Better thinking for better lean thinking

FEATURE – We tend to describe lean as a holistic approach to a transformation, but we won’t be able to truly embrace it until everyone starts to see the organization as a system.

Words: Bjarne Berg Wig, lean author and founder of LOS Norge, with Eivind Reke, Organisational Secretary of LOS Norge

Over the course of our careers, we have witnessed countless quality and lean initiatives here in Norway. What struck us is that those that are led by CEOs, who appreciate their companies as systems, seem to have a higher chance of succeeding. This leads us to believe that we should try and get more lean practitioners to practice system thinking.

In this article, Michael Ballé and Daryl Powell point out that “lean is a set of principles to create the conditions to think more deeply and learn by constantly trying to improve things and seek a better way, small step by small step.” For the lean community, this also means learning to think more deeply about our own thinking. We believe that Deming’s system of profound knowledge gives us a framework to do just that.

So, how can we create a world of systems thinkers?

Big and small problems, both at work and in our lives, require an appreciation of the system our problems are part of – in other words, the system that creates them. Trying to deal with the symptoms of a problem, rather than its root cases, suits our habitual thinking and doesn’t require much effort. Sadly, it also means that we will be dealing with that same problem over and over again, much like the “yo-yo dieter” throws him or herself to every new trend to lose a bit of weight, only to put it back on after a while. Getting to understand and recognizing this human dynamic is the first step towards becoming better lean thinkers.

COMPLEX, NOT COMPLICATED

As aspiring system thinkers, the first obstacle we face is the idea, or mental model, that system thinking is complicated. However, we must not confuse complex with complicated. The practice of systems thinking is the relation between our understanding of systems and how we think of systems. In other words, systems thinking is about creating awareness of our own thinking or – in more scientific terms – meta cognition. That is, to think about how we think. To learn how our brain interprets what it sees, feels and hears, and to better understand our own mental models. Let´s take a closer look at this relation: what are systems and how do we think about them?

According to Deming, a system is a network of interdependent components that work together to try to accomplish the aim of the system. Anything from our natural world to a manufacturing company can be, in Deming’s words, appreciated as a system. Many of the lean tools are in fact learning tools that support system thinking. Kanban, for example, gives us an access point to better understanding how our internal delivery system is connected (or not) to real demand. In the same way, Andon gives us an opportunity to study our quality or delivery problems at the source of discovery and the Ishikawa diagram or 5-why method help us trace the source(s) of a problem back through the system to its origin. The complexity of systems is real and is impossible to fully grasp. However, if we adopt a systems perspective, we can at least develop a better appreciation of how some changes can affect the system in completely unintended ways. For example, a change in how our sales department communicates its forecasts to production planning can have a big impact on how well we manage to balance production.

Developing an appreciation for a system is not something new or unique to lean. Farmers have studied weather phenomena for generations to know when to plough, sow and harvest. They observe the sky, the sun, the birds in the trees, the direction of the clouds, which are all signals from a system. Our families, too, are systems – made of many actors and factors, like parents, children, grandparents, how and where we live, the school we go to, our upbringing, and so on. Deming taught us to see our organization as a full system, which includes ourselves and our role in it, to understand how the system behaves statistically (common cause and special cause variation), to understand human psychology and to develop our theory of knowledge. A better understanding of the system and of variation will help us to understand the underlying causes of problems, and see the most important factors that are almost always hidden. Psychology can help us appreciate why we act the way we do within a system, and developing our theory of knowledge can help us to see the underlying assumptions that influence our own thinking.

AWARE OF HOW WE THINK

When Deming introduced his system of profound knowledge (SoPK) in the 1980s, he pointed out that a key element of it is understanding psychology. He also purposely linked together four elements: psychology, understanding variation, theory of knowledge, and appreciation of a system. Each of the elements is individually crucial, but also has a special synergy with the other elements when one understands them as a part of the whole SoPK approach. However, in the case of psychology, modern research over the decades following Deming’s death has brought to the fore new insights into how our minds work and how they don’t work.

Perhaps one of the most important contributions of this research is the concept of the System 1 brain and the System 2 brain, as described by Nobel prize winners Amor Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the book Thinking Fast and Slow.

System 1 (S1) is the gatekeeper, which relentlessly analyses stimuli (circumstances, ideas, people, and so on) for threats and comforts. It rejects those stimuli that are unusual, new, and not experienced by the brain as being safe. Conversely, it accepts those that are known and believed to be harmless. S1 seeks constant reassurance of our current understanding of the world and is closely linked to our intuition.

System 2 (S2) represents our conscious analytical thinking. To understand an unusual or new concept, such as systems thinking or meta cognition, the concepts/stimuli need to get past the S1 gatekeeper and be understood and accepted by S2. For example, System 2 is what we use when we work on articulating a theory in an article, or when we try to solve hard math puzzles.

Let us expand on this: the linear, cause-and-effect model is typical of a two-dimensional operating system within the S1 and S2 brains and often manifests itself in our beliefs and decision-making process. This if/then thinking is often referred to as “common sense”. (“If workers would only pay more attention to their work THEN quality would be fine”, or “We have a problem with quality from one of our suppliers, let’s threaten the supplier with loss of work. That will solve the quality problem”.)

Another finding is that S1 is autonomous. It quickly forms a mental model with the information it encounters and that is what gets stuck in our head. Our brain automatically resists information that doesn’t fit our mental model or will try to assimilate it, thus preventing us from seeing the facts right in front of us and hindering real learning. Peter Senge tells of meeting a group of American motor executive who, following a study trip to Japan in the early ‘80s, told him: “They didn´t show us real plants… there were no inventories in any of the plants. I’ve been in manufacturing operations for almost thirty years and I can tell you those were not real plants. They had clearly been staged for our tour.” We, of course, know that the group had been showed the real plant. However, because it was a Toyota factory, it looked completely different to anything they had seen before.

This happens to all of us. But when we realize that we have unconscious biases and that system 1 is prone to oversimplification and sometimes being plain wrong, we develop an awareness that can make us better thinkers. In the workplace, the key to this is the visual management techniques that lean brings us. We can design meeting rooms, walls and boards that allow us to use both systems 1 and 2 more efficiently. We can engage our colleagues and employees in dialogue, and we can run practical experiments, PDCA cycles, to test our theory of knowledge.

THE “DNA CODE” OF A LEARNING SYSTEM

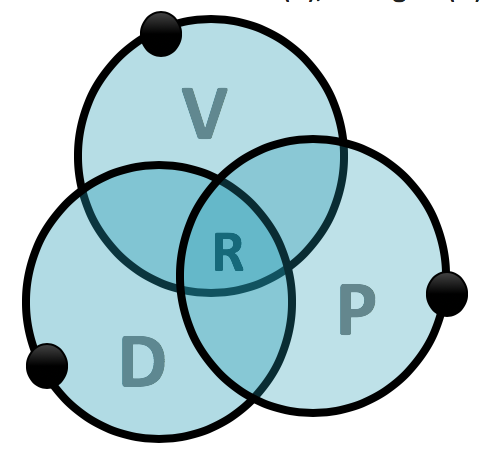

While working on our latest book, Learning Organizations, one of us (Bjarne) and the LOS Norge network asked themselves what the simple rules are that we can follow daily to increase the learning speed. What is the simple “virus” that could be a changemaker? What we discovered was the dialectic relation between visual information (V), dialogue (D) and practical experiments (P) – a very natural approach that can speed up learning and innovation significantly. Concretely, what does this mean? First, make important information visible in a way that it reinforces both System 1 (tell at a glance that everything is right) and System 2 (support problem solving and improvement work). Secondly, develop a hypothesis (Mental Model 1) through dialogue and make explicit what you expect will happen when you test your hypothesis. Finally, for the practice component, test your hypothesis with small experiments and learn as quickly as possible to develop a new mental model that is possibly closer to the real world.

SYSTEMS THINKING FOR BETTER LEAN PRACTICE

System thinking does not replace anything we have learned about lean. It reinforces it unequivocally. In fact, lean practitioners all over the world already practice systems thinking. By becoming more aware of this practice and the systemic nature of the lean tools, we can better support our real lean efforts. This starts with enabling front-line kaizen to better understand the current situation and develop an appreciation of the organization as a system. The prevalent consulting approach to organizational change, which is based on restructuring and programs that seek to implement lean as a tools-only methodology, doesn’t help us in this sense. Finally, a word of caution. Systems thinking does not give us leverage to control and influence systems as demi-gods. In fact, it does the opposite. A better appreciation of a system helps us better understand our own thinking, see lean thinking and practice as the education system that it is, and support kaizen efforts at the gemba.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – Lean book clubs as a way to boost learning and collaboration. A Norwegian firm that has been using them for a decade gives us a few tips on how to make them successful.

FEATURE – A laboratory testing services firm in Istanbul has turned to lean management to reduce complexity, shorten lead-times, and make its growth sustainable.

OPINION – A new publicly owned open-source technology promises to make direct, unmediated trade relations trustworthy, opening the door to an era of democratization and cooperation in global commerce.

INTERVIEW – Planet Lean interviews Silvia Cespa of Italy’s Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, a bank that boasts one of the most advanced IT departments in Europe. How did it get there? Through a six-year transformation towards lean banking.