Down the right track

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – The author goes back to a train maintenance center she visited two years ago and finds an organization striving to learn continuously.

Words: Catherine Chabiron, lean coach and member of Institut Lean France

Two years ago, I visited Boris Evesque at his train maintenance center in Lyon. Knowing that the lean transformation had continued, I asked him if I could go back to see how time and continuous learning can change a lean team. (A quick reminder for you: the center works in three shifts on the cleaning, preventive maintenance and repairing of high-speed TGV trains in France).

So, what did the team change their mind about over the past two years?

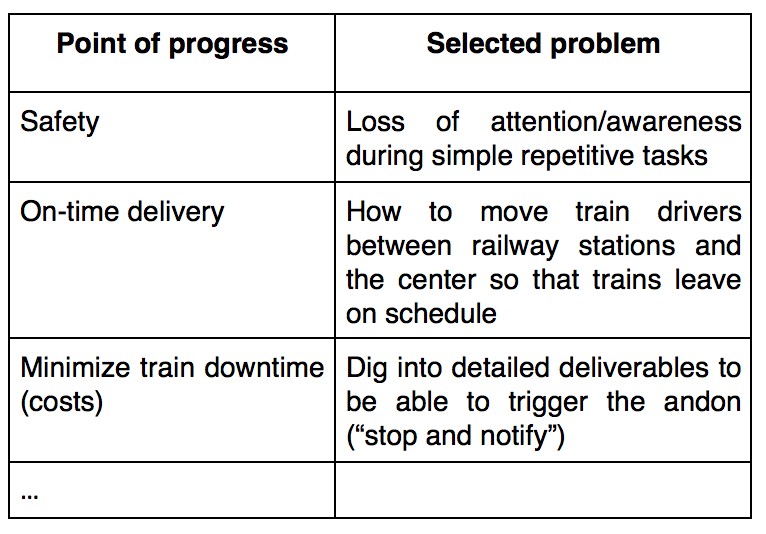

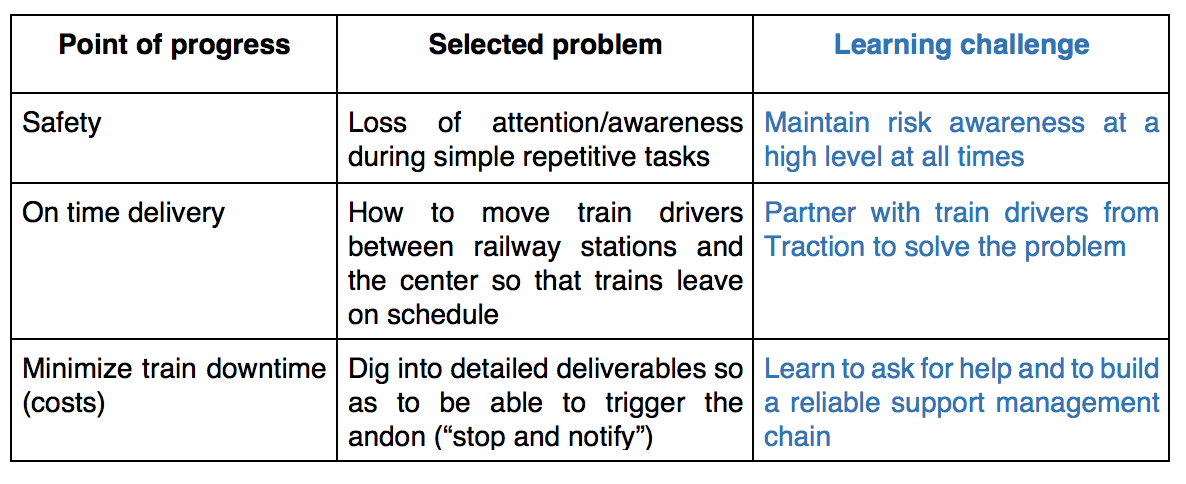

We start in Boris’s office, which doubles as his management Obeya. We first stop by his strategy board. The framework has not changed: points of progress and, for each of them, the ongoing tests and the next thing to learn. As to the points of progress, the team is still focusing on safety, on-time delivery of the trains (delivery), zero breakdowns impacting passengers (quality), train cleanliness (quality), improved train turnaround (costs) and on how to engage the teams (people). By the way, lean companies do not change their mind very often on their key challenges, to avoid jeopardizing their ability to continuously improve and learn. (Check any Toyota or Toyota supplier plant, and you will see a constant focus on environment, safety, quality, delivery and costs.)

What has changed in this SNCF center is that they have moved from long lists of actions for each topic to “Let’s decide what problem we want to work on” and to one-piece flow (“We can’t switch to the next issue until we crack the previous problem”). This means each area of progress shows one action and one action only, at any given time. This is a critical change: organizations typically have a million problems to solve and, unless they take the time to really think through what they want to focus on, they will be faced with many headaches, limited progress and poor learning.

As Boris and I face the board, we take a look at some of the problems the team selected:

Boris tells me: “The loss of awareness during simple repetitive tasks is the selected safety issue at the moment. In each team, we repeat many simple tasks in different and sometimes complex conditions, and this could lead over time to missing key steps. We need to maintain a constant control over tasks all the time.”

Boris quickly draws a graph on the white board showing awareness (on the Y axis) over time (on the X axis). If you do nothing, awareness will flare up if and when incidents are encountered and discussed. The challenge, however, is to maintain a high level of awareness over time, independently of incidents. The team had round tables first to think out ideas, then those ideas were displayed on walls for all to see and contribute to. They have now reached the stage where some of the ideas will be tested out by workgroups.

One such idea is that each collaborator will periodically take a 40-question digital quiz on safety (similar to the highway code test). In each session, questions are randomly chosen from a database built with real cases encountered at the gemba. At the end of the session, the team discusses the wrong answers.

This doesn’t mean that more specific safety issues are disregarded. It’s just that teams are asked to select a problem, dive deep into it and unearth its root causes. What is set here is the subject on which the learning has to occur.

The point on timely delivery is very similar: half of the late deliveries are due to the train drivers encountering difficulties in reaching the center on time, in order to move the trains (train drivers work for another entity, named Traction). The selected learning topic here is how the teams can learn to partner with their colleagues so as to better understand causes and work on them. In less lean organizations, the maintenance center would be happy to let go (“After all, this is not my responsibility.”) and this is how silos build up and collaboration plummets down. The trick is to find ways to simplify the work of their colleagues: help them better synchronize their routes in and out of the center, or simply help them out with taxis if they have no train to drive over to the center for maintenance but are needed to pick up another.

The discussion on the third problem is also very interesting. Minimizing train downtime has a huge impact on investment and costs: the center has managed over the years to double its train turnaround, thus offering the French railways the equivalent of 1 more available train per year, a global CAPEX savings of €210 million. Boris has developed metaphors to emphasize the message. “I tell them we do not want to be one of those highly specialised car repair workshops that target a maximized output, but rather a Formula 1 team at a Grand Prix aiming at the lowest possible time spent in the pit. The learning challenge here is to move from a classical scheduling of preventive maintenance to an approach managed by takt time and milestones that would enable the teams to see at all times whether or not they are running late – and call for help if they are. Jidoka is not so easy to master because, before one pulls the andon, many pre-requisites will have to guaranteed:

- Are we clear on the problems to which we want to apply Jidoka?

- Are we under time pressure (takt time)? If not, why bother asking for help, we can take the time to solve the problem on our own…

- Do we understand abnormal conditions?

- Do we trust our colleagues and team leader not to sneer at us when we ask for support?

- Will the team leader be available to rush out for support?

Focusing on one problem at a time is actually the best opportunity to learn something new.

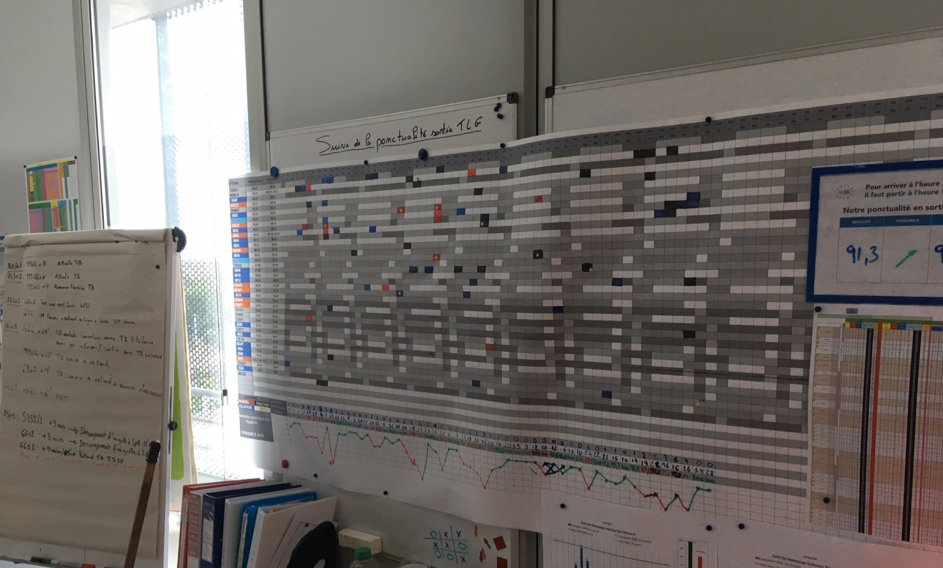

And, by the way, in each office or maintenance area we will visit after this initial stop in the Obeya, I can spot at least one of the selected points of progress. In Supervision, for example, they record on-time delivery for each train (point of progress #2) and plot the ascertained causes on an Ishikawa.

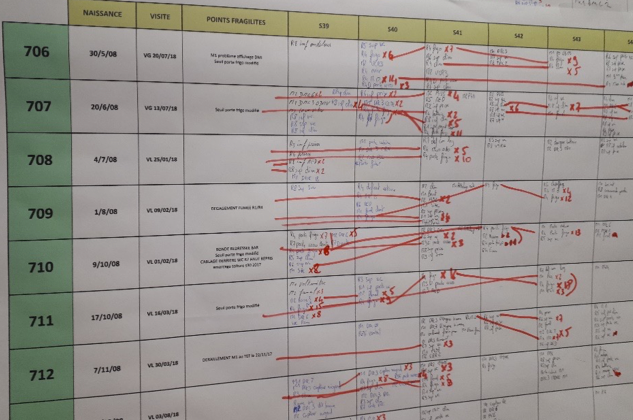

In maintenance, a full room is dedicated to breakdown analysis, where they highlight in red the recurrence of some of the incidents (point of progress #3).

VA-VE IS KEY

Working out the overall strategy of the center and its learning points are not the only instances in which Boris’s views have changed. As we start a discussion on how he plans to reduce the number of breakdowns impacting train users, Boris admits that the views of the team on the role of maintenance have drastically changed. He says: “When I took over this center, we just wanted to make the best job possible on maintenance. We started with kaizen and improving standards and all that, but still, the customer was far away. When you came two years ago, we were just starting to think how we could better interface with Engineering to tackle a couple of what we thought were design issues, but that’s all.” Actually, working on lean thinking and on customer satisfaction (by customer, I mean train users, not the next railway function in the process) led the team to think in terms of VA-VE (Value Analysis and Value Engineering). How could the product itself be improved, not just maintained or repaired? Working on this very idea, they have recently managed to convince the organization to permanently assign four engineers to the site to create a mixed team of such engineers and maintenance technicians to work on recurrent design issues. A very unique approach, as normally engineers and maintenance technicians keep to separate geographical locations.

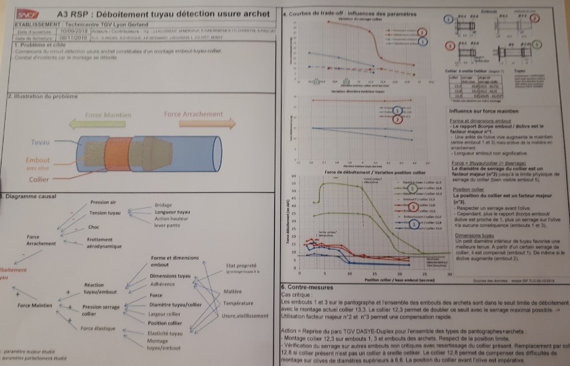

The result is already impressive. As we step into the new engineering office, I can immediately spot textbook A3s on the walls, where problems are efficiently and visually described with drawings, graphs, and points of cause, where causal models are defined after raising hypotheses and testing them out, and trade-off curves sketched so that countermeasures can be adequately selected.

One of the engineers is actually engaged in a conversation with the maintenance technicians to explain the assumptions he made and the confirmation he arrived at so that they can all agree on effective countermeasures. Boris chuckles. “This is actually the tricky part. It is all well and fine to conduct tests and build trade-off curves on two characteristics adversely impacting the performance, but now comes real life: how does he convince the guys who open up the machine daily that his proposed design change is the correct one?”.

I am still impressed by how quickly this recently-established team has managed to become so good at designing A3s and causal models. “We gave each of them a copy of Visible Knowledge for flawless design, the secret behind lean product development. They read it, we discuss it together and they try it… but we’re still learning our trade here,” Boris explains. One of the engineers admits he has not gone further than Chapter 3: “Beyond that, they discuss how to manage the whole process and this is not my role.” Boris argues that one has to understand all the ins and outs of a key activity such as managing knowledge, if only to understand the point of view of others.

We now move over to the “production” area, where maintenance and repairs take place. Now, did the maintenance team change their mind about something, too?

THE FORMULA 1 PIT IDEA IS BLOSSOMING

The huge maintenance center (as high as a cathedral and as long as, well, a railway station to accommodate for trains) has not really changed over time, but 5S and kaizen are at work here. This is just as clear to me as it was two years ago.

We go over to the bogies maintenance area, those 7-ton frames and wheelsets you see under the train cars. When you want to change or maintain the bogies, you disconnect and then lift the entire train in the air, roll away the bogies, replace them with other bogies, and pull the train down. Piece of cake, right? The last time I visited, the team had designed a fully-equipped trolley with everything that was needed for any work on the pantographs. They liked the idea so much that, as per SMED rules, they have now designed what we could call ready-to-maintain kits on dedicated trolleys to accommodate any type of preventive maintenance. Just as kitting is done to prepare all the necessary components for a given assembly, they have placed on trolleys all the tooling, cables, fluids, hoses that they will need, thus saving significant time (the technician no longer has to collect tools from the warehouse).

The idea of the Formula 1 pit seems to have blossomed here.

A little further along in our tour, Boris shows me another example of their work with SMED and tooling with a brake-checking trolley. To cut a long story short, they severely “kaizened” the trolley, fastened the air tank that was loose and regularly impeding operations, reduced unnecessarily long hoses and eventually saved between eight and sixteen hours in maintenance time per train on the brake checking process. But the story does not stop there: the trolley itself has to go for maintenance from time to time and the first time it did, the trolley supplier team diligently re-installed all the hoses that had been taken off, resetting the kit to its default design. This led the team to request a change in approach: maintenance is now done on site (the maintenance team comes over instead of having the trolley brought to them), thus reducing the trolley downtime, enabling discussions with the train technicians and further competence development on both sides.

DOJOS GALORE

Another point on which the maintenance team’s thinking has changed is training. General training continues both in training centers and mostly on the job, but as the teams introduced 5S and kaizen in their workstations or learned tricks and issues from breakdown or downtime analysis, they realized they needed to share what they had learned to prevent reoccurrence. Relying on training centers to teach the specifics proved too complex, so they had to think of something else. Two years ago, one dojo to teach train cleaning had barely been installed (it still exists), whereas today 26 dojos exist in Maintenance and one in Supervision. They only concentrate on watch points: for example, Supervision will train new hires on specific, tricky scenarios on train movements selected out of painful experiences. In the same way, the toilet cleaning dojo will help a trainee discover that air flushed through the piping to unplug a unit will also very efficiently shoot toilet paper (and more) on the ceiling if one does not remember to lower the cover.

Is everything perfect at the SNCF maintenance center? Of course not! There is a reason why they say lean is a never-ending journey, and Boris can indeed point to a lot of improvement tracks the team is currently busy with:

- In logistics, delivering everything when needed, in the required quantity and where it is needed remains a distant True North even if some progress has been recorded.

- Retaining and sharing knowledge efficiently everywhere and every day through job instructions has only just begun.

- Teamwork with subcontractors (for the cleaning of trains and for the maintenance of tools) is only now emerging.

- Scheduling is still an untouched land of opportunities.

Boris’s daily gemba walk sets the pace for the kaizen and problem-solving activities and his focus on the train user satisfaction have clearly put the entire organization on the path of learning.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

CASE STUDY – This automotive parts supplier based in southwest Spain is discovering the power of lean thinking applied to recruitment and Human Resources.

INTERVIEW – A VP at energy company E.ON shares his thoughts on the current energy crisis and discusses how lean is helping them to navigate it.

FEATURE – To boost the “adoptability” of Lean and sustain it over time, it’s necessary to develop institutions that support our improvement efforts without making processes more bureaucratic.

INTERVIEW – What is the secret to Toyota’s ability to engage people in continuous improvement? Tracey and Ernie Richardson look back at their time with the company and tell us.