Adopting lean principles to speed up blood donation

FEATURE – In the second article of our lean healthcare series by the front-line staff of Siena University Hospital, we learn how the principles of pull and flow have transformed the blood donating process.

Words: Morena Venturini, Manager of the Professional Operating Unit of Laboratory Diagnostics, and Francesca Marchi, Technician, Lean Office AOU Senese

In 2015, our facilities received 4,415 blood donations – welcoming, on average, 33 donors per day – and produced around 14,533 units of blood and blood products. Unfortunately, due to the faulty process we had in place, people had to endure very long waits to donate blood.

As the complaints kept pouring in, the immunohaematology and tranfusion medicine team decided to turn to lean thinking, which was already present (and thriving) in many other parts of our organization, in a bid to shorten waiting times and hopefully offer a better service to our donors.

In January 2016, we initiated a seven-month project called "If blood doesn't flow," with the help of our Lean Office.

We started by assessing our performance, measuring lead-time and donor flow for two weeks. We found that, expectedly, the average length-of-stay (LT) varied depending on the type of donor we received: donations on appointment took an average of 81 minutes to complete, while drop-in donors tended to wait 117 minutes on average (with a peak of 270 minutes). No wonder they were complaining!

The analysis of the data revealed that the length-of-stay markedly increased in the first few hours of the day and towards the end of the week (the times when most donors showed up at our doors).

Many of the people working in our ward stressed that the solution to this problem would be to increase the number of donating chairs, but when we looked at their occupancy rate we found that it was a mere 39.8%. The problem had to be elsewhere. So we decided to map the donors' flow using value stream mapping.

It became apparent that the bottleneck was right before the medical examination: after a preliminary blood sample was taken, donors were asked to go back to the waiting room until the clinic was able to welcome them back. Our work appeared fragmented, chaotic and full of unnecessary interruptions.

The team aimed to immediately reduce the waiting time for planned donations, to ensure the appointment time donors were given corresponded to the actual time of donation. We expected this (together with a campaign we ran to increase awareness) to incentivize more people to choose to book an appointment rather than drop in to donate, thus reducing the variability we experienced.

With a final goal of reducing the waiting time by at least 20%, we introduced a number of improvements to the way we organize the donor's path. Appointments are now scheduled avoiding any sort of overlapping or interference with other patients' paths (like transplants, for instance), and we use a visual board with a kanban card for each donor to regulate their flow.

The change that did most to improve the way we manage flow, however, was the introduction of a pull system: the donor is called into the blood exam room when the previous donor goes in to see the doctor, so that we only have one donor flowing along the path at any given time, without interruption or ever going back to the waiting room. Each step now pulls the following one, and the bottleneck has disappeared.

The reorganization of donors' flow, which was supported by a change in the layout of the admissions office and the waiting room, brought us great results (with no additional resources invested): each year, our donors don't have to wait as much as they used to and walk a staggering 372 kilometers less than before. Our people have also told us how much easier their work has become, and how stress has decreased in the ward. That's what we call a win-win!

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE - What do Toyota and Procter&Gamble have in common? A passion for developing people, a focus on customer satisfaction, and... enviable results that are sustained over time.

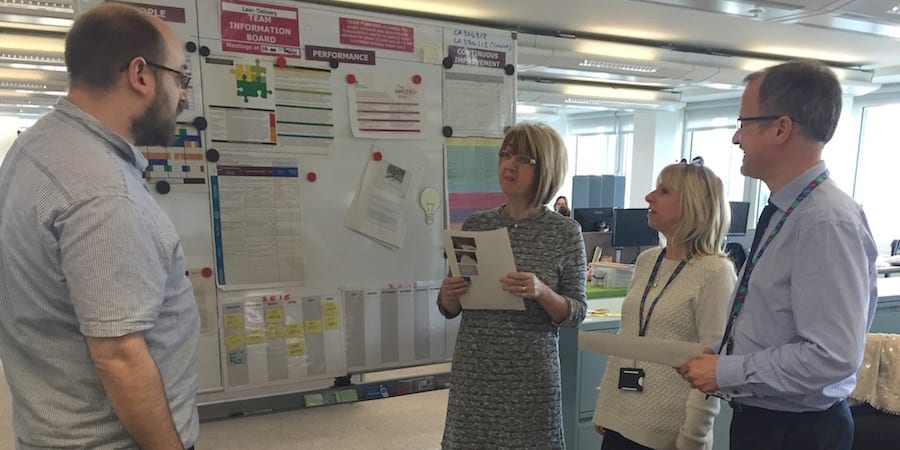

PROFILE – Lean leaders are often tempted to jump in and fix the problems they see. Julie McGrory is successfully transforming the culture of a large and traditional government organization by learning to take a step back and letting people take the lead.

THE TOOLS CORNER – In this new series, we go back to basics, offering a guide on how to implement some of the most important lean tools and explaining why they are so clever. First up, Kanban.

VIDEO INTERVIEW - Planet Lean speaks with Jeff Sutherland, one of the inventors of scrum software development, about the evolution of this Agile framework and its relationship with lean.