Questioning the lean vocabulary

INTERVIEW — In this Q&A, Michael presents his latest book—a glossary of lean terms that’s meant to challenge our long held beliefs about lean concepts, and to make it fun.

Interviewee: Michael Ballé

Roberto Priolo: You have written all kinds of things on Lean. Why did you feel the need to write a glossary at this point in your career?

Michael Ballé: Honestly? It came together by complete serendipity. I was playing around with ChatGPT illustrations for some of my LinkedIn posts and my son said, “Don’t do that, it’s awful. Why don’t you make the cartoons yourself?” So, I started drawing a few cartoons—literally on the back of envelopes—and posting them. It was fun, so I continued and progressively realized there were many core lean concepts that were no longer discussed, and even some key terms like chorobiki or mendomi that had completely disappeared from the conversation. I believe that without these keystone concepts, Lean gets interpreted (or translated, I should say) in very weird ways that miss the spirit of TPS. I then asked myself: what would these key concepts be? That’s how this glossary came to be. It was never meant to be a lexicon of lean terms (we already have that); rather, icebreakers and reflection starters for the students of Lean.

RP: How did your early research on mental models and your sociological training influence the way you approached defining these terms?

MB: Interesting question. Thirty years ago, when I started my PhD dissertation, I realized you could evaluate people’s “degree of thinking” by the way they reasoned out loud: level one, they think in stereotypes (“just-in-time is production without stock”); level two, they think in general rules (“increase the frequency of deliveries to reduce the stock level”); level three is conditional rules (“understand what kind of variation your stock protects against, and increase frequency of deliveries, or reduce batch sizes, or clarify flow, etc.); and, finally, level four is ad hoc thinking, the kind of thinking we see the sensei do—what is specifically happening in this specific situation. Day to day, people will easily reduce complex problems to the part they understand and mostly gravitate towards stereotypes. My purpose was not to define terms as such (others have done that much better than me), but to discuss them so readers can start thinking in higher levels of reasoning, in their context, and draw new insights.

RP: What does it mean to “question the vocabulary,” and how can we make this a regular part of our learning practice?

MB: What is the meaning of these terms? In Toyota’s context? In our context? Visiting Toyota plants around the world made me realize that many of Toyota’s core lean concepts were interpreted differently in different cultures, even within Toyota. And then, outside Toyota, people would pick up a concept seeing a solution to their problem, without understanding the problem Toyota was trying to solve with this idea. For instance, many in the West get hung up on “standardized work”—they see it as a way to solve their taylorist problem further, with maybe more empathy—but the prevailing Western obsession is to make the operators follow the prescribed way in painstaking detail. You can see this outlook in some Western Toyota plants as well. In Japan, standardized work is clearly about following takt time. In order to deliver good parts exactly on time, each operator has to self-study how they work in order to keep their cycle time reliably at takt. Team leaders, supervisors, and standardized work sheets are there to help them in this study of how they work, not just to make sure they “follow the standards.” In the West, I frequently see cells with great emphasis on standardized work without pull (check out “chorobiki” in the Glossary) or compassion (“mendomi,” making sure the operator is in good physical condition to achieve the standardized work) and without focusing on kaizen to improve the standardized work (we’ll do that when all is standardized). This is what questioning the vocabulary means: what does this term mean? How do we see this idea as a solution to our problems? What problem did Toyota solve with it? Do we really understand the purpose of this concept?

RP: What is the lean term that surprised you most in how differently it is understood (or misunderstood) outside Toyota?

MB: Flow. Definitely flow. You keep hearing, “we must improve the flow in a process and then we’ll see.” Pull is seen as something we do when we grow up. Every cell I’ve seen at Toyota suppliers started its lean journey by being included in Toyota’s logistic system and… “pulled.” This dynamic, of course, creates (or surfaces) many problems, which then need to be solved one by one; as they do that, people learn to better understand their client, their machines, and their work. Back in the 1990s, I started my study of Toyota having already worked on business process reengineering and published a book about it, so at first I thought I got it: improve the flow, and good things will happen. But I also realized that most reengineering attempts I had been part of had failed. When I saw how Toyota sensei went about it, it hit me: the process is what it is, and opportunities of truly improving flow, such as reducing parallel processes or reducing batches, are few and usually difficult to pursue. This obsession with flow hides a critical part of the process: the information flow that drives it (how it’s scheduled, how it is presented). For instance, a cell receives a work order—it needs to produce so many parts by this date—and it’s then up to it to organize itself to do so. Receiving a kanban from production planning is very different: make X number of parts now and place them in a shop stock where internal customers are constantly pulling from. The nature of the information is very different and so are the problems it poses for the cell—and so will be the solutions. This whole idea of “lean = flow”, while not wrong in absolutes, hides the information control dimension of what Toyota discovered, and the consequent planning functions (product planning to pull new products, engineering planning to make sure new machines arrive on time in the plants, production planning to make sure the information flows correctly on the shop floor, etc). Sure, flow if you can and pull if you must; but, in reality, start with pull and it will teach you how to flow. Most process fixes just make things worse by increasing inflexibility rather than making operations better at handling variety.

RP: Did you follow a specific process to write the discussion of each term? And what’s the role of the cartoons accompanying each definition?

MB: No process. Just thinking about what arguments we have been using to discuss each term in the previous century that we struggled to understand then. The cartoons were an integral part of writing the definitions: I wanted to capture the run-of-the-mill facepalm, hair-raising management behaviors I see on the gemba all the time, in a funny way. The cartoons are critical to the discussion as they set the scene, and the text is then a response to the mainstream behavior. It’s like “do you recognize that?” and then “here’s what you can think about as an antidote.” The writing was more intuitive than that, but it’s more or less where I ended most of the time.

RP: You say that Lean is “not about becoming faster or cheaper; it’s about becoming wiser and kinder.” Since we are talking about words, can you tell us what kindness means in a lean context and what role words play in shaping a kinder approach?

MB: Lean is tough, we all know that. Senseis can be impatient, insulting, demanding, that’s for sure. But here’s the thing: they care. They care about people. They care about getting the right results to prosper. And they care about you (although they sometimes have odd ways of showing it)—what’s going to happen to you, and how they can help you overcome the obstacles you face. Wiser is being more competent in context. Kinder is about being more compassionate in situ (not necessarily softer). You go to Japan and you see their cultural discussion is very different from ours, and so is their Buddhism. On the one hand, there are collective challenges that must be acknowledged, and everyone should find their way to contribute. On the other hand, we help each other progress and overcome our difficulties. This mix of challenge and compassion really struck me when I finally got to see Toyota and Toyota supplier plants in Japan, in a unique way compared to other facilities around the world. I believe there is an ethical core to the TPS around this “more demanding, more understanding” paradox that needs to be considered and discussed outside of Japan to grasp the full essence of Lean. We need to be wiser about what products we make, how we work with people and how we use the environment—the cliff we’re driving towards at breakneck speed is not going to go away by ignoring it. But finding the right answers, I believe, also requires greater kindness to our customers, our staff, our suppliers, our locations, so that our solutions are not so extreme and we truly care about their needs and their possibilities. Wiser is about solving the right problems. Kinder is about recognizing how people see their own problems and lending a helping hand, or an encouraging word. An acknowledgement of who they are beyond their jobs. Personally, I see myself fail at both every day, which is precisely why I believe it’s so important to work at it.

RP: The very first paragraph of the introduction references your father. His influence is of course present throughout your body of work. What’s one lesson from him that you still find yourself rediscovering over and over again?

MB: My father… Hmmm. Many lessons, and few of them easy to learn. I think his harshest lesson was that “if you surround yourself with idiots, you’ll become an idiot yourself.” And its follow up, “if you think everyone around you is an idiot, you’ll end up very alone.” It took me many years to see how disciplined he was in who he surrounded himself with to get things done, and many more years for me to see how and why it mattered so much in the end. He once told me a sensei had told him Toyota had four kinds of suppliers: A-list, people they would trust implicitly and whose suggestion they would listen to; B-list, people who they trusted to carry out smartly an idea once it was suggested to them; C-list, people who would execute faithfully if you told them what to do and how to do it; and X-list, those who would screw up anything no matter how well or how long you explained it, and do it in a way that would come back to bite you. This sounds very much from my father’s own interpretation, but it’s probably the most powerful lesson he gave me. What he showed me was to surround yourself with smart people you get on with (more or less) and then communicate constantly about where we are and where we want to be—and how to get there.

The other lesson is to go back to the gemba, of course. It’s nice and comfy in meeting rooms, where you’re surrounded by smart, powerful people (and we all love the sound of our own voices). My father would pull us out of the meeting room and take us to the gemba, where it was never as people were saying. Zoom in into the details, zoom out to see the big picture. How does this machine touch this part? Where is the value for customers? How is the people organization set up (who are the team leaders, etc.)? How is logistics set up? What is the market doing? What is the strategy? How does it reflect on the shop floor? This is the discipline of thinking against yourself—of training your mind to really look and figure things out for yourself. Confirm your ideas, test your hypotheses. He was relentless about that, and he was right.

RP: You close the introduction with an invitation to readers to “walk this path together, one concept at a time.” What do you hope readers will take from the glossary?

MB: I didn’t set out to write the definitive definition of every lean term. I truly believe that you can’t ever know TPS (and TPDS, the lean engineering part; TW, the Toyota Way of its business culture; and the Toyota Way to sales and marketing—the full Toyota Management System), you can only learn it. Each word was an opportunity for me to reflect on what I understand and not understand about each underlying concept. This is what I hope to share with readers. The discussions in the glossary are not an end point, but a starting point. What am I saying that doesn’t make sense to you? Don’t take my word for it—go and find out!

The greatest difficulty with adult learning, I believe, is maintaining the curiosity to go and see where the finger points. Adults know very well how to learn, but most of the time, they simply won’t go and look (too busy, I don’t see how that solves anything, I don’t have access, etc). Similarly, the greatest difficulty with problem solving is the underlying general culture to look at a problem in many different ways, to fit different mental models to the issue until intuition strikes. I hope that readers will take from this glossary the spirit of investigation—and fun—and discuss these terms with their colleagues and their teams: what do they really mean by that? To what problem is this a solution? Why do we so often behave like the guys in the cartoon? My aim was to recapture the sense of inquiry and fun we had in the early days of Lean, when it was new and fresh. Happy holidays to everyone and yes, Lean is awesome, but it’s also fun!

Buy your copy of What’s Lean? Michael Ballé’s Lean Glossary here.

THE AUTHOR

Michael Ballé is a lean author, executive coach, and co-founder of Institut Lean France

Read more

INTERVIEW – Software development company Theodo is a unique example of a digital company that has fully embraced lean and understood its potential. We caught up with their young CEO and CTO.

NEWS - Back from his annual trip to Shanghai, Anton Grütter, CEO of the Lean Institute Africa, shares a few interesting insights into the Chinese culture.

CASE STUDY – This article briefly outlines the different stages of the lean transformation at Mercedes Benz Brazil, as the company looked for the best approach to engage everyone in continuous improvement.

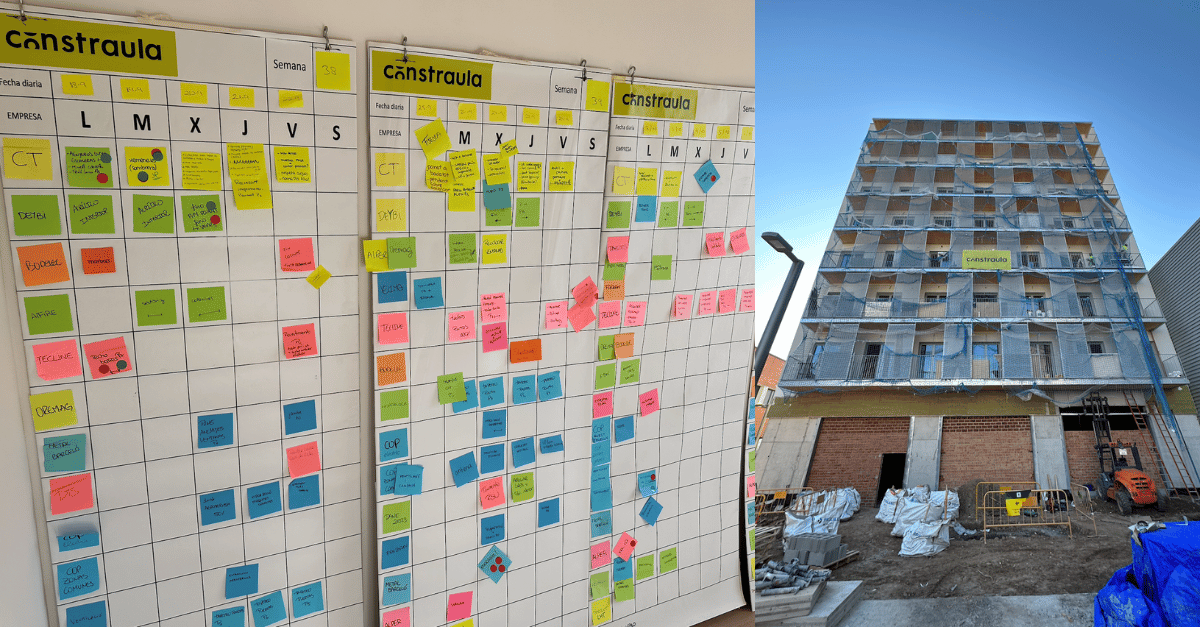

CASE STUDY – Thanks to Lean Thinking, this Spanish construction company was able to deliver a challenging project in one year, well ahead of schedule. Here’s how they did it.

Read more

FEATURE – Many lean initiatives fail because managers lack an understanding of how adults learn. The authors discuss why execs need clear strategies that link improvement efforts to human capital development.

FEATURE – To boost the “adoptability” of Lean and sustain it over time, it’s necessary to develop institutions that support our improvement efforts without making processes more bureaucratic.

FEATURE - Projects or programs? The authors discuss why Lean Thinking should go beyond piecemeal operational improvements, as a transformative strategy that balances today’s demands with future adaptiveness.

FEATURE – To develop a lean culture means to develop each lean thinker and help them reach their full potential. Here’s how Aramis Group does it.