How can we support lean systems?

FEATURE – To boost the “adoptability” of Lean and sustain it over time, it’s necessary to develop institutions that support our improvement efforts without making processes more bureaucratic.

Words: Michael Ballé and Nicolas Chartier

Gemba walks, kaizen workshops, A3 presentations, hoshin kanri – lean initiatives are full of strange-sounding rituals, led by strange-sounding roles, such as “sensei”, “kaizen officer” or “team leader.” At the start of a lean program, these rituals and roles tend to be taken up as part of the lean folklore in a we-will-figure-it-out-as-we-go fashion, but as time goes by and the program endures, it becomes necessary to take a harder look at what these roles truly represent in the organizational setup.

Our book Raise the Bar described how Nicolas Chartier and Guillaume Paoli grew their start-up into a billion-euro business, using lean to fight big-company disease and create a resilient organization focused on maintaining the difficult tension between customer satisfaction and people engagement, and the processes needed to grow the business profitably.

To sum up, the approach we followed at Aramis Group entailed first having the CEO learn the Toyota Production System with a sensei on the gemba, in order to discover the key knowledge points that truly impact the results and then teach other executives to do the same and use the lean tools in their area for repeatable learning. This is a radical departure from most lean transformations, in that it is not led by lean experts and consultants but by the hierarchy itself. It diffuses not by roll-out programs where everyone goes through a bootcamp and then engages in some “improvement projects” (with the associated belts), but by spillover from one executive to the next, one area to the next. In this perspective, the CEO becomes the sensei, teaching their executives how to lead the business in a lean way rather than be distantly involved in a lean program run by a functional kaizen office. The results speak for themselves, as Aramis Group has been able to weather crises like COVID and carmaggedon (no new cars on the market) and even gone through an IPO. Every time, we have come out the other side stronger than before.

Seven years into our lean journey, we have doubled in size and reached over €2.2 billion in turnover. We are now present in six countries. Today’s Aramis Group is a different company, indeed, and lean is recognized as one of the ingredients in this recipe for success.

We started with the steps outlined in The Lean Strategy – double the good and half the bad; develop a culture of problem solving; eliminate waste and reinvest in new offering – but, over the years, we built our own approach from experience. This is based on the following:

- Go to the gemba and look at the reality of situations;

- Visualize processes in a way that highlights problems;

- Teach problem solving and encourage teams to problem solve;

- Ensure that the solutions envisaged align with the overall strategy;

- Promote those who do 1/, 2/, 3, 4/ successfully.

Based on the success we have achieved in the past, we’re confident that this approach works, but also that it is profoundly counterintuitive to anyone who has experienced the mainstream way of doing business. As the company continues its fast growth, we’ve come to realize that we have an adoptability problem – an ugly word that captures the ease and speed with which lean ideas can be accepted, tried, and embraced. Aramis Group is in a unique position where lean is explicitly part of the business model and recipe for success – there is no argument there – but we are now faced with two new difficulties.

- Keeping people who have been with the company a long time energized to continue looking for customer problems and wasteful processes, and fighting to make front-line teams engaged. Once the low hanging fruit have been gathered, routine often sets in and it’s all too easy to think that nothing more can be obtained from the tools and to start doing the activities in a superficial or disengaged way “because we have to”, without engaging heads or hearts in finding more value.

- New people are hit with the group’s own lean vocabulary and practices, and the worldview gap between where they worked before or how they were taught at university and the culture we’re seeking to establish at Aramis grows as time goes by. At the same time, experienced executives who have learned how to teach their teams in the early days are now diluted in the larger organization and face a profound challenge inherent to Lean Thinking: the tools can be trained one-to-many, but lean awareness and judgment needs to be taught one-to-one.

This leads us to the key question we’ll try to answer in this article: how do you institutionalize Lean in a company without further bureaucratizing existing processes? What kind of lean systems or institutions do we need to support improvement activities, without burdening departments with meaningless demands for pretend-kaizen, or generating cost-cutting activities that are disguised as kaizen? These are very real issues.

As we progressed on our lean journey from our early shop-floor discussions on why cars were not flowing faster in our historic plant, we have set up a few “institutions” the company did not have before:

- Sensei: executives are encouraged to find their own lean sensei and conduct gemba walks with them. This is neither easy (there aren’t many lean sensei around) nor comfortable, as sensei rarely agree amongst each other, but it is a necessary step to get you to face the problem you don’t want to see – the proverbial elephant in the room, which everyone is carefully treading around. As an experienced lean practitioner, the sensei will make you see the problem (which sometimes means heated discussions) and show you a possible direction to tackle it, but they will not solve the problem for you. You will need to figure it out for yourself, in order to learn.

- Gemba walks: going on gemba walks with a sensei has led us to structure executive gemba walks across the company. Executives will schedule go-and-see sessions to check with teams on the ground how the work is progressing, what problems they are encountering, what decisions need to be made, and how they can help. Gemba walks need to be organized, and the practice itself requires learning (invitation, meeting set-up, asking the right questions, encouraging the teams, etc).

- Team leaders: we’ve come to realize that the bottom-up lean productivity model (safety, then quality, then lead-time, then cost absorption from volume) rests squarely on team leaders and their ability to work with their teams on detailed issues. Team leaders are not managers, but operators willing and able to take responsibility for kaizen. Team leader is not a role that typically exists in mainstream organizations, which is why it needs to be carefully sketched and nurtured.

- Kaizen office: we’ve used many Toyota-born techniques as scaffolding for problem solving and kaizen, both at local level with production analysis boards, kanban, kaizen study groups and so on, and at executive level, with A3s, obeyas, material and information flow analysis, etc. These many activities need to be supported and organized.

- Communities of practice: to accelerate the learning and share experiences, we set up several communities of practice starting with a “connect our brain” initiative at top leadership level. This has led to developing several other guilds to share awareness of problems and knowledge points across countries.

- Talent review: seeing the benefits of having more lean executives have led us to realize the importance of looking more closely at career paths. Some middle managers have a good sense for business solutions, but little interest in lean. Others study lean assiduously, but struggle to turn their understanding into insights and results. We ended up having a closer look at who moved up through the organization to try and promote people with both an interest in lean and a solid business sense.

These new institutions have become necessary as we strive to support lean at scale. The heart of the problem is that, as executives familiarize themselves with the lean language, concepts and practices, they find it hard to link those to their present business issues and decisions to make. They see business problems that they’ll solve with business solutions, and then learn to identify different “lean problems” – poor customer service, no built-in quality control, work stagnation, lack of standards or engagement from team, no TPM, bad 5S (probably the first thing they learn to spot) – which they then try to solve with lean tools. The real aim, however, is to get them to recognize business problems and solve them with Lean Thinking.

This is more of a radical change than one would think. It needs to be tutored carefully. Experience shows that people tend to be thrown into the deep end and either sink or swim, which is rarely very efficient. We feel they could be better tutored to the link between business problems and lean countermeasures. For instance, in the factory, one executive can see a problem in the flow of cars through the facility, but not the overall amount of stock being held in the plant and showroom vs the daily flow or sales. Vice versa, another leader could be trying to reduce her total inventory to meet group targets without seeing the inflexibility points in her operations.

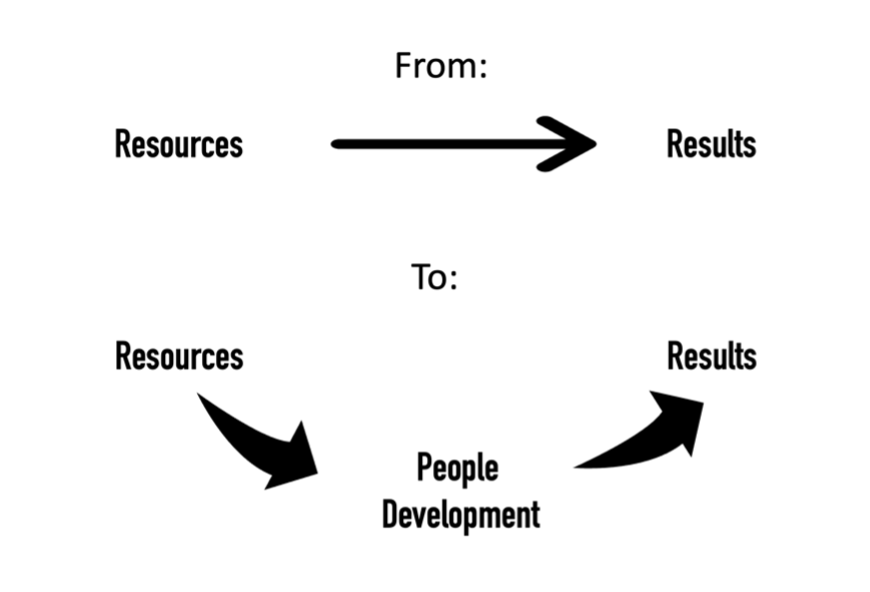

It turns out spillover (rather than corporate-led roll-out) is very powerful. In our two latest acquisitions, the CEOs started on their own problem-solving activities, A3s, kaizen and competence matrixes. They took these initiatives from visiting other sites with a longer lean history and without sensei or kaizen officer to implement the tools. This is really encouraging and at the heart of what we try to do with lean. Rather than simply obtain results from resources, our aim is to develop people to achieve a more effective use of resources with less waste from poor understanding of business situations and poor decision making:

However, we also know from experience these thinking tools are not always intuitive and need to be oriented. At some point the sites will need support in building the tools the right way in order to sustain an ongoing learning curve.

When we first started with lean in earnest in Aramis Group’s original factory, both CEO and sensei focused on problem awareness: recognizing problems, facing them, framing them in the best way, and seeking countermeasures from local teams – as opposed to coming up with managerial “solutions” for people to execute. Indeed, based on The Lean Strategy, our first effort led the management team at the time to distinguish a “4D” problem solving (Define, Decide, Drive, Deal) from a “4F” lean thinking approach (Find problems, Face them, Frame and Form solutions from kaizen). We didn’t realize then we were in fact building basic skills in problem solving: what is a problem? Who needs to be involved? What is normal process behavior? What are the functional factors? What constraints can be tested? How do we know the problem is solved? And so on.

Then we adopted Toyota’s A3 format to share problems among ourselves, so people could better explain their reasoning and the actions they proposed. The management team learned what an A3 should look like and how to build one. We constructed the A3 tool – without quite realizing that we were doing so. It just seemed an obvious thing to do.

With everyone having practiced A3, we then started to focus on making sure we had meaningful A3s: is this an important topic? What is the business impact? Are you sure you’re solving the right problem? What will this imply in both business results and the way the company works? And so on. We were learning to use the lean A3 tool to achieve visible business results (which came in very handy in the market crises we had to face).

Getting better at using the A3 tool on impactful decisions, we could then go on to share how we used the tool both internally and, to some extent, externally to spread our lean culture – to accelerate the spillover.

Once the executives have the tool well in hand (because they’ve built it in their area), you can start asking them to apply it to more demanding business issues and propose different kinds of decisions than they would have made in the past. This is not an easy transition. In many lean programs, lean tools remain at the lean concern level – which gets tiresome. After all, how much 5S can one do? Or counting kanban cards? Yes, it is essential to maintain the discipline, but maintaining interest requires linking Lean Thinking to clear-and-present business problems. First you build the tool, then you use it. Ownership of Lean through “change how you act so you change how you think” truly comes together when people apply lean tools and thinking to impactful business decisions and see better outcomes.

At this point, communicating how decisions are made in the business becomes essential for the spillover of lean culture, so that people can see that we do indeed take executive decisions differently – while understanding some decisions that might appear counter-intuitive to them in their daily work. Communicating to share and to explain, both internally and externally (particularly today, where boundaries are increasingly porous), is the secret to widespread adoption of a different kind of thinking. Once you’ve familiarized yourself with what Lean Thinking considers a problem (and what not) and what is a lean response to it (and what not), you need to explain this again and again to others who have had a different journey and continue to operate within a traditional business mindset.

Climbing this ladder won’t happen on its own, which is why you need lean institutions, such as sensei, kaizen office and team leaders, as well as workplace tools, like kanban and A3s.

The issue that people who are new to lean face is that our systems are currently in place and so are the institutions that support them, but they still must use the tools while their basic skills have not been developed, and they have not participated in building the tool. Worse, this does not happen only with a high-level tool like the A3, but with all our tools – as in 5S, quality boards, kanban, dojo, and so forth. Someone new to lean is simultaneously faced with being asked to use counter-intuitive tools by the institution we have grown to support the tool – their leader’s gemba walk or the kaizen office inviting them to a kaizen event, etc. The people staffing these institutions need to be developed, as well. The overall scheme looks something like:

We believe the core of our adoptability problem lies in the fact that we expect people to use tools the organization has developed and generalized without either checking that their basic skills are in place or that the person has built the tool to some extent (or that they have played with it in a sandbox enough to feel comfortable using it on real-life business issues with potential impact). Basic skills are in and of themselves not so obvious to pinpoint. From our work on the shop floor, this is what we look for in our people:

- Technical skills: Knowing the job and understanding how their tools interact with their materials to produce customer satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) and at what cost – also understanding that getting the job done means improving safety, quality, timing and cost of the work.

- Seeing and listening skills: Being able to look at a situation and hear what people say about it and build a picture of the problem in their minds, beyond what they originally thought. This sounds obvious, but it turns out that seeing and listening skills are quite rare and can always be worked on (particularly in terms of seeing safety, quality, lead-time or cost issues, as well as recognizing enthusiasm or distress in people).

- Problem-solving skills: Being able to recognize and pinpoint a problem, then draw a functional analysis (how things are supposed to work) in order to spot where things are not working, knowing who to talk to about it and how to start looking for countermeasures is also a basic skill, although when you look at it it’s not that basic and needs constant learning and honing.

- Teamwork skills: Some people are easy to get along with, others less so. Keeping a team task-oriented while being aware and open to members’ individual moods and personal difficulties is a skill that involves both emotional empathy (being attuned to others) and cognitive empathy (seeing what they’re trying to achieve) and how to switch from one to the other – as well as knowing when to follow, when to organize, and when to lead.

- Communication skills: Getting one’s point across by expressing ideas clearly and concisely, as well as attentive listening to staff’s concerns and suggestions, conveying to them the importance of their job and making sure to share changes that will affect them. Simple conflict resolution skills, such as making sure people feel heard and checking facts before jumping to conclusions, are critical as well.

- Looking ahead skills: This again sounds simple enough, but it is yet another basic skill people need to develop in order both to understand how things work and evaluate possible countermeasures according to impact. The ability to anticipate problems – both on tasks and on people’s reactions - is an essential part of problem awareness and managerial potential.

- Leadership skills: Discovering opportunities, taking initiative and negotiating the support needed to get things moving is another basic-yet-difficult skill required to function within a lean framework and use its tools. Without this skill, tools can turn into formal activities with very little value.

Of course, one can think of many more “basic” skills than this set of seven. Yet, without minimal proficiency in these skills, problem-solving and kaizen initiatives can easily turn out to be misguided or fraught with interpersonal friction. Once the basic skills are in place, however, we can then turn to building the tool with the person – explaining how the tool works to do what – and have them practice, until we can use the tool on real-life, complex problems.

Adoptability is at the heart of sustaining a lean culture over time, beyond the early excitement of setting it up. Nothing fails like success: it is precisely because tools have been explored and deployed earlier on that they fail to work later on, as new circumstances set in and different people join the organization. Without basic skills, it’s hard to see what or how the tool can help. Without a clear understanding of how the tool is constructed and what it does when applied to a work situation, it feels risky to try it on any instance with something really at stake (as opposed to handling it as we’ve done in the past). Without positive experiences with the tools in situations that mattered – kanban for cars in the factory as opposed to kanban for office supplies – it’s hard to share and communicate a tool and its potential.

There is no magic solution (if there is one, we haven’t found it, anyway). We know from experience that a lean transformation delivers the results we want, but we also know that it is hard work and that, as we described in Raise the Bar, pushback, backslide and setbacks are as much a part of the journey as sudden progress can be. We’ve also concluded that a major cause of backslide is using a faulty tool on a business problem. In this case, where you had one issue, now you have two: the problem you wanted to solve, plus the problem caused by the tool. This, at least, we think we can fix by rebuilding tools from scratch: starting with basic skills, then moving on to building tools through practice in known situations, and then using them on real issues – ultimately sharing these experiences and communicating about them to feel the culture and grow together.

To support or, more precisely, to scaffold a lean culture, we need institutions – things like conducting gemba walks, working with sensei, setting up a kaizen office, and so on. But we also need to have a clear theory of what these institutions should do and how they’re likely to work in new settings, and with new people. Sensei will push you to face the problems you’re uncomfortable with; kaizen officers will support visual management and organize study groups; team leaders will support their team in their daily operations and encourage kaizen initiatives. These new roles must be supported by specific organizational functions to develop knowledge and continue to be effective without sliding into bureaucracy. By having a clearer vision of how to build and use lean tools, we can hope to increase adoptability and use lean theory and practice to truly build both human and social capital – thus being able to deliver the results we are after.

THE AUTHORS

-p-500.jpeg)

Read more

FEATURE – To speed up the issuance of insurance policies, a SulAmérica department decided to move away from big batches and start working in flow.

FEATURE – This story of a lean application in elderly care in a Norwegian borough demonstrates the great strides that can be made in providing better service to citizens if their needs become the focus of the work.

ONE QUESTION, FIVE ANSWERS – With this month’s question we try to understand what lean idea or principle our interviewees would have liked to learn sooner or better in their journey. So, heads up… You might be in a similar situation.

CASE STUDY - A pioneering school in Rogaland, Norway, is proving that some elements of lean thinking can successfully be adapted to the education system to create better conditions for both teaching and learning.

Read more

FEATURE – In this article, Michael discusses the four levers that organizations can work on to thrive in good times… and bad times.

FEATURE – To get the results we want from a system, or prevent it from generating undesirable events, we need to understand how it works and behaves in the real world. That’s exactly what Jidoka does.

FEATURE – When it comes to the fight against climate change, we can’t expect to achieve much until we fundamentally challenge the way we think about resource consumption. Lean is our tool to do that.

FEATURE – Nobody understands humans as well as humans do, and Jidoka is the key to learning about your customers and create ever-better products and services.