Jim Womack on asking questions rather than providing answers

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN – As a first instinct, most of us tend to provide answers and solutions rather than ask questions. Jim Womack provides advice on how to fight this behavior and become a coach.

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

Bob, as I will call him, recently asked me to take a walk through his organization. He is the COO of a massive enterprise with 12,000 employees and wondered how it could be more successful in achieving its mission of cost-effectively providing a specific sort of value to a vast group of customers.

We started in operations, the area of the business where Bob had begun his long career, and I was amazed at his grasp of details about every activity. Everywhere we went he offered suggestions to practically every employee on how their work might be performed better, with the implication that they had best act on his advice as soon as possible. He was, in short, the Answer Man.

As we walked from area to area and department to department, his ability to answer every question never wavered. Except there were no questions from the employees. Instead, everyone listened quietly to the boss answering his own questions. But how could he possibly know the right answers to the right questions in areas where he had never worked or had not worked recently? I could see in their faces that they knew that Bob too would soon pass and they could get back to doing what they already planned to do.

It was then that I began to feel a bit sorry for Bob. He was carrying a very heavy burden indeed. His vision of himself as an effective leader was that he could somehow give everyone the answer they needed and then exhort them to give his answer a try, even when his own knowledge was incomplete at best. And it was having no effect. All the charts we later reviewed in the conference room were running sideways. There was no sustainable improvement.

At the end of our walk he inquired about a "lean program", which he had concluded would be the answer to many of the organizations bigger problems. And he asked about the best consultant to provide it. This question seemed to be only one for which he did not have a ready answer.

I've had many walks of this sort and met a lot of Answer Men in my career. Indeed, I look at one every morning in the mirror because my natural instinct is to quickly provide an answer even before the question is fully stated. I hope I am now a recovering Answer Man but it has been and continues to be a struggle.

What helped me get my head to a different place was to force myself to observe the effects of my giving answers on those I was trying to help. (For a lovely essay on why the simple notion of "helping" is fraught with misunderstanding see Edgar Schein, Helping: How to Offer, Give and Receive Help.)

In the end my answers were often wrong because I had not deeply examined the gemba. In trying to help I was simply suggesting that they try a tool or method I had seen work elsewhere in the past. But even if my answers were right, I had taken on the responsibility for the problem and the pursuit of my answer was unlikely to be sustained. I gradually learned that asking big questions about organizational purpose and then finding a way for good people with good training to search for their own answers and then to experiment with ways to solve the problems their answers posed was the only way to help.

When I walk now, I am often asked to provide a second opinion on the suggestions and programs of consultants who have tried to help the organization in the past. From this experience I have learned that not being the Answer Man is a particular challenge for consultants, whether they are internal to an organization (in some sort of continuous improvement or operational excellence role) or external resources. The widely held expectation for the consultant is that she or he already has the answer to the line employees' problems. It is the employees' job to act on this answer, often with more answers from the consultant about how to do this.

This highlights the big distinction, as I've come to see it, between consulting and coaching. The consultant may, of course, have the "right" answer at the outset, based on long experience with similar problems in other organizations. (This may not be the case, as I noted earlier, if there is no deep knowledge of the specific gemba – leading to the common problem of pattern recognition without careful investigation producing a false diagnosis and prescription.) However, even if the consultant has the "right" answer it is probably wrong in a more profound way.

The consultant's real job is to be a coach, helping the employees of the organization learn how to ask the right questions and then how to find the right answers for those question through deep enquiry. In short, the objective is to build capability in line employees through cycles of coaching about how to enquire about problems, investigate root causes, conduct PDCA cycles with countermeasures, and confirm countermeasures. (A countermeasure confirmed through experiments is the only "answer" that counts and an organization able to sustain improvement must have line managers with this skill.) So the deeper objective of the coach is to build question-asking and problem-solving capability in all of the organization's employees so that neither the consultant nor the coach is needed.

At the end of my walk with the Answer Man, after he asked what he should do, I went through the logic I have just described. I explained that his highly developed habit of giving answers was actually the problem. He didn't need a "lean program" but rather needed to transition from uber-consultant for the whole organization to a coach for his direct reports so they could coach their direct reports. (He also needed to create an effective hoshin planning process with a daily management system to provide stability and sustain gains.) He could then direct his very considerable energy to this different objective and achieve different and better results. This wasn't the answer the Answer Man was looking for and I haven't heard back from him. I doubt that I will.

This leaves me with only you to talk to and to hope that when you look in the mirror in the morning, as I try to do every day, you acknowledge your natural inclination to give answers and vow to be the Question Man and an inspiring coach instead.

A final note before I go: My wife has me pretty much convinced that being the Answer Man is usually a Y chromosome thing. I wish I didn't have to say that. But...I do. So some readers, although I'm not saying which ones, will need to stare harder into that mirror and make a special effort to become recovering Answer Men. I wish you the best with your personal transformation as I continue to work on mine.

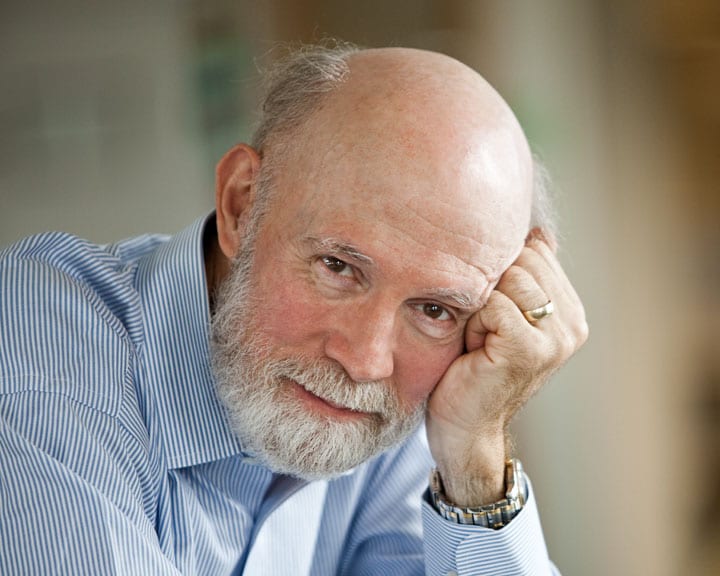

THE AUTHOR

Management expert James P. Womack, is the founder and senior advisor to the Lean Enterprise Institute. The intellectual basis for the Cambridge, MA-based Institute is described in a series of books and articles co-authored by Jim himself and Daniel Jones over the past 25 years. During the period 1975-1991, he was a full-time research scientist at MIT directing a series of comparative studies of world manufacturing practices. As research director of MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program, Jim led the research team that coined the term “lean production” to describe Toyota’s business system. He served as LEI’s chairman and CEO from 1997 until 2010 when he was succeeded by John Shook.

Read more

FEATURE – Is the traditional teaching model used in our schools obsolete? A high school in Italy has been experimenting with lean thinking and Scrum applied to students’ learning, and the results have been enlightening.

FEATURE - The author addresses the ongoing debate on rewards and recognition, explaining how an optimal relationship between team members, team leaders and group leaders will influence motivation.

FEATURE – In the face of uncertainty, when it’s hard to see the road ahead, we can still make things better day after day by embracing kaizen – until we are out of the woods.

FEATURE – We start the new year with a reminder to put customers first, always. It is they who make our business and keep our lean initiatives true, says the author.