Can healthcare learn from software firm Menlo Innovations?

FEATURE – Menlo Innovations has proved there is a different, more "joyful" way of running a software development company – could those same lessons be applied to the healthcare industry?

Words: Alice Lee, expert in lean healthcare, Senior Advisor to the Lean Enterprise Institute, and former VP of Business Transformation at Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts

After spending a good chunk of my career working in the IT and healthcare industries, I have come to the conclusion that software engineers and physicians are not that different. These folks are accustomed to being the "smartest kids in the class," people who from a very young age have been taught that they are the experts, the ones with all the answers.

Here's an example. I recently spoke to a surgeon who splits his time as a healthcare administrator. He told me that his favorite time of the day is when he is in the OR because that's when he is "in charge" and people don't question his decisions.

It is frightening to think this is the value system in place in some of our operating rooms. We have created a model, whereby nobody ever questions the expert, and I believe this is a key contributor to the poor performance and seemingly insurmountable problems plaguing the healthcare industry the world over.

The IT industry is remarkably similar. However, evidence is starting to appear that approaching work in a different way and writing better software in the process is possible. The best example of this, in my opinion, is Menlo Innovations, the Michigan-based software company.

Its CEO (and author of best-selling book Joy Inc), Richard Sheridan, spoke at the recent Lean Transformation Summit in New Orleans, sharing his belief in the link between joy and business results. [To read Planet Lean's interview with Richard Sheridan, click here]

As a former IT leader who has created her share of pain for end-users (I didn't know about lean back then), I see Sheridan and Menlo being a far cry from your typical IT professional and company.

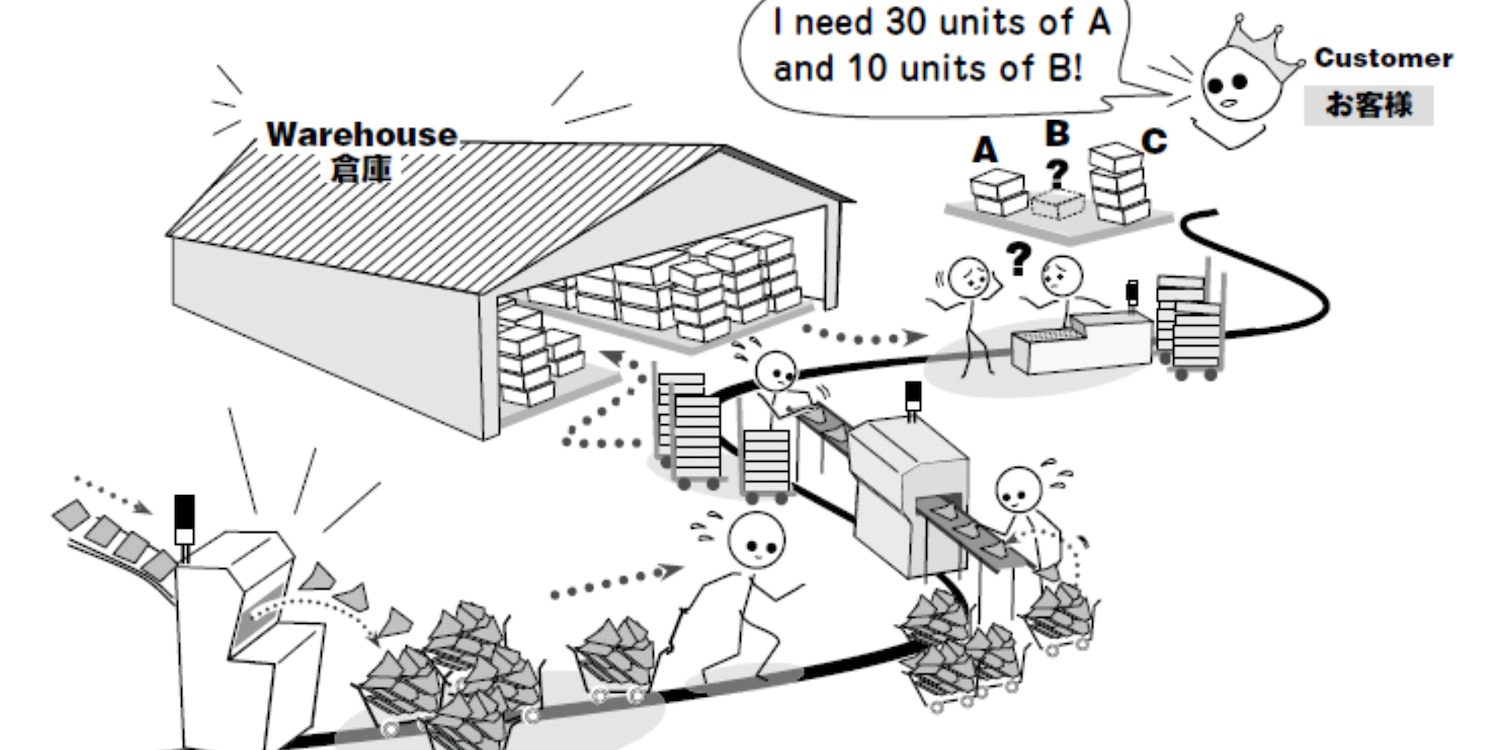

The usual attitude of software companies is, "we design and build the product and you use it." Software engineers are commonly seen (and see themselves) as the experts who create smart software for stupid customers.

A few years ago, Sheridan had an epiphany: we may be the experts, but we are making products people don't like and can't use. In hospitals, our beleaguered physicians, nurses and other clinical professionals experience this every time they are handed software tools that are not really designed for them, but to meet business needs (like capturing billing information). These tools can actually make their days even longer and more stressful as they are often overlaid onto fragile work that has yet to be thoughtfully designed and integrated around the care of their patients.

Both the healthcare and software industries operate mostly in chaos and firefighting, with very little value generated. In fact, the perception there is that firefighting is the process! Problem is, when we firefight long enough bad things usually happen: we hurt people or, in the case of software companies, we create bugs (resulting in systems crashing) or at the very best, workarounds for their end-users.

CAN WE APPLY JOY TO HEALTHCARE?

Sometimes I wonder if we even remember why we chose to do what we do. As healthcare professionals, what was our purpose for signing up to a life spent with people who are suffering? Normally, it is a desire to help others and make a difference in people's lives.

Yet, the things happening around us every day, starting with the structure of our organizations, make it impossible for us to introduce positive change and really have an impact. We are just too busy firefighting.

Solving problems, getting results more easily and essentially producing more value more often makes us happy and brings us closer to our original purpose. To put it in Menlo terms, it brings us joy.

One of the things that strike me the most about Menlo Innovations is their mission statement: "to end human suffering as it relates to software." To end human suffering! Shouldn't we in healthcare talk about this more than a software organization? And wouldn't ending human suffering bring great joy to those of us caring for patients?

Like Sheridan, I believe there is an alternative to the joyless workplace that many of us are experiencing. Our misery on the workplace is tied to the sub-par processes we are trapped in and, truth be told, much of it is in our control. Unfortunately we often don't know that; even more often, our leaders accept the status quo as the norm.

That's why leadership is so critical. Healthcare is quite hierarchical and is characterized by a culture in which we look at the boss for answers. Fatally, this slows down organizational problem solving and the development of capabilities.

A WRONG APPROACH TO LEAN?

One of the things I worry about as I look at lean applied to the healthcare industry is the prevailing copy-and-paste model. I have been working with lean in healthcare for over 10 years, and I must say it was great to be part of the group of early adopters mainly because we couldn't copy anyone. We were forced to think for ourselves and try and learn in the process.

Soon after we began, however, others in the industry started to adopt the same rapid improvements approach some were using, assuming it would work for them as well. These days it is the boards everybody is setting up in their work units, with little to no attention paid to the individual circumstances of each organization. The idea seems to be that to be lean all you need to do is organize the huddles, implement a daily management system, or use tiered boards.

To me this is just copying what we think is going to work, as opposed to trying to understand what our problems are, given our own situation and circumstances. That's why, in my opinion, it is the focus on the "situational approach" that makes the Lean Global Network's Lean Transformation Model so powerful.

Industrial tourism is not good enough. Copying somebody else's artifacts is not good enough. Sure, it will help and get you some results because healthcare is in complete chaos, but they will not bring lasting change to the way people think and behave. To achieve that, a more germane undertaking is required.

Perhaps more than in any other sectors, change in healthcare happens situationally - doctor by doctor, personal transformation by personal transformation. When I take physicians through sessions on how to apply their lean learning, they keep asking what the best practice is. I point out that best practice is nothing but the best way we know today, not the end point, and this is revelatory for them. Being told that, while you might adopt best practice, you need to go further and keep learning, experimenting and improving is somehow a difficult concept for them to grasp, at least initially.

The funny thing is that, despite being a science-based industry, healthcare tends not to use the scientific approach to understanding customer behavior and needs. Physicians are used to studying new things to stay up to speed with the most recent research, and regularly use PDCA thinking for the clinical problems they face and to treat patients. Unfortunately, they aren't trained to use it to design their processes.

I soon realized (and what a revelation that was!) that this has to be at the core of your capability building, because doctors are not naturally going to go with this thinking just because "they are scientists."

A FEW LESSONS FROM MENLO

One of the most impactful features of the "Menlo model" is the pairing of associates for all work activities, including programming.

This system contributes to the natural sharing of ideas and the avoidance of bias and assumptions as one checks the other in a pair. It also pushes everyone's thinking further as people work closely with others on a rotating basis. As a result, there are no "towers of knowledge," those people in our organizations who seem to know everything and that we end up relying upon completely.

If teams at Menlo look like sports teams with associates shoulder to shoulder, those in healthcare reflect the traditional organizational chart. Hierarchy is still the name of the game in our hospitals and other healthcare organizations. Where it is natural and collegial at Menlo to learn together and provoke each other, the same questioning of another person can be considered an adversarial stance in the healthcare world.

Another key lesson we can draw from Menlo is their use of anthropologists (High-Tech Anthropologists in Menlonian) to study how customers interact and behave in the field. This will inform the design and direction of the products to be developed, and ensure they will delight their users long before a single finger has been laid on the keyboard.

What was learned during observation on the field is reflected in "persona maps," a practical tool that helps to understand for whom the company is designing a specific solution while keeping the designers laser-focused on their customer. It is also a way to create a product that will surely delight end users.

At the 2015 Lean Transformation Summit in New Orleans, the Menlo team held a session in which attendees were asked to create "persona maps" once given a certain scenario. I observed the healthcare professionals at my table, and you could see this seemingly simple request cause consternation and debate.

When we can't figure out who our end users are and for whom we are designing a process, we will create a watered down solution for everybody. Of course, that never works and no one is happy.

HOW DO WE GET THERE?

I am not advocating that we copy Menlo. In fact, that is the trend I am warning lean practitioners against. People who visit the company often come out with the idea to start pairing people, as if that was the real reason behind Menlo's success. Truth is, there is no replicating somebody else's model (it is not possible with Toyota, and it is not possible with Menlo).

There is little doubt, however, that a more Menlo-like approach would greatly benefit healthcare organizations. There is nothing wrong with visiting exemplars to trigger thinking and provoke action that makes sense for one's own organization. You may even have a solution inspired and similar to one you saw. What is important is to understand your organization's challenge before solving it, and to determine what joy really means to you and how you are going to achieve it.

In academia and healthcare, we tend to create deep silos of knowledge that blindly operate in hierarchical environments where the expert is king. At Menlo, diversity is built into the teams and all people are equal learners and collaborators. (Even the CEO sits with everybody else, with his team changing his workstation location weekly.)

If healthcare is to improve, we must:

- understand how to unlock every person's, team's and leader's potential;

- be given the opportunity to think aloud in a safe environment and to enjoy the free flow of ideas around us, so that we can learn continuously;

- learn to iterate towards a solution instead of jumping to one;

- understand and accept that failing when testing ideas is a valuable learning component and not an end point;

- enable collaboration and create an environment free of judgment, in order to let great ideas emerge and to allow people to be creative.

Traditionally, healthcare honors analytics more than creativity. However, the two must work together when designing processes and products that work for our customers. When I support the lean thinking development of physicians, I make sure they understand that creativity means learning to solve complex problems together with their patients in mind.

Undoubtedly, this requires the traditional idea of expertise to be revisited, so that we can allow for more collaborative discussions, prevent wholesale copying of other people's best practice, and stop forcing knowledge to sit in silos. [This is one of the challenges lean thinking faces, not just in healthcare, as Professor Dan Jones explains in this article.]

Finally, we need to inject empathy in the design and delivery of care services, which is achieved by thinking about our own and our family's failed healthcare experiences. More often than not, patients are seen as diseases and diagnoses rather than people (hearing them referred to as drug seekers, frequent fliers, walkie-talkies is sadly common).

Only empathy will allow us to create a healthcare system that works for all people - from patients to doctors - in which leaders unleash the collective genius of their teams. I remain hopeful.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – Lean thinking is increasingly applied end to end, reaching virtually every area and function of the enterprise, and yet in many companies IT is still left out of the lean transformation. Isn't this dangerous in a world that is going more and more digital?

FEATURE – The release of Christoph Roser’s new book All About Pull inspires John Shook to discuss the origins and true meaning of “pull” and why it is incorrect to blame JIT for the shortcomings of global supply chains.

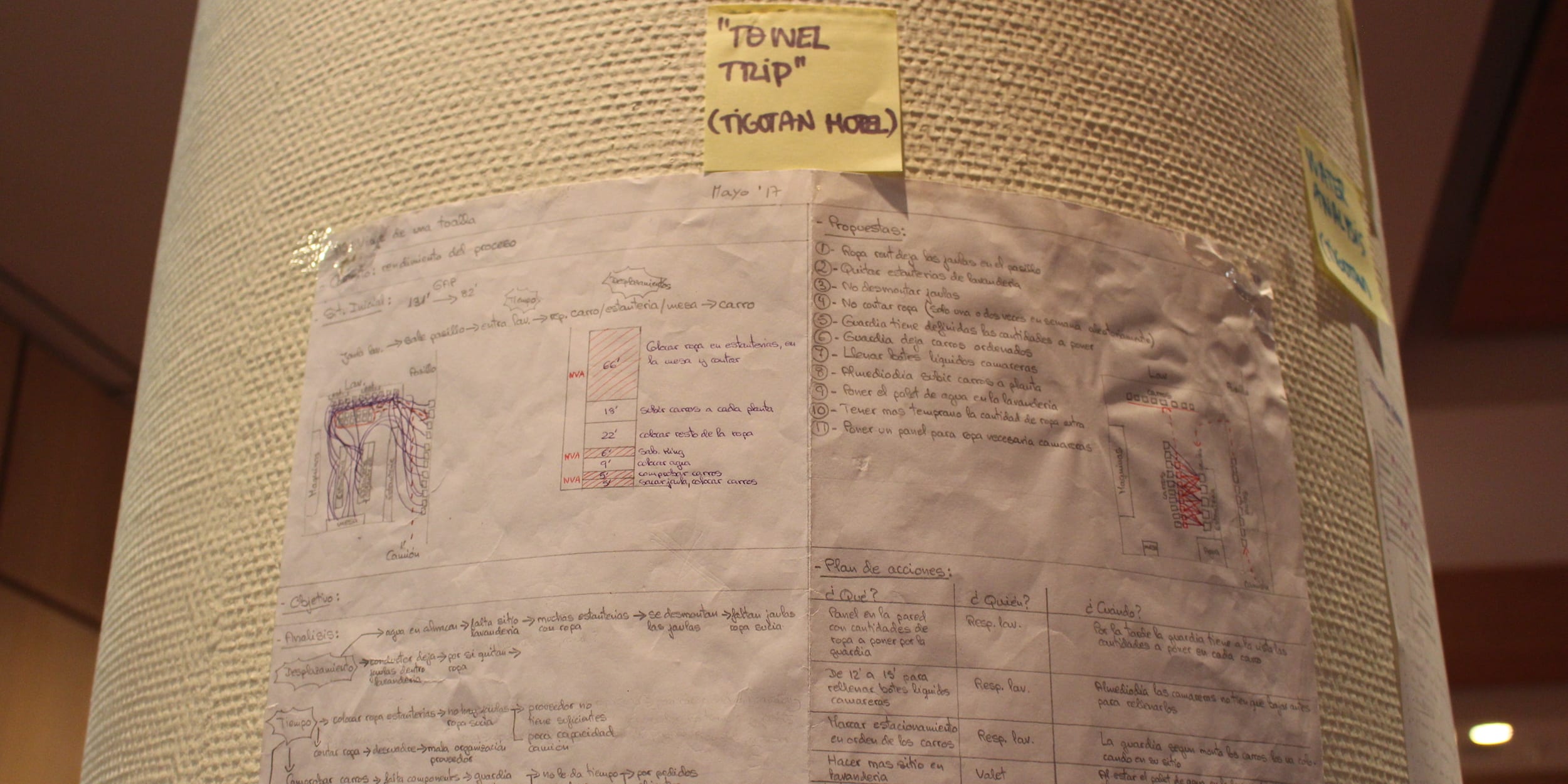

VIDEO – The director of a hotel in Tenerife explains the first steps the team is taking to develop a lean daily management system, and how this connects to the organization's hoshin.

FEATURE – Designing beautiful work helps design beautiful clothes. Here’s the story of how women’s clothing brand Eileen Fisher found in lean a way to support its environmental sustainability strategy.