New Year loss and found

FEATURE – 2019 was another momentous year for the Lean Community. John Shook reflects on what we lost and what we gained in the last year of the decade.

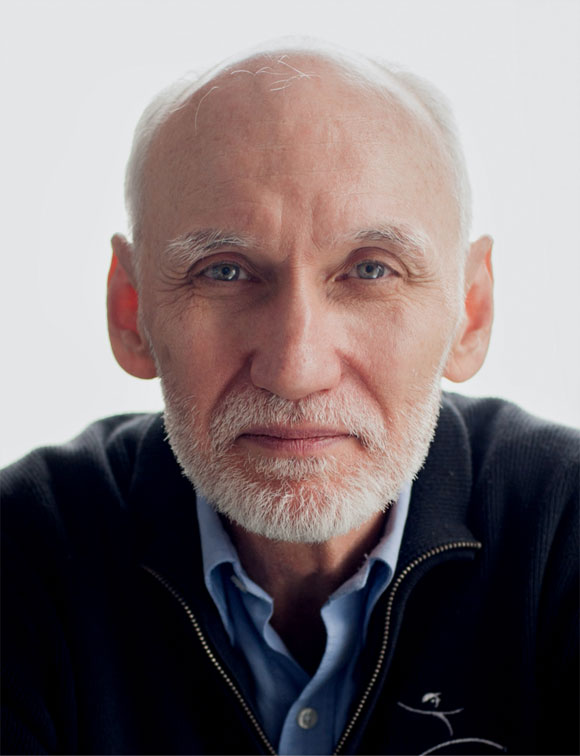

Words: John Shook, Senior Advisor, Lean Global Network

As many of us are wont to do, I reflected a bit over the holidays. As always, it wasn’t hard to find ample fodder on both sides of the hope vs despair ledger: we have so much cause for concern around us, but also plenty to rejoice about. Loss and gain, as always. I’ll share a loss first, then some new hope.

Takehiko Harada, a close collaborator of Taiichi Ohno and contributor to the development of TPS, passed away on November 24, 2019. Joining Toyota as an engineer in machining in 1968, Harada entered the company just as TPS was – according to many, including Ohno – reaching a “mature” state. Ohno had just formed his Operations Management Consulting group, which would take on a critical role in the diffusion and ongoing development of TPS for decades to come. Early in his career, Harada developed a close sensei-deshi or mentor-mentee relationship with Ohno and eventually became a project general manager (shusa) of OMCD.

While TPS may be said to have reached something of a “mature” state by the time Harada began his own TPS journey, there were certainly many important developments still waiting to happen. Harada was a direct contributor to some important ones, especially in the realms of supporting workers and in creating flow, which was in his view the operational aim of TPS. One of his simple yet highly practical inventions was the “chaku chaku switch” or the start switch that enables workers to simply flick on the fly as they operate a u-shaped cell or any chaku-chaku line. This supported workers to work in a natural rhythm, in a flow.

Another of Harada’s contributions became one of the bigger developments in Toyota’s production system (if not TPS) of the past couple of decades, in the form of the ubiquitous application of SPS – the Set Parts System. SPS is Toyota’s modern, lean spin on an old technique – kitting – that puts kitting on steroids and integrates it with its entire and all-important (and still little understood outside Toyota!) system of heijunka production planning and control.

During his stint starting in 1999 as president of Toyota’s assembly operations in Taiwan, Kuozui Motors, Harada worked with local production manager Joe Lee and the team there to introduce SPS as a major system kaizen. There was a specific need (a problem to solve) that Harada and Joe needed to address: line-side space constraints in the face of increasing model complexity. The Kuozui plant was originally designed for simple CKD assembly of one basic model (the Corolla). But conditions at Toyota in meeting global customer demand resulted in the parent company asking Kuozui to produce a variety of models, including the Corona, a second line for the Tercel, and later the Camry. Additional volume is always welcome (if you’re going have a problem, too much work is better than too little), but there was no way of adding to existing operations additional models with their completely different sets of supply components that would need to be placed lineside. Workers couldn’t complete their standardized work with “one pitch, one return”, as parts and movements would spill over beyond their workstations.

Months of planning, trial-and-error and improvements big and small led the team to move most components and materials away from the assembly line to a central area where they were sequenced for direct delivery to the point of use, at the time of use (per the aim of JIT: right part at right time in right amount). Then, additional benefits emerged that had not been anticipated by Joe and his local team. By virtue of having no parts to obstruct vision and movement, the line side opened up, as a parting of the sea. The entire plant floor looked and felt radically different. The new highly visible environment led to ideas for even more improvements that would never have emerged under the previous conditions. Kaizen flourished. Joe Lee wrote this retrospective of Harada-sensei (sorry, Chinese only!) with the intriguing title of “The embankment collapses on the ant’s nest” on the Lean Enterprise China website.

Toyota execs came and saw. And they liked what they saw. So much so that they decided they needed to share the wealth, the potential of the idea. In the ensuing years, TMC dictated the spread of SPS throughout its global system of factories. The advantages were too great to allow them to be limited only to Taiwan. While understandable, issuing the edict that all plants would implement SPS also meant that many plants would now be installing a solution that made imminent sense for Kuozui (Kuozui needed the space) even when space constraint was not an immediate concern. It became an interesting case study in addressing the question of when you should require common practices versus allowing each operation to develop their own solutions to their own problems.

My direct interactions with Harada-sensei were few, but filled with generous sprinklings of invaluable insights. We are fortunate that Harada left behind his excellent book Management Lessons from Taiichi Ohno. It is written in what you might call an “old TPS sensei style”, one effect of which is that it places demands on the reader. You can’t read it passively, expecting to jot down a list of facts to remember or tricks to implement. Rather, it demands you read it looking for nuggets. Such readers are rewarded, though, with a wealth of insights that only reveal themselves through addressing the questions inspired by the face value of the stories and lessons. Jon Miller wrote this helpful review.

Harada-sensei had much to say about how to facilitate the adoption of TPS outside Toyota. If I try to sum it up, he believed it was important to explain the why behind the various artifacts and actions that are required to create what he called a “wonderful operation”. Leaders need to consider and practice how to explain fundamental thinking and practice in simple and concrete terms. Harada was a believer in the importance of asking good questions and, also, the importance of answering any question thoughtfully, patiently, showing respect to the questioner. “Explain in a way people feel respected. If you show respect, you can earn trust. Answering questions in a respectful way is a great chance to create harmony.”

This year’s reflection confirms what I’ve found over many years: when seeming to lose something of great value, if you look you can find that something new has come along to offer welcome and perhaps unexpected value (even if it’s not a “replacement” for what was lost, and certainly the following are no replacement for Harada-san). For that, as I look back over the past year (I’d be curious to hear what you might point to), I see promising progress being made to reconcile or even unify some divergent trends. I receive regular questions from confused individuals regarding the relationship between lean thinking and the disparate, yet related trends of digital transformation, agile/scrum, and Industry 4.0. What, indeed, is a useful way to view these approaches to organizing work?

The topic has been the subject of entire conferences. Marie-Pia Ignace and her team at the Institute Lean France have been exploring the topic with increasing depth for years (and will no doubt continue at their upcoming Lean Summit in Lyon on March 23-24). The Lean Institute Brasil has joined the digital party with sizable and substantive events. I was able to join the 2019 event last September, along with two important pioneers (both named Nigel) who are making great strides at bringing the lean production and agile/scrum worlds together: Nigel Thurlow, head of agile at Toyota where he is working to bring agile and TPS together, and Nigel Dalton, chairman of the Lean Enterprise Australia.

As a noteworthy attempt to shed light on the lean and digital muddle, I turn to Christoph Roser’s Industry 4.0 Discovery Bus Tour of Geeks. Christoph rented a bus and invited interested parties to join in a tour to try to figure out exactly what is all this noise about Industry 4.0. The Geeks visited 10 German factories that claim to be doing exemplary work, with Christoph blogging about the visits along the way. In response to my query “Exactly what is Industry 4.0?”, Christoph offers this summary of his findings:

“It is pretty easy to answer what Industry 4.0 is: it is a German Government Research Program. Beyond that it apparently can be anything you want it to be (as long as it includes computers). But I agree this is a pretty unsatisfactory answer. I think the feeling of being underwhelmed comes (for me at least) from being promised a lot of magical stuff, only to receive a normal computer and a lot of effort to make software work.” I encourage you to read the entire series of posts on his blog All About Lean.

2020, like 2019 and the decade that preceded it, will bring losses and newfound gains. But labeling anything a loss or gain is up to us – we choose to learn and move forward, or not. The only thing for certain is that more change is surely on the way and the important questions to ask are what changes do we want and what actions will we take to realize them?

THE AUTHOR

Read more

SERIES – The authors discuss the fifth of six elements in their 6CON process development model – CONfirm – leveraging a robust launch readiness approach to finalize the process while ensuring it meets the targets set in the business plan.

CASE STUDY – Here’s the story of a mature lean company from Michigan. The author tells us about Zingerman’s Mail Order’s lean transformation, their challenges and their successes.

FEATURE – In this article, we learn how a simple andon system and lean problem solving helped Theodo move past some of the most common obstacles that Agile alone can’t overcome.

CASE STUDY - In the past two years, the Consorci Sanitari del Garraf near Barcelona experienced a lean turnaround. The author gives us an overview of the key building blocks of this transformation.