Scaling without breaking

CASE STUDY – Lean allowed NGNY to evolve from creative improvisation to structured performance by redesigning operations and standardizing processes – achieving reliable deliveries, built-in quality, and a cultural transformation.

Words: Maite Viladomat, Jordi Esplugues, and Tomeu Ventayol

Since its founding, our company has had innovation as a primary goal. The name itself comes from the Catalan word for wit (enginy), symbolizing our creative drive. From day one, we also knew we didn’t want to just design machines; we wanted to build them too.

At first, manufacturing everything in-house was manageable, because we were producing only a handful of machines per year—each slightly different, each tailor-made for a customer. This customization thrilled our clients and energized our small team. We could spend time between orders rethinking designs, improving them, and testing new ideas directly in production. The problem appeared when NGNY started to grow, and the large number of unique orders turned excitement into chaos.

By 2017-2018, it became clear we had to professionalize our manufacturing operations. We were very dedicated to change, so much so that we couldn’t resist improving something whenever we saw a flaw. This is normally a strength, but it was becoming a liability for us: we were constantly tweaking machines, and at the same time, engineering change requests became more and more frequent and documentation inconsistent. The lack of standardization started to hurt us.

When we had 15 machines a year to work on, we could control the situation. But with many more being manufactured, we didn’t even know what configuration each machine had. We had no consistent bill of materials and each machine was something of a piece of handicraft that depended on the experience and ability of our workers. We were improvising on the fly, and that was no longer sustainable.

Our production floor was cluttered with parts scattered everywhere. There were no clear zones, no inventory control. With the best intentions and a will to keep the work going, people would take parts from storage without logging them, which led to recurring shortages and delivery delays. We worked weekends. We missed deadlines. We were burning out.

About two years ago, we hit a breaking point. We were scaling up for a global contract that later got reduced, but the stress of preparing for it exposed all the cracks in our system. That’s when we reached out to the Instituto Lean Management and began working with Anna Voltes and Nestor Gavilan.

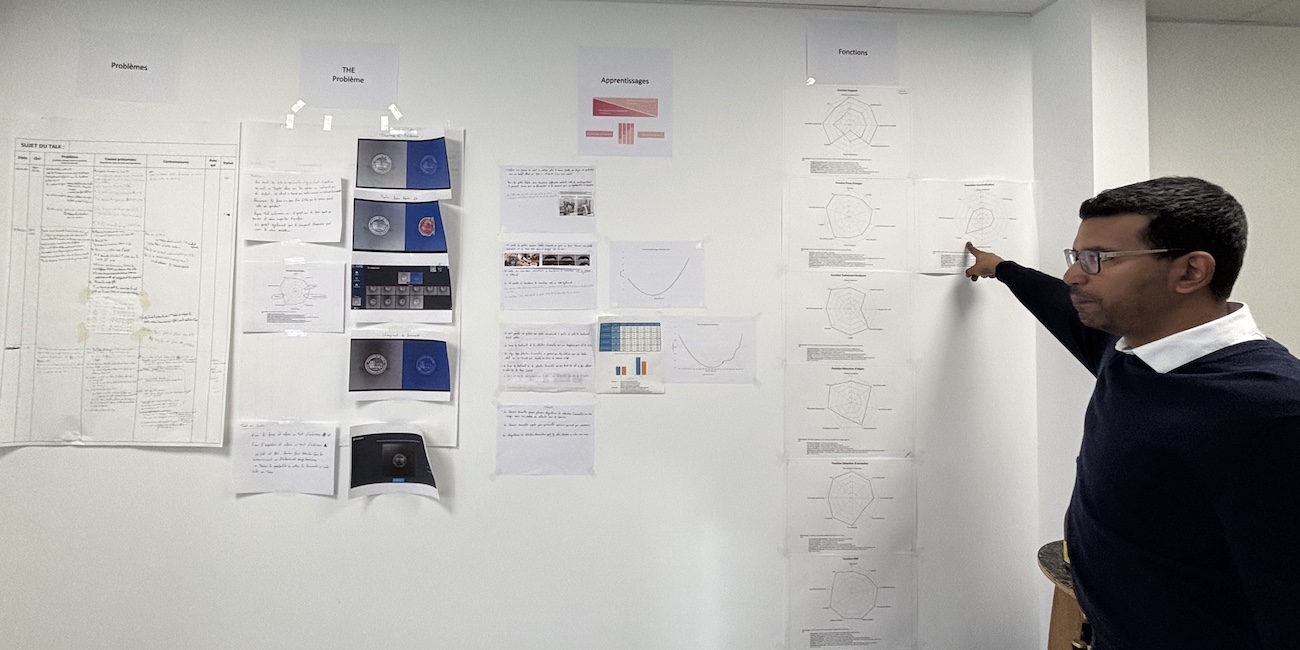

Our initial request was simple: help us define the role of an industrialization manager and figure out the kind of profile we had to be looking for. But that conversation sparked a much deeper reflection and eventually led us to initiate a transformation. We began rethinking the structure of our operations, including a major internal reorganization, using the Lean Transformation Framework as a model. This meant defining the problem to be solved, establishing standardized processes, training people, and setting up a management system, all while maintaining our distinctive culture and reinforcing certain aspects like A3 problem solving.

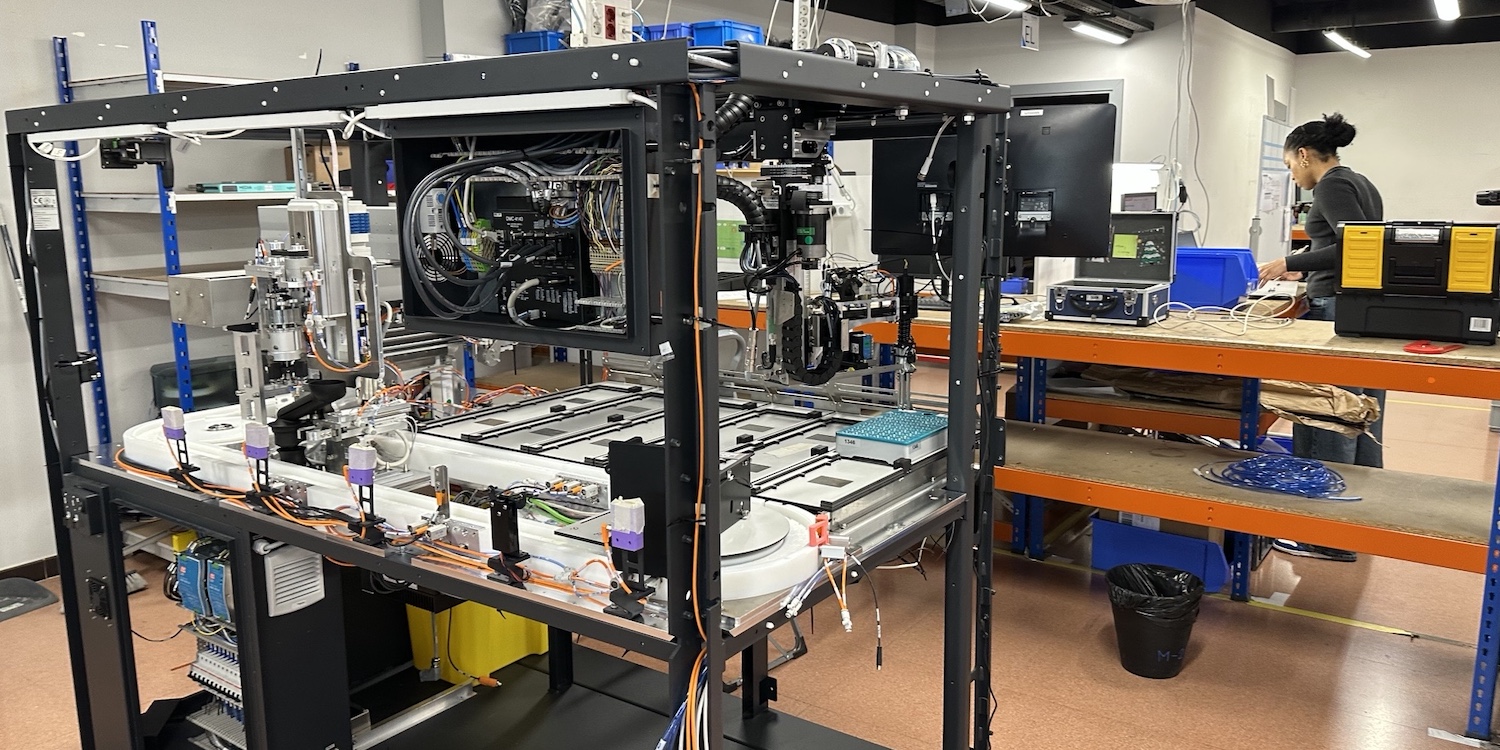

With Anna and Nestor’s guidance, we tackled the fire head-on with a series of actions – all taking place in parallel with the key aim of protecting the “pacemaker” of our process, the assembly of the machines in cells (we call them ZAP, Zonas Autónomas de Producción).

We started tackling our stock system, overhauling the warehouse, blocking unauthorized access, and doing a complete inventory. At the same time, we built our PMC - a standardized phased production plan for each machine configuration – so our assemblers had clear guidance. Before that, they worked from memory, and everyone had their own way of assembling machines (which, of course, was better than anyone else’s).

We redesigned our shop floor. We introduced a logical flow: each cell (ZAP) had an input shelf, a workspace with a final machine assembly area and a workbench for sub-assemblies, and an output zone. We limited material per phase to avoid clutter and created a mini-buffer to support flexibility without chaos. We set one firm rule: no boxes could leave the warehouse unless they were complete.

We also addressed picking. Previously, it was done with markers on paper – which often carried unclear information and occasionally got lost. We digitized it with spreadsheets tied to the PMC phases, so we knew exactly what was picked, what was missing, and what was ready.

Another challenge was planning. We started managing both macro and micro planning, using two different approaches. The macro planning is based on a weekly meeting and leverages a high-level dashboard we set up. It has burndown charts to estimate realistic completion dates, and a color system indicating the status of every ZAP, so that we know in real time when we expect each product to be ready to ship and if there is any risk we might not make the expected schedule. The micro planning is based on a daily management system called APM: Almacen, Planificación, Montaje (Warehouse, Planning, Assembly). These meetings helped us to more clearly identify the problems we were experiencing. We tracked operator time per phase using simple timers, eventually creating burndown charts to estimate realistic completion dates.

Changes were also made to the way ZAPs operate. First, we won’t even initiate production of a machine without checking first if there are any stock breakages that will impact the assembly schedule. Once production starts, in each ZAP’s panel, we have a checklist and an andon system tracking the progress on the machine and alerting us if there is a risk it is getting delayed. If a machine is projected to finish ten days before its deadline, the andon marks green. Between five and 10 days, it marks yellow. Less than five days, it marks red. This visual dashboard tells us what problems we need to focus on to clear the obstacle and helps us decide whether or not we need to take further decisions to mitigate risk (like starting assembly even without a complete picking list).

To better manage and keep track of the design changes we made to the machines, we introduced an Engineering Change Request (ECR) system: we set up a triage-like system in which a team assesses each ECR, performing an impact analysis, to decide which changes will go ahead.

We also standardized terminology. We built a dictionary of terms and created training material. This wasn’t just about Lean tools; it was about changing our culture. Our people were used to improvising, to being heroes. Transitioning to standardized processes was tough, as some of them felt it limited their freedom. But over time, they saw that it reduced stress and made their work more predictable.

We also introduced A3s to align objectives and responsibilities. These became our monthly rhythm, where we reviewed progress on problems we had highlights through simple green-yellow-red statuses. Now, for the first time, we have the peace of mind to think beyond today.

One of our biggest mindset shifts was moving from urgency to quality. Our operations team now focuses on ensuring machines function perfectly during assembly activities – following the concept of “built-in quality”. To do that, we meet regularly with the service team to capture and learn about any startup issues occurring in the field. That makes a huge difference.

Before our transformation, about 50% of our machines shipped late, often requiring costly overtime. Today, that number is zero. We haven’t missed a delivery in over a year. Our change control process is now rigorous. Engineering changes are prioritized and managed through formal ECRs.

Today, our system isn’t perfect, but it’s solid. It allows us to predict delivery dates, track progress, and react to problems in advance. We’re finally in a position where we can improve quality systematically. And should the day come when we scale to 20, 40, or even 60 machines, we know our foundation is strong enough.

Our lean journey is intense and humbling, but we are happy we could move from firefighting to anticipating, from improvisation to structure. More importantly, we are seeing our culture shift, as we commit to the pursuit of excellence.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – The conflict unfolding in Ukraine acts as a tragic reminder of the threat posed by despotic, unapproachable, and paranoid leaders, says Sharon Visser.

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – Ahead of the holidays, for his last column of the year, the author reminds us of the power of sharing. Go out and spread the lean word!

CASE STUDY – Some blamed lean for the shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) in first wave of the pandemic. This small Norwegian producer of disposable bedsheets used it to establish and ramp up the production of medical gowns for healthcare workers.

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – The author visits the office of Theodo France and learns how the lean digital company is leveraging lean thinking and practice to support its ongoing growth – even through the pandemic.

Read more

CASE STUDY – This French firm transformed its engineering approach through continuous learning, radical redesign, and user-driven innovation, evolving into a lean, resilient company with a strong culture of development.

INTERVIEW – Today’s story takes us to Iceland, where a senior leader in a utility company introduced cellular thinking to her team in a bid to improve flexibility and better working conditions.

FEATURE – With an open-minded approach to improvement tools, a long history of quality and engaged top leaders, wire manufacturer Ducab aims to fulfil the strategic needs of the Emirates.

BOOK EXCERPT – In the introduction to his new book, Art Byrne reflects on his lean journey and explains why to understand lean one must change their mindset.