A company-wide lean transformation: the impressive story of Simon

CASE STUDY — Simon, a Spanish leader in electrical mechanisms, went from growth-fueled fragmentation and operational complexity to a coherent, people-centric lean system spanning factories and offices worldwide.

Words: David Romero

I still laugh when I tell the story of my first day at Simon. It was 2015 and I’d just joined the company to help introduce lean concepts. I drove up to our plant in Olot, a town in northeastern Catalonia, with my boss. He had a simple brief for me on my first day: “Spend the day walking the factory and observing.”

A few hours later, in the car back to Barcelona, he asked, “So, David, what was your impression??”

My honest answer: “I didn’t understand a thing.”

The flow in the plant was so chaotic—processes scattered wherever there was space, kilometers of internal travel, and interruptions everywhere—that even as an experienced manufacturing manager I couldn’t make sense of how things worked. It reflected the reality of how the company functioned back then.

For decades, Simon had grown on the back of an exceptional local position in Spain. We were B2B, selling to distributors and installers who were fiercely loyal to the brand and trusted our quality. With the real-estate boom leading into 2008, orders poured in. When business is strong, you don’t always ask where value is leaking out.

Then the construction crisis hit, and volumes collapsed. We survived thanks to a wise earlier bet on international expansion (often through joint ventures or acquisitions to gain local know-how and compliance with national electrical codes), with China becoming particularly important for us. But by the time the dust settled, we realized that the old volumes would never return, our catalogue had exploded, electronics were accelerating product obsolescence, and our operations model no longer fit the business.

The symptoms were textbook: we had a lot of finished goods in our warehouses, and roughly half of our stock was obsolete by financial standards or with zero consumption in the past 12 months. New products launched with “fill the warehouse first” logic and, incredibly, launch stocks from products introduced a decade earlier were still lingering on shelves. Industrially, we were nearly self-sufficient—down to making our own screws and even running chemical baths—while machines and the workforce were aging and standards were thin. It was time to do things differently.

STARTING SMALL

The first decision we had to make was where and how to start. Rather than roll out training and hope for the best, we picked a contained pilot: Simon’s Martorelles plant, a smaller site focused on connectivity and project work. A perfect place to show Lean’s value fast.

I didn’t enter the company as Lean Manager. I came in as Plant Manager. That’s because in a transversal lean role, you have persuaded, while as a Plant Manager, you can set direction. This turned out to be a good call, as we needed momentum and clarity.

We attacked two fronts:

- Layout and Flow.

Over half of Martorelles’ floor space was warehouse. But we are manufacturers, not storage providers. We simplified flows with suppliers, removed non-strategic processes (like plastic extrusion, which ran only two shifts a week but occupied a quarter of the plant), and gave production space and logic. Stock fell and movement started to make sense.

- Organization and Culture.

We reframed the factory around the internal customer: everyone serves Production, where value is created. Then we replaced functional silos with Autonomous Production Units (UAPs)—mini-factories led by UAP Managers with people from production, logistics, maintenance, and quality. We kept plant-level transversal experts to protect standards. The UAP Manager says what matters and in what priority; transversals define how we do it to avoid each UAP becoming an island. We implemented this “the hard way”, overnight. The team, long experienced but lacking energy after years of routine, responded to a lean leadership style that listened to and empowered them.

Martorelles became a success story, and I was asked to take the model to the rest of the group.

AN INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY

Before moving machines around elsewhere, however, we stepped back. What do we want to be great at? We’re manufacturers of switches and mechanisms—not screws or chemical treatments.

A series of strategic choices followed:

- We stopped in-house production that wasn’t core (for example, screws and chemical baths) and started using specialist suppliers.

- We reconfigured our EMEA operations, streamlining production and opening a new plant in Romania.

- We relocated the Lighting business from Girona to Martorelles where a project-driven model fit better. We supported layout improvements in Brazil and India.

A key learning hit us at this point: projects that change how people work are hard to sustain if you push them onto teams. As soon as central support—aka, me—left, projects degraded. We had to flip the role of Lean, from pushing change to coaching people to enable it, and make problem owners lead. This insight set up the next stage in our journey.

FROM PROJECTS TO A PROGRAM

We moved from annual, short-term initiatives to a multi-year transformation program. We introduced our “Simon Temple,” a model that had clear pillars, foundations, and a four-to-six-year vision.

Once again we needed a pilot, and our choice was bold, to say the least: Olot, our most complex plant technically and culturally.

Why Olot? Because we thought, if Lean can work in the most demanding environment, it can work anywhere.

Our program to transform Olot consisted of six phases, or projects, as we called them.

First of all, Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). We wanted to introduce a pull system, but we were running old automation with OEE in the 30–40% range after years of maintenance under-investment. With such variability, a pull system would implode. We started with TPM to stabilize the equipment.

The second project focused on the Macro Layout (the end-to-end flow, which had been clearly in need of fixing since my first visit). Over decades, processes at Olot had been plopped wherever there was space. We redrew the factory so product flows from reception to shipping with minimal backtracking, slashing internal movements and WIP.

At this point, once the big flow was set, we could move on to our third project: the Micro Layout. We went process by process at the gemba, standardizing the work with a people-first lens and attacking muri, mura, and muda wherever they appeared.

The fourth project entailed further standardization. The “know-how in people’s heads” had to be moved onto paper and into standards. On the product side, R&D joined the party: historically, every series had a different “motor” (the functional core), scattering volume across too many variants. We began moving to platforms.

Then came the pull system. Only after stabilizing our machines, untangling the flow, and standardizing the work did we shift from forecast-push to kanban pull.

Finally, we extended the UAP logic into value-stream-like mini-companies, aligning accountability, KPIs, and daily management around the generation of end-to-end value.

We called TPM and layouts the hard projects (those that required money and resources to progress), while pull, standardization, and mini-companies were the soft ones (those that were more cultural in scope). We changed leadership accordingly: once the hard work had shape, I moved into the Plant Manager role to lead the cultural transformation, while the former plant manager focused on industrialization.

Mid-transformation, we launched the 270 series, the first product line conceived explicitly with lean principles in mind:

- One-piece flow by design: dedicated injection and press capacity next to the assembly line, no shuttling to warehouse and intermediate stocks at the line.

- Platform thinking: the “motor” became our future standard. We retrofitted the best-selling Series 75 with the 270 motor to concentrate volume and justify the investment in new, better equipment.

In total, I spent four years deeply involved at Olot (one as Lean, three as Plant Manager). By 2024, the system wasn’t “finished”—it never is—but it was running. The plant changed dramatically. Before, we rarely brought customers to Olot. The plant wasn’t ready to showcase, as its layout and environment didn’t reflect the quality of our products. After the transformation, we opened the doors. We now host three to four customer visits per week, often financing part of installers’ travel to make it easy. The plant became a sales asset and a source of pride.

Simon’s CEO then asked me the natural question: “Can we apply this lean model to administrative work?” That kicked off Stage 4.

THE LEAN OFFICE

In 2024, Simon created a Lean Office at its corporate headquarters to bring Lean Thinking beyond the factories. The new team focused on three main fronts: aligning strategy, improving office processes, and sustaining manufacturing excellence.

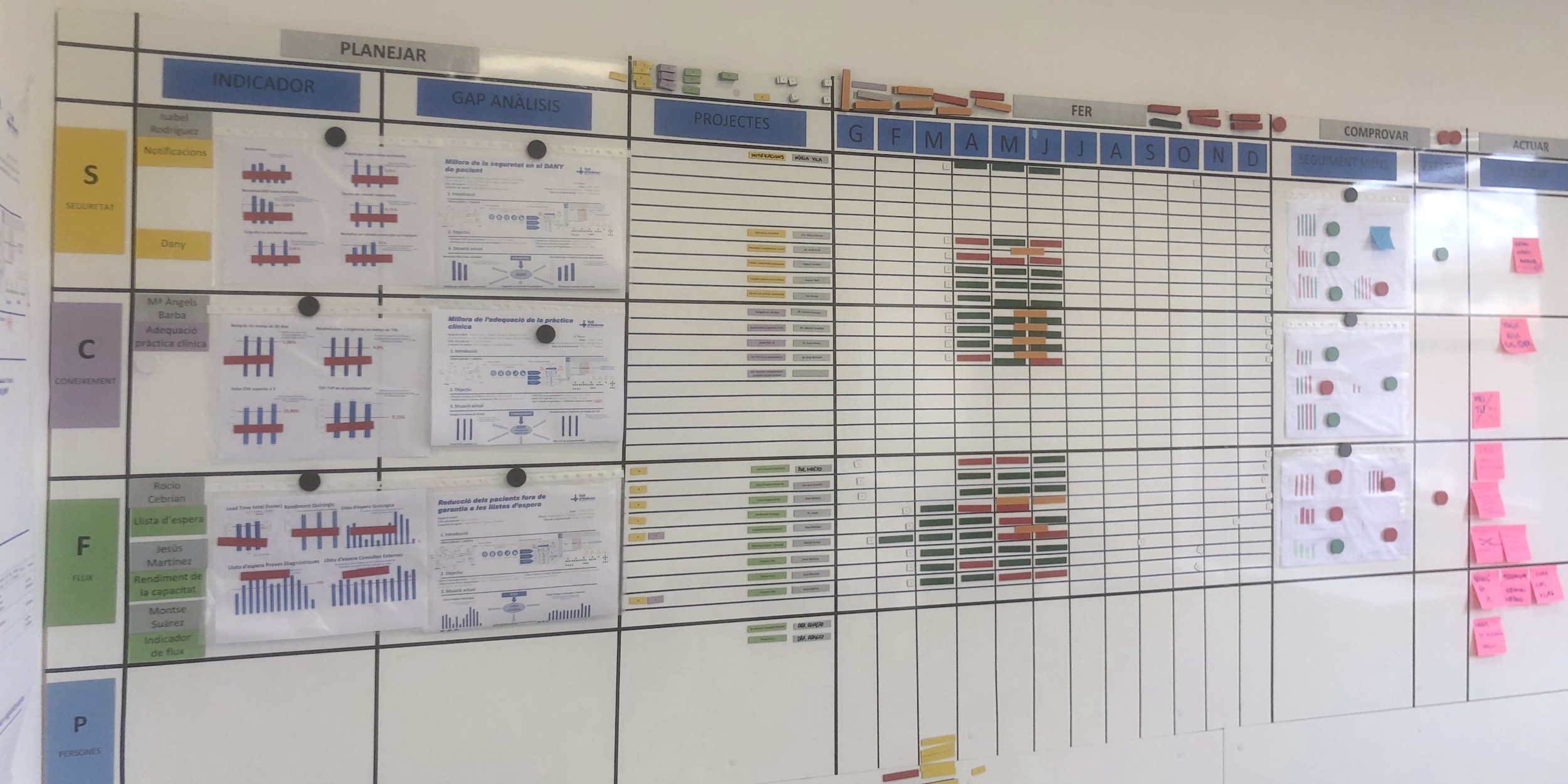

First came strategy deployment through the adoption of Hoshin Kanri, which set a shared vision toward 2030 broken into two-year horizons. The company began cascading this approach from headquarters to regional teams in EMEA and LATAM (with APAC progressing more slowly due to cultural and market challenges).

The second focus was process improvement in the office environment. With guidance from the Instituto Lean Management, Simon mapped its key administrative and commercial processes and chose several critical ones for in-depth Value Stream Mapping: New Product and Process Development, Go-to-Market, and “Configurados”—custom, engineered-to-order products that often challenged internal systems.

Finally, the Lean Office worked to sustain and extend the manufacturing transformation by developing a Lean Self-Assessment tool. This diagnostic is now used alongside VSMs to establish a clear, fact-based starting point for every plant before expanding the lean model worldwide.

Each process improvement initiative was led by the department head most affected by the problems, supported by an executive sponsor, a Lean change agent, and a cross-functional team. These clear roles kept ownership where it belonged and prevented improvements from becoming “someone else’s job.”

Of course, none of this would be possible without a solid training approach (in two years, it allowed us to train 78 Green Belts and 6 Black Belts—the latter allowing us to start developing White Belts internally) and without a strong system for governance (we are formalizing cross-functional progress teams for each main process and departmental improvement teams for local kaizen efforts).

Supporting all of this is a leadership team who understands our job is to make things happen, push through the daily noise, and keep focus on the few vital priorities that make tomorrow easier than today.

Learn more from David about Simon's lean journey at next week's Lean Global Connection. Register for free here.

Read more

OPINION – What happens when a senior executive jumps the fence and finds himself having to drive the very same change he was asking others to create?

CASE STUDY – Catalonia’s largest hospital is undergoing a successful transformation – supported by pioneering hoshin experiments – that has already turned it into a poster child for lean healthcare in the region.

FEATURE – Focused experimentation and kaizen can lead to impressive results in as little as one day, as the story of this Hungarian company shows.

ARTICLE - A-ha moments... we have all had one at least. In this personal account, the author reflects on what his own experience has taught him about changing our mindset and being stuck in our ways.

Read more

CASE STUDY – A very lean system that runs like clockwork and constant attention to customer service enable Barcelona-based 365.café to achieve the impossible: supplying 55 bakeries out of a 650-sqm factory.

CASE STUDY – This automotive parts supplier based in southwest Spain is discovering the power of lean thinking applied to recruitment and Human Resources.

FEATURE – Visualizing the work, increasing customer focus and changing the way to interact with employees has helped a family-run Dutch building maintenance and renovation firm to transform itself.

FEATURE – How lean daily management helped a Brazilian construction company to stabilize production in a tailing dam elevation project.