successful projects we had (there is also the 50% reduction of infections in the Intensive Care Unit), there are too many and it is getting hard to remember them all. Definitely a nice problem to have!

As a side effect, lean also had a great impact on our financial results, which the board encouraged us to calculate as they thought that piece of information might make it easier to prove the value of our efforts – whether we like it or not, money is still important. Between 2014 and 2015, lean improvements saved the hospital around €3.7 million.

What we want to do is improve patient outcomes and make this hospital a better place to work for our people. If, in the process, we also manage to reduce our operating costs… well, that’s a win-win.

A (LEAN) DAY OF CELEBRATION

There is always a lot of discussion in the lean world about rewards and recognition. At AOU we think we have found a great way to let our people know how much we value their contribution to the overall transformation of the hospital. People love it and we don’t see a better way to recognize their achievements than letting them present them in front of 300-strong audience.

Every year we organize a Lean Day as a way to celebrate the efforts of those who completed a lean project, while offering our staff something of a fun day out.

The event is open to anybody, and we of course try to get people who still don’t know lean to come so that we can try and inspire them to follow the example set by their colleagues. You can read books and attend a course, but nothing shows you the power of lean more than listening to your peers talk about its impact.

In the Italian healthcare system (which is considered one of the best in the world, even though it is still marred by waste) there are very few examples of lean. The Lean Day is a way for us to open our doors to the rest of the world, hoping to help lean spread in our sector. This is bigger than us, and it is important that everybody becomes aware of how transformational lean thinking in healthcare can be.

We also hope that the Masters degree in Lean Healthcare, which we run together with Siena’s University, will contribute to developing the next generation of Italian lean practitioners in the healthcare sector.

CHANGES, FROM THE WARD TO THE BOARD

As engineers talking to healthcare people, we have certainly discovered how difficult and lengthy a process it is to build trust and to make people understand we are not the enemy. The number one question in their minds is, “What does an engineer know about healthcare?” Indeed, we had to learn a lot about how a hospital is run, but once we got there new channels of communication opened up and things got smoother.

Another challenge is, of course, getting everyone in the board to understand the value of what we are doing. We are very lucky that we are given a lot of freedom in what we do, and that our CEO was one of the leaders how championed the regional project to optimize patient flow that we mentioned earlier in this article.

Difficulties may still appear up and down the organization, but so are changes. In the past year or so, for example, we have started to have regular meetings with the board to update them on our projects and results. Until fairly recently it was nearly impossible to get a meeting with the medical director… in fact, many people didn’t even know who the medical director is!

Because lean is ultimately driven by people, it is great to see the biggest change having taken place in the operational branch of our organization. These days people have a completely different way of solving problems: there is more structure to their work and their improvements. It is getting more and more common to join a meeting and to find data already available or a process already mapped. There are clearly management elements that have made their way into the operational level of the hospital.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

COLUMN – Creating a learning environment that welcomes problems and experimentation and adapts to market changes should be our main objective. So why do we stick to obsolete ways to teach and develop people?

VIDEO - The director of a hotel in the Canary Islands explains the hoshin efforts taking place in the organization and takes us through the lean strategy deployment boards she uses to track progress and highlight problems.

FEATURE – Using the Japanese tradition of daruma dolls as an example, the author explains how to turn continuous improvement into concrete challenges – and, from that, real competitive advantage.

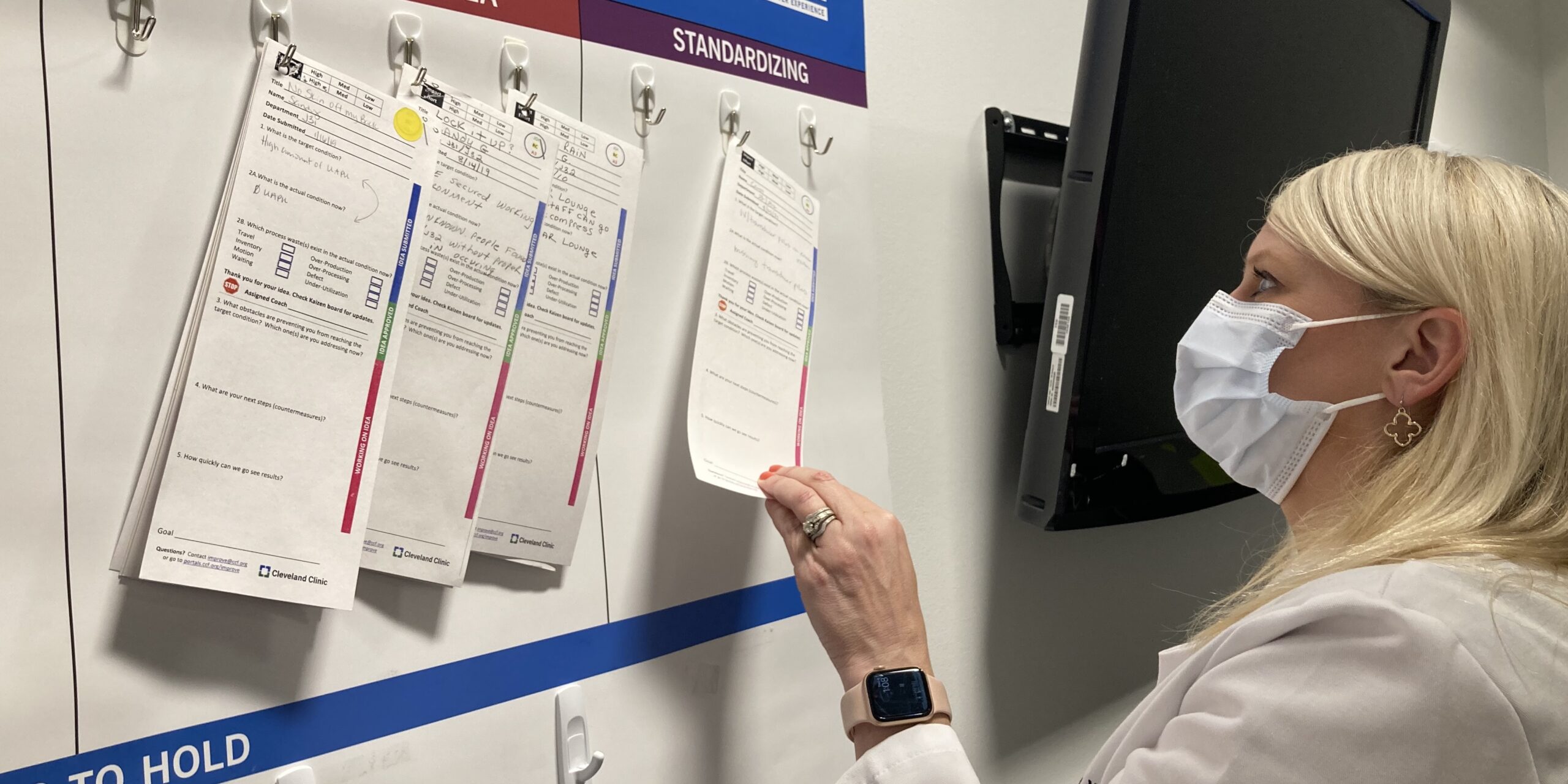

INTERVIEW – Cleveland Clinic has been on a lean journey for a few years now. In this interview, their Chief Improvement Officer and Chief Nursing Officer talk continuous improvement, metrics, and sustaining results.