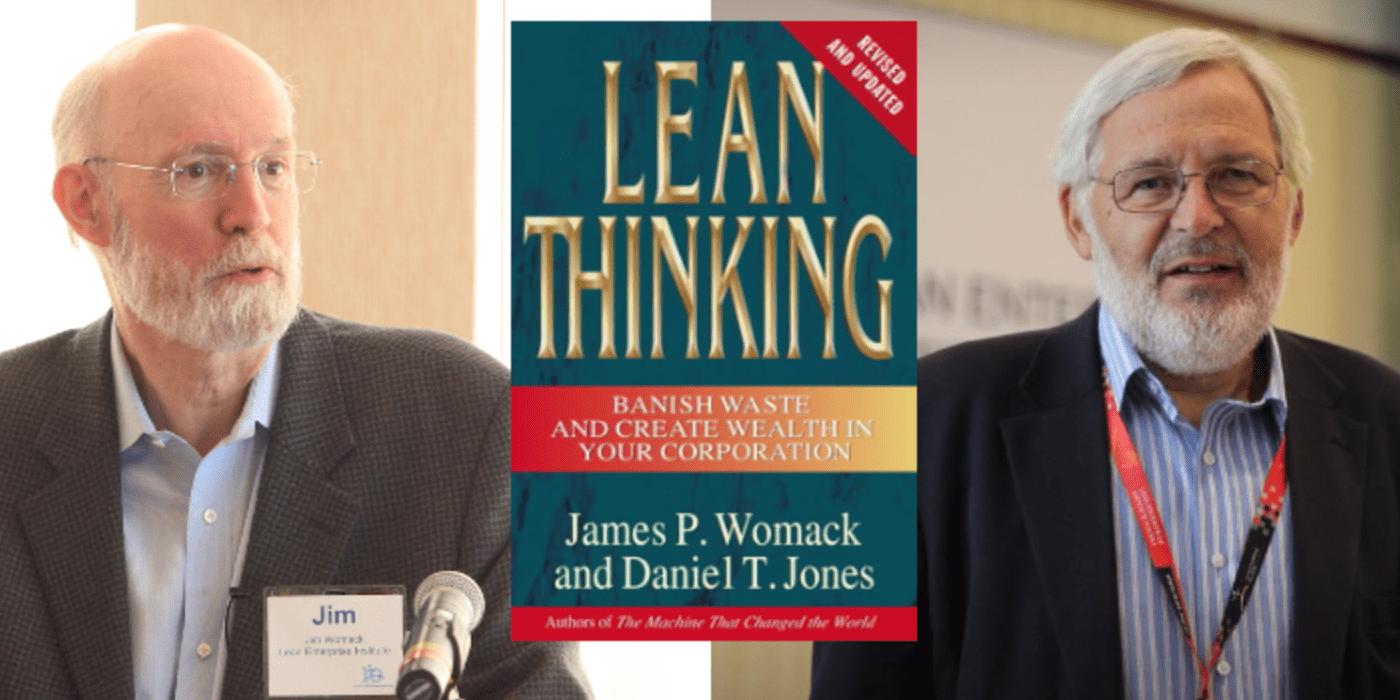

Writing Lean Thinking - the authors look back

INTERVIEW – Twenty years ago a book started a movement that is growing stronger every day and that has changed the world in many ways. We caught up with the authors to sneak a peek behind the scenes.

Interviewees: Dan Jones and Jim Womack, co-founders of the lean movement

Interview by: Roberto Priolo, Editor, Planet Lean

Roberto Priolo: This month marks the 20th anniversary of the publication of Lean Thinking. The importance of this book for the Lean Community can’t be overstated, but it would be interesting to hear what the authors think about the impact it had.

Jim Womack: As an author, you can look at the number of copies you have sold and, in the case of Lean Thinking, that is certainly satisfying. However, this tells us nothing about the actual impact of the book. What we need is data on how many readers used the ideas in the book to sustainably improve their organizations. And that’s hard to collect.

Our aim was to give people a license to try something new. That’s why we structured the book the way we did, in three parts: a simple explanation of what lean is (the five principles); examples of its application in different industries and countries (to show that this methodology is not only applicable to automotive companies and to Japanese culture); and an action plan to give people the courage to give it a try. Looking at how widely spread lean practices have become across different sectors it would seem that Dan and I have at least encouraged many people to make that leap of faith.

Dan Jones: The interesting thing is that we didn’t know quite what we would achieve with Lean Thinking as we launched it in the fall of 1996. After all, the success of The Machine that Changed the World in 1990 had been a surprise in itself! As Jim said, with Lean Thinking we wanted to build on the platform Machine gave us and show the opportunity for organizations to go down a different path. I believe that the book succeeded in particular because it spoke to people who were struggling with the challenges brought forward by globalization (like Chinese competition, for example) and with making things better at work to engage a new generation of employees with different expectations about involvement. In that respect, we achieved what we had set out to do.

What we didn’t know was that we had created a movement. That was a total surprise to us. We had been organizing and participating in small lean conferences since shortly after the launch of Machine but as readers began to apply the advice in Lean Thinking attendance mushroomed. We suddenly realized that we were creating a movement and this encouraged us to found the Lean Enterprise Institute in 1997 (followed by the Lean Enterprise Academy and then the Lean Global Network) to help create a stable, supportive community for lean thinkers. This unexpected consequence of Lean Thinking was truly energizing.

RP: How did you see the understanding of lean evolve over time?

DJ: We knew that not everybody would be able to make the same leap of faith that Art Byrne (Wiremold in Chapter 7) and Pat Lancaster (Lantech in Chapter 6), had made, and that people would need a set of tools to act on the action plan. At first, people plowed through the tools and, for a long time, they believed that the toolbox was all there was to lean. This was the driving force behind the proliferation of lean consultancy firms across the world applying tools justified by rapid paybacks. But I think this was a necessary step to establish the movement and later come to the realization that it is up to management to make lean a success. Now we have gone further, talking about lean as a strategy and a learning process for leaders. We are on the cusp of answering a lot of questions, and we couldn’t have done it without this movement, or without its mistakes.

RP: If you could go back, what would you do differently?

JW: The intent of Lean Thinking was revolutionary. The idea of applying the concepts of kaizen and kaikaku across organizations in a short period of time – with the promise of a complete turnaround – inspired many people, particularly those working in large organizations, who were used to seeing no change whatsoever. We told them to ditch the improvement meetings and go to the gemba to try experiments instead.

The book was not as helpful as it should have been (only as helpful as we could make it) with regards to management. It encourages readers to organize their activities by value stream, but doesn’t tell them how to mediate across the vertical functions that were assumed to be unnecessary. In many ways, Lean Thinking is not a management book, but an ideas book about creating brilliant value streams to solve the customer problems. It tells you that if you focus on the customer and work backwards to create a process that provides the customer’s desired value while eliminating large amounts of waste, your business will thrive.

We didn’t give people any advice on how to sustain either. For example, there is no discussion at all about creating the basic stability that is the necessary foundation for sustainable kaizen Dan and I had never been managers and assumed that managers in most organizations would have the energy and ability to sustain results. It turned out they couldn’t, and that the management systems of most companies were designed to do re-work on top of chaos, not to sustain kaizen gains. We didn’t give any advice on this problem because we weren’t aware of it. Each company we featured was in the midst of a profound lean transformation and thought they had won the war.

DJ: As writers rather than managers, Jim and I could only write what we saw other managers do during our research. Indeed, we assumed people would want to figure lean out by themselves; instead, we discovered they wanted us to tell them what to do.

It’s true that we emphasized the value stream dimension, but I believe that was a fundamental wake-up call because it told people that successfully thinking end-to-end depends entirely on how engaged in problem solving your people are. In this sense, we created the basis for further learning – which came in the following years as we studied lean in different environments and added more pieces to the jigsaw puzzle.

RP: Is building capability in people the most important lesson that can be drawn from Lean Thinking, then?

DJ: Absolutely. Lean is a people-centric solution, not a people-free solution. Taylorism was about building a system, designed by experts, which any fool could operate, while lean is a management system centered on people and growing out of the gemba.

RP: Were you two ever in disagreement over the book, its content or structure?

JW: Dan and I were absolutely of a mind about what to do. At the time, we both had day jobs to pay the mortgage (Dan was an academic and I was advising the leadership of big organizations) and we both had little kids, so our issue was actually finding the time to write the book as a night job. Our rate of progress was the only conflicts we ever had. I’d say: ‘Dan, where is chapter 6?’ to which he would respond, ‘Jim, where is chapter 7?’ to which I would respond, ‘I had a bad month’ to which he would response, ‘I had a worse month.’ And so on. But we got there.

RP: Dan, as you two wrote the book, what was your forte? What about Jim’s?

DJ: I was thinking more about the principles, while Jim – who is a great storyteller – was marshaling the cases that would illustrate the principles. Ever the skeptic, he always wondered what the best way to provide the evidence would be.

Not many people know this, but we actually ended up turning the book around just a few months before it went to press, putting the principles first and the cases right after. I think the strength of the book actually lies in the clear logic behind its structure. It was a busy Christmas, that one in 1995, with drafts being faxed (or were we e-mailing by the end?) back and forth across the ocean.

RP: It must have been really helpful for you both to discuss and bounce ideas back and forth.

DJ: Absolutely. In fact, the biggest insights came out of our discussions. The value is in the debate you have with your co-writer, and I believe this is what makes the book so rich.

JW: We had an excellent balance in our way of working, and a wonderful relationship. Dan is a born optimist and a big-picture guy, while I am a born pessimist and obsess over details. Perhaps most important, he was the one who gave us the courage to keep going when we got bogged down.

RP: Can you tell us about the research work you did as you set out to find examples of lean around the world?

JW: After we wrote Machine, we had no reason to believe lean would ever be anything but an approach used in automotive, or that anyone was doing it, for that matter. We knew that it had succeeded at NUMMI (The Toyota-General Motors joint venture in California), but except for that there was no evidence of lean being implemented anywhere except in some Japanese greenfields in North America and Europe. (Remember that not all of the Japanese companies were lean; we even got a call from one wanting advice on how to turn the mass-production mess they had created in their US greenfield into a Toyota-style lean success.) We were determined to write about how to apply lean thinking everywhere and this meant we had to find people who were actually doing it and we needed to find them in non-automotive industries if we were going to show general applicability.

We didn’t have websites to go to back then – the Internet was in its infancy – so we went to see the early consultants in the field, like TBM and Shingijutsu, and told them we were looking for examples for a book. That’s how we found United Technologies, Wiremold, Lantech, Porsche, Showa and the other companies we featured.

Because they all had different sensei, most of these organizations had never talked to one another. I still remember the first time we brought them all together in a conference at the Kennedy School at Harvard. As unnatural as that meeting felt at first, it didn’t take long for the attendees to understand they were all talking about the same thing – despite the different traditions and backgrounds. We gave them a neutral ground on which they could discuss and learn from each other, and a way of feeling part of a big movement.

Our approach was to never be too prescriptive. As exasperating as this was to our orthodox Toyota friends, we have always believed that experimentation and an open mind to try new things are more important than having read the Scriptures. Instead we’ve said, “Let’s go to the gemba, collect some data and let the evidence speak”. And that’s what the examples in Lean Thinking did.

RP: You must have so many stories from your research trips…

DJ: Indeed, like that time in 1995 we were nearly wiped out in the sarin attack in the Tokyo subway.

RP: I’m sorry… What?

DJ: We were visiting Japan to gather evidence for the book and the Shingijutsu team was taking us around. On that day, we were travelling on the Tokyo subway and missed the attack by a few stops. As you can imagine, this made a big impression on us and made us allergic to anything about lean that starts to sound like a cult.

JW: There were great times, too. We did hitch a few rides on corporate airplanes to visit allegedly model operations during our search. These visits sure were fun, especially as young researchers… but they were mostly muda in the end as the high-priced help with no gemba knowledge drops in from the sky to tell local managers what to do. And, most of the organizations who thought they belonged in a book actually hadn’t done anything sustainable of significance.

DJ: Don’t think it was that glamorous. I distinctly remember the scar Jim got after gashing his bald head in one of those small Japanese showers as we prepared to go to Toyota City for an important meeting. He was definitely too tall for Japan!

RP: What about the Shingijutsu team? Some of them are legendary figures…

JW: The Shingijutsu guys were very interesting for a number of reasons. To begin with, they had worked directly with Taiichi Ohno. Secondly, they had done brownfield transformations of Toyota suppliers in Toyota’s mad rush to bring its supply base up to its lean standard after sales took off with the Corolla in 1966. So they had both the lean knowledge and a tested transformation method! The latter came in the form of the magical five-day kaizen. They would take an area of a factory or office and transform it within a week by introducing cells and one-piece flow (so it was kaikaku more than it was kaizen). It was a brilliant technique, but it was incomplete – you have to kaizen and kaikaku both the value stream and the management at the same time if you are going to succeed, but there was no method for the latter. This task would be written down in the “Kaizen newspaper” left behind after each event. The problem was that no one ever read the newspaper.

The Shingijutsu team achieved impressive if often unsustainable results every time, which made them very popular consultants. And their theatrics made them legendary figures people still talk about. They claimed not to speak English and – when in character – were only accessible through their interpreters. And they asserted – indeed, shouted – that clearly impossible things could be achieved within clearly impossible timeframes. Their confidence and bravado was such that in many companies the managers actually achieved the impossible. As Chiro Nakao once told me about working with Ohno, “It was easier to do the impossible than to explain to Ohno why it was impossible.” And Shingijitsu by channeling Ohno often achieved the same results.

The radical change they promised went against every company policy and every managerial mindset and, at times, it went beyond sanity. But it often worked (at least as long as they were present). I don’t apologize for having been impressed by those guys, but what they did was not sufficient… and, in hindsight, it was often not necessary.

DJ: The interesting thing was that when you talked to them privately, they were perfectly sensible. Their theatrics shocked people, but they fully understood that they were theatrics used to move organizations off deadcenter. What we did learn by hanging out with Shingijutsu, however, was that we could be blunter with management than we would otherwise have been. (Over the years, this also got us thrown out of a few places after we told senior management exactly what we thought of their lean efforts. But this was probably just as well since these organizations subsequently did nothing).

RP: How long did you spend researching and writing the book?

JW: In total, it took us three years to put the book together. It was hard work: I’d go to Pratt almost every week while writing that chapter and Dan went to Porsche a lot as well (he does have a soft spot for trying to improve the Germans). In the end, I wrote the three American cases, Dan wrote the part on Germany, and together we worked on the Japanese examples.

RP: The reporting style you used to write Lean Thinking was certainly a departure from the academic tradition. What did it teach you about communicating lean?

DJ: While writing Machine, Jim and I became very cynical about the academic publishing business. We wanted to truly make a difference and found the academic world to be far too stiff to let that happen: we found that it would be much more interesting to talk to real people doing real work. We saw something that could change the world, and we pursued it. Lean is all about practice and experiments, which we wrote about and interpreted. I think that the fact that academia is only now picking up on Lean Thinking says a lot. (They loved Machine, by the way, because it presented lots of data about the past that professors could endlessly analyze without needing to leave their offices.)

JW: There is an enthusiasm in the book that was judged inappropriate by the academic world. Dan and I were (and still are) guys on a mission to improve the world – not just to describe and analyze the world as academics do. We found that the best way to do that was to find empirical evidence, anecdotes, and examples that proved that it was possible to manage in a very different and more effective way. Sadly, academia was much more comfortable with theory and with studies using large numbers of examples for statistical analysis. This means there is always a perceptual gap and a time lag with reality in their work. The view from the rearview mirror.

RP: Where do we go next as a movement?

JW: In Lean Thinking we wrote about companies that we thought had won the war. We believed that mass production was a thing of the past, but of course the reality is very different. Modern management and mass production mindsets are still rampant and, as much as we have looked, we have not been able to find that second poster child yet – a new Toyota, so to speak. We now realize we have to help create the model lean enterprise of the future.

DJ: There is much more to lean than we originally thought and, so long as we keep digging and learning, we can rest assured that the movement will keep growing. I believe we have been too inward looking for too long: dismissing the startup and digital worlds, for example, was a mistake. Jim and I will keep encouraging new thinking based on new experiments.

Have you read Lean Thinking?

If not, find it here: US, UK, Europe

THE INTERVIEWEES

Professor Daniel T Jones is co-author of the seminal books The Machine that Changed the World, Lean Thinking and Lean Solutions; and co-founder of the lean movement. He is founding chair of the Lean Enterprise Academy in the UK.

Management expert James P. Womack is the founder and senior advisor to the Lean Enterprise Institute. During the period 1975-1991, he was a full-time research scientist at MIT directing a series of comparative studies of world manufacturing practices. As research director of MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program, Jim led the research team that coined the term “lean production” to describe Toyota’s business system.

Read more

INTERVIEW – Our editor chats with Lean Houses for Dragons author Sharon Visser. They discuss her book, what fear can do to a transformation and the power of storytelling.

FEATURE – In the third article in his series, Christoph Roser provides a practical guide to understand the most adequate pull system to your circumstances.

INTERVIEW - Lean manufacturing principles, successful training programs and the involvement of management in daily continuous improvement are transforming Brazilian automotive supplier ZEN.

CASE STUDY – An entire restaurant chain going lean is not something you see every day. Coming all the way from China, Xibei's story of cultural change will inspire you to never forget the fundamentals of lean, from standardization to quality.