Lean-powered decision making

FEATURE – As lean thinkers, our focus is on problem-solving. The author explains why effectively solving problems depends on our ability to make the right decisions and suggests the lean community plays closer attention to this.

Words: Flávio Battaglia

Every day, each of us must make decisions. Countless decisions, in fact – ranging from what we are going to have for breakfast to how we should engage with people around us, from what time we should leave to go to the office to how we are going to spend our free time. Our daily lives are continuously, significantly, and directly influenced by the choices we make, which is why how we make decisions has always been a topic of great interest to neuroscientists, psychologists, sociologists, etc.

In the business world, too, decisions are expected of people at all levels of an organization, and it is the combination of those decisions that determines whether a company is ultimately successful. Do people at the front line flag up problems or do they hide them? Do managers strive to improve the system, or do they blame people instead? Do senior execs think long-term when coming up with their strategy or do they choose to just focus on making money now?

In the lean world, we often say that people should be given the tools and autonomy they need to make decisions and, therefore, solve problems, but I believe the focus of our attention has traditionally been problem-solving to the detriment of decision-making. Yet, without decision-making one can’t be expected to solve problems.

So, why not pay attention to how we make our decisions and see how the lean way of thinking and acting can help us ensure these are the best they can be?

FIVE STAGES OF DECISION-MAKING

As mentioned above, theories on decision-making abound. It is mostly described as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a course of action among several possible options (could be either rational or irrational). According to Herbert Alexander Simon, decision-making is a reasoning process based on assumptions of values, preferences and beliefs of the decision maker. Every decision-making process produces a final choice, which may or may not prompt action.

If we try to look at this cognitive process from a lean perspective and break it into smaller steps, we can say there are five main stages in the decision-making process:

- Perception – how good and trained we are to see the reality around us and recognize certain stimuli as problems requiring our attention.

- Intention – based on what we perceive, how willing and determined we are to act and do something about a problem.

- Evaluation – how I am going to assess the risk and benefit of acting on a certain problem. Is it worth acting on it at this stage? Do I have what I need to succeed? At this stage, we are trying to weigh up hypotheses.

- Action – based on our evaluation, we decide to act (or not) and use the tools at our disposal (in the case of lean, things like daily management, huddles, kaizen or hoshin) to bring our vision to fruition.

- Reflection – how good we are at extrapolating lessons from our experience. Did our intervention pay off? What did we learn from it? What’s the impact it had on the system?

LEAN AND DECISION MAKING

The five elements highlighted above describe how decisions are made, the thought process that causes us to see reality one way or the other, to choose a certain course of action, to draw conclusions from something that happens to us. Because lean is so tightly connected with the way we think, I believe that it can help us to ensure that our decisions are the right ones.

Applied to these five elements, in fact, lean can turn decision-making into a powerful driver of a transformation. Its scientific approach provides us with a structured way to make decisions, even when these happen almost subconsciously (which is why it’s so important to make lean second nature, the way people see the world around them).

Lean tools and principles make the decision-making process as effective as it can be. How?

When it comes to perception, with lean we learn to see. This means developing our ability to see problems, to separate value-added work from waste. Because we get our information directly from the gemba – rather than a report or a presentation – we have a much more accurate understanding of the reality around us, of the problems we experience, on the decisions we are called to make. (This is where it becomes clear that decision-making is a much wider concept than problem-solving – if our perception is off and we focus on the wrong problem, we can be the best problem solvers in the world but that won’t mean much).

As far as intention goes, as lean thinkers we are driven to make daily improvements to provide more value to our customers, serve the best food we can in a restaurant, offer patients the best possible care. This passion for improvement comes from two sources: the motivation I receive and the knowledge I am given. Together, these two elements empower me, give me the will – and the means – to act. This way, each problem I observe becomes a trigger that awakens my intention to “do something about it”.

It is one thing to have the right intention, but what about evaluating the problem and the situation around it to understand whether my intervention has the potential to succeed? It is at this stage that we decide to act or not. After all, tackling a problem when we don’t have the knowledge or the support that we need is wasteful. This makes the evaluation phase critical. Lean can help us assess the situation, by encouraging us to ask questions such as, “Do I have the support I need from leadership?” “Are my people with me?” “Is this the right time to take this on?” “Do I have the tools I need to have an impact on the situation?” “Is it worth focusing on this problem or should it be something else?” Developing our evaluating capabilities is just important as honing our perception and problem-solving skills.

If we do decide to act, lean provides us with a wide array of tools, techniques and behaviors that can help us attack a problem – from its definition all the way to its resolution. The “action” phase is the problem-solving we typically talk about in the lean community. A3 thinking, kaizen, engaging with cross-functional teams, gemba walks, 5 whys – one could say that everything lean teaches us is ultimately meant to make the problem-solving process smoother and more effective.

Finally, we can’t forget the reflection phase. Doing hansei is also a decision. Too many neglect this critical activity, only to find how big a hindrance this is to our ability to transform organizations. Reflecting on the decisions we have made, on the problems we have solved and how we have gone about it, and on the impact that this has had on the overall system means that we will be better equipped to solve future problems of a similar nature. The more problems we solve, and the more we learn from them, the better we will be at solving future problems – it’s the virtuous cycle of lean. Without learning and capturing knowledge, there is only so much progress we can make (not sure if I got the meaning of this final sentence).

TWO EXAMPLES

Let’s try to imagine two real-life scenarios to bring these ideas to life. In both cases, a patient in a hospital is given the wrong medication. Here’s how a non-lean decision-making process and a lean decision-making process would unfold.

In the first case, a middle manager learns about the incident. He is an old-fashioned guy, working in an old-fashioned environment. As he looks at what happened – indeed, giving the wrong medication is a very common occurrence in hospitals – he immediately shrugs the problem off by saying, “We have so many of these. No one ever died. We always find out in time.” This flawed perception of reality (which leads the manager to believe this is not even an issue) results in a complete lack of intention to do anything about it. The evaluation of the problem convinces the manager that the best course of action is to ensure that news of the incidence doesn’t spread. “We will do something about it next time. We have so much to do already,” he thinks. No problem has been tackled, and there is therefore no learning that can be drawn from the experience. Fast forward a few months, another patient is given the wrong medication. This time, however, she develops a rash all over her body and the hospital ends up with a lawsuit on its hands.

In the second case, the manager is a lean thinker. Someone tells her about the medication error, which she immediately sees as a problem that the whole team needs to look into. The manager knows this is common problem in hospitals. She had in fact worried that this might happen while visiting the gemba recently – where she remembers wondering how the pharmacists managed to tell medication apart when so many of them came in such similar containers. Her experience studying the work at the gemba has changed her perception and immediately alerts her that the medication error is a huge problem. As a lean thinker, her first instinct – or intention – is to solve it. For her evaluation, she goes to gemba and talks to as many people as she can, really trying to grasp the situation and understand whether an intervention can have the desired result. Once she determines that this is in fact the case, she decides to act. She forms a small team to analyze the problem in depth and uses A3 thinking to solve the issue once and for all through a simple, but clever system of colored tags and poka-yoke. As the team gathers to reflect on their learning, the success of their kaizen inspires them to share their experience with the rest of the hospital so that other areas can also avoid medication errors. A year later, the hospital records zero instances of medication error for six months in a row (and counting).

WHY NOT SIMPLY PROBLEM SOLVING?

Until now, we have discussed how applying lean to the five dimensions of decision-making makes great sense. But the same positive outcomes can be seen if we look at this the other way around: decision-making gives us a much more complete view of our lean transformations than just problem-solving. It forces us to ask ourselves questions that would otherwise remain unanswered – what problems do we pick? Why? Based on what indicators? Why do I decide to go ahead and tackle this problem?

Looking at the five key elements of decision-making might just make us better at lean, because it can add a new dimension to our discussions and give us a new way to look at the challenges before us. To those of you who are on a lean journey and feel sometimes stuck, this perspective can help you see things in a different way, find new doors to unlock. Decision-making lies behind all the dimensions of a lean transformation, which is why it is so important we look at it and better connect it to our lean transformation efforts.

As we study lean transformations, our focus until now has been almost exclusively on problem solving. While this is of course fundamental (it lies at the heart of lean), problem-solving without solid decision-making goes nowhere. I think we are missing an opportunity by ignoring the role of decision-making in our lean journeys. If we believe that decision-making constantly comes into play in our daily lives, why are we not discussing it more? Why don’t we treat it as the transformation driver it is?

THE AUTHOR

Read more

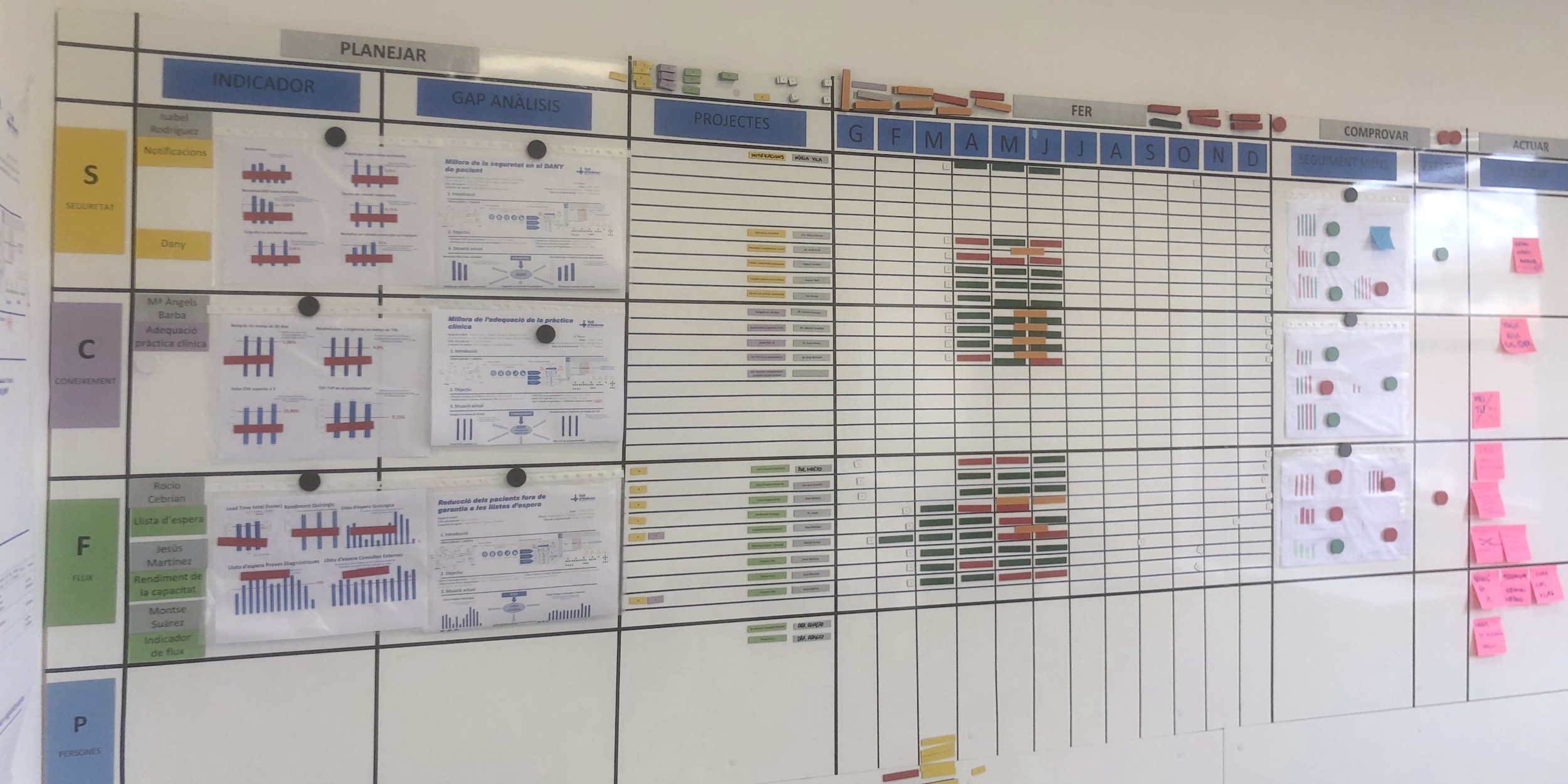

CASE STUDY – Catalonia’s largest hospital is undergoing a successful transformation – supported by pioneering hoshin experiments – that has already turned it into a poster child for lean healthcare in the region.

FEATURE – An obeya room can be the cornerstone of a lean transformation, but developing a successful visual management environment is easier said than done. Nike’s Technology department shares a few tips.

CASE STUDY - A Turkish shipyard and engineering company has found that lean principles and practice are the only way to deliver unique, large construction projects efficiently and successfully.

LEAN THINKING WOMEN – We speak with women lean leaders about the link between gender equity and the creation of value as well as the value of diversity to the global lean community.