Turning around a business using lean construction ideas

CASE STUDY - Addressing failure cost and introducing a new quoting process are only two of the ways in which Dutch construction company Dura Vermeer is successfully achieving a lean transformation.

Words: René Aernoudts, President, Lean Management Instituut

In 2011, I received a call from Ronald Dielwart, the CEO of Dura Vermeer Construction and Real Estate, one of the largest construction companies in the Netherlands, who invited me over to discuss some of the issues the organization was facing.

Dura Vermeer had been applying lean principles for four years, Ronald explained to me during our first meeting, but despite their efforts bottom line results failed to materialize. Additionally, in the aftermath of the financial crisis the company was struggling, its core business being to build new houses and offices. “What am I doing wrong? Why isn’t lean working?” Ronald asked me.

I organized a workshop for him and his board team to try and create a strategic A3. They booked two hours for it. I knew very well it was not going to be enough, but I also knew it was important for them to learn on the go. It didn’t take long for them to realize we were onto something, and when after two hours all we had managed to fill was the background box, they said: “Okay, let’s book another six hours next Friday!

I was not convinced about lean at first. After I got to know René and he told me about the principles and showed me a number of successful cases, however, I realized lean was actually a point of view on business management that made sense to me. I knew it could bring interesting results to Dura Vermeer. I used to think that so long as you have the best people you would have the best results. I was completely neglecting the process side of things. What I learned from René – and this was probably the main change in my way of thinking – is that the process should never be ignored. With an excellent process in place, how great your people are doesn’t matter as much. The results will come.

Having an external sensei has a number of advantages: as I have learned with my work with Lean Management Instituut, they bring in new ideas, thoughts and insights.

Ronald Dielwart

The first iteration of the A3 was, as it often happens, quite straightforward. Four versions were produced in the course of the following three weeks.

In 2010, attempting to formulate a strategy and encourage people to follow it, Dura Vermeer had come up with a 39-page plan. Still, one year later results had not arrived.

During one of my chats with the company's management, it became clear that one of the elements hindering the progress of the lean implementation was the struggle to identify what the board themselves could do differently to have a bigger impact. The 39-page plan had been sent around the organization without follow-up or support from management.

"We had applied lean for quite a while, but we had not implemented it as part of our strategy. It started from the bottom up, with a few enthusiastic initiatives on the building sites, but a lot of people in our management team were reluctant. They certainly were not ambassadors of the methodology. In other words, lean was isolated. Resistance is common before a proper understanding of lean is built."

Ronald Dielwart

Our conversations proved extremely useful to understand what Ronald and the board had been after all along. They wanted to make the work more predictable, and to be in control of the processes. "I did not want to find out we were losing half a million at the end of a project, when there is nothing to do, as opposed to during the process when action can still be taken," Ronald said to me.

The observation of the current state revealed the issues we would have to focus our lean efforts on: the biggest one seemed to be failure cost, with its negative repercussion on profit.

The most evident form of failure cost for Dura Vermeer resulted from the company's tendency to buy land hoping they might one day be able to build on it, an exercise that, with the financial crisis, proved costly and ultimately dangerous. It became evident that some of the affiliates' (Dura has eight affiliate companies in four regions) costs could be controlled more effectively: they could work around a specific budget, for example, or plan for a certain amount of hours to be worked or for the materials they were going to need. At the end of the line (in this case, at the end of the project) the company would measure what items and metrics were in spec or what weren't.

KAIZEN #1

Dura Vermeer's turnover at the time was €700 million. Failure cost totaled €26 million, while profit only reached €11 million. One of the turning points in the implementation was when, talking to the board, we translated the €26 million into the number of Ferraris we could have bought and completely destroyed by the end of the year.

There were only two things the organization could do to increase profit: double the number of projects they sold or shrink the failure cost. They decided to tackle the latter first, giving themselves the goal to reduce failure cost by 30% each year.

While going through the A3 process, company management mainly focused on three elements:

- What they needed to change in their behavior;

- What elements they had to concentrate on in their bid to change (failure cost being the first one);

- The need to create a standard approach to the work across the organization, which would make it easier to compare subsidiaries and to steer the company in the right direction.

We concluded that once a month the board would check on the progress in following the plan detailed in the A3.

I was asked to lead one five-day kaizen event specifically on failure cost. We came up with a group of 10 people working in every level of the organization and in the subsidiaries. Most of them had never worked together before and with them we mapped the process, from selling a project to delivering a building.

There was no system to keep track of failure cost at the time. To gain more visibility of the problem, I asked all the participants to meet with me once a week. At the end of the first meeting, I asked each of the participants to ask three leaders to identify the failure cost in their projects and their idea of what caused it, just to get a feeling of the situation.

At the second meeting, it was very surprising to see the exact numbers they came back with. One had identified €92,000 worth of failure costs, another one €125,000. I then realized they had a better understanding of what was going on than they originally thought.

All of a sudden we had 30 issues to look at. We picked the six or seven we'd be focusing on. One of them, for example, was related to the quoting process. Every time it received a request to build, say, an office, the company spent six weeks calculating costs and coming up with a quote. It then sent the proposal and met with the client, who 90 per cent of the times asked for a lower quote. Dura Vermeer pledged to come up with a second quote in two days, even though this was not enough time to consult with as many as 70 suppliers. This led to guessing, and some of those guesses were pretty off. But the company still had to deliver to the customer.

If nine clients out of ten asked for a lower price, why not calculate alternatives from the very beginning (thinner walls, cheaper roofs, etc) as opposed to using guestimates and ultimately losing money?

This was one of the root causes of failure cost that we found. On day four of the kaizen exercise we came up with 23 solutions, which we brought down to seven (the calculation of alternative quotes being one of them).

Another one was the introduction of oobeya boards in the preparation phase as opposed to just in production. Sometimes there was little time to calculate the costs of a project and come up with a proper execution plan. For example, if a project commissioned by a government body got delayed because of red tape, all too often those supposed to work on that project were not even told.

As a countermeasure, we started visualizing all the projects, clarifying who's responsible for what, who's part of a specific project, what the timeframe was, and so on. We also introduced the green/red system to make waste (and therefore possible causes for failure cost) as visible as possible.

The wake-up call for one of the directors came when the oobeya board showed that two of his projects were in the red area. As project lead, he was shocked as it did not expect to be part of the problem. That changed his mind.

"When you use visual boards, you have a standard format and a standard frequency to follow. They force you to focus on the important information. One of the biggest advantages for Dura Vermeer was that they allowed us to discuss results and figures with management. Sharing all the information on the boards made it easier to talk about problems, because it gave everybody the same visibility over them, which in turn made it possible for us to take action."

Ronald Dielwart

Eventually, the organization was able to pinpoint the five root causes of failure cost, which turned out to be a very hard exercise:

- There wasn't a good relationship with suppliers;

- They were not booking the hours correctly (because they didn't know how many they needed);

- The process of transferring work from preparation to production left many unanswered questions for people working on the sites;

- Information was lacking or arrived late;

- The company was constantly under pressure to come up with a new price and offer.

Countermeasures

- Being proactive in proposals to clients;

- Using visual management (oobeya) both in preparation and production. Dura Vermeer had to find a good way to manage projects without spending hours and hours in the oobeya. This resulted in the introduction of the green and red magnets (there were blue ones, too, meaning a project was on hold);

- Standardizing work in production: plans with subcontractors, daily startup talks on sites, visual management on site (board), 5S, etc. At the beginning of every new project, production people attend the kickoff session;

- Developing a standard kickoff and coming up with a way to have structured meetings (one with the team, one with suppliers);

- Improving the escalation process: what happens if quality is not good or if the process is taking too many hours? How does the organization react and escalate? This is partly done at the meetings by the boards, but people still found it difficult;

- Developing partnerships with suppliers: co-planning and bigger focus on cost saving, agreements on how products are delivered, performance monitoring, etc.;

- One person is responsible for the whole process, as value stream manager.

Our hypothesis was that these seven countermeasures could help. We launched the experiment by providing a 12-hour training to employees. We also reached out to the managers of each of the subsidiaries.

Most people agreed to participate, and even the reluctant ones eventually got on board.

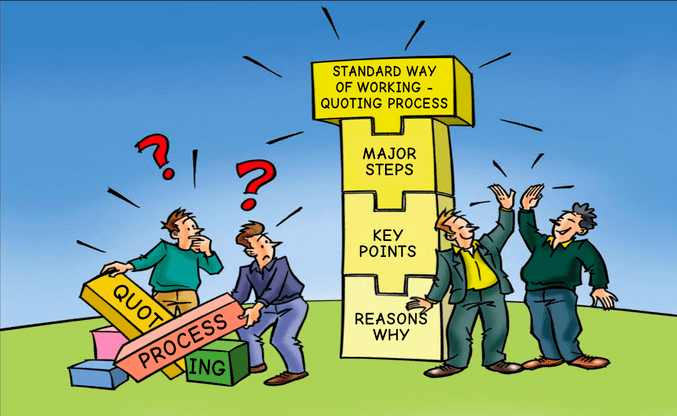

"Each affiliate of Dura Vermeer had its own way of managing their processes. The standard way of working was difficult to introduce, and explaining the principles of lean and their advantages in a very clear way was critical in the early stages. We had to force our people to live by those principles at first, but they soon saw the value in doing it and resistance gradually disappeared."

Ronald Dielwart

One year ago, in 2013, Ronald presented the results of this experiment: in less than two years, failure cost went from €26 million to a little under €6 million. However, the most important outcome is that people are now in control of the process.

This is, as ever, a work in progress – occasionally, the organization still lacks standard work. It's hard to change a culture, and to try and make more progress in this field the board decided to change its approach: instead of sitting in their office twice a month reading a progress report, each of the board members now visits a subsidiary in the morning (to attend the local oobeya meeting) and then meets with the rest of the board in the afternoon to share the findings. This system goes a long way to clarify whether local teams are in control of their processes or not.

"Going to the gemba is the most important part of a lean transformation. Seeing, experiencing, and feeling what is going on in the company is key. Every Monday morning I now visit a management meeting, which allows me to offer advice, support, and suggestions for improvement. This way, in two months I have attended every subsidiary's oobeya meeting, which really helps me to understand what is happening across the business. Management really is better informed these days, and people notice how different things are now that the management team is directly involved in the process."

Ronald Dielwart

KAIZEN #2

The second kaizen was carried out to increase market share. We did it by implementing a similar exercise. We wanted to understand how Dura Vermeer could create healthier growth without underselling just to get work (which seemed to be the tendency lately)./p>

One of the trends I saw was that less and less work was given out directly. Most of it began to happen through tenders.

It's a tough process, and one that dramatically changed the construction market: in certain areas, the percentage of tenders went from 10 to 90%.

Dura Vermeer had to focus on how to improve the process and increase the number of projects it secured. After carefully observing the market and the company's behavior within it, we came up with six countermeasures for Dura's problem with market share:

- Creating more opportunities;

- Establishing a better filtering system, to isolate the projects the company had no chance of getting (for example, if there is a tender to build a protestant school in a village where only one protestant builder normally operates, what are the odds of winning that contract not being a protestant company?);

- Increasing scoring percentage (that is, the number of contracts the organization actually wins – one is six, two in seven, and so on);

- Sharing more knowledge between subsidiaries (for example, when one got a request to build a laboratory despite not having laboratories in their portfolio, another subsidiary with experience in the field stepped in to help);

- Implementing the red stream/green stream system;

- Turning clients into ambassadors.

Once again, we went to all the subsidiaries with this set of potential solutions (this was about six months after the failure cost kaizen took place). After some initial struggles to ensure the improvement would not become the sales guys' prerogative, we managed to achieve very good results.

"One of the characteristics of the construction market in the Netherlands is that even the largest companies have a small share. When we started with lean, Dura Vermeer had 1.8% of the market share – now we are at 2.3%, and we are very proud of this achievement. Our goal is to reach 3% soon, and we will get there."

Ronald Dielwart

KAIZEN #3

The third problem that I worked on with Dura Vermeer was the preparation process for quotes.

The problems we identified were:

- Price was too high compared to the competition;

- Many opportunities were lost because of the price we offered, even though Dura Vermeer scored well in quality;

- There was too little capacity in the preparation process to effectively pursue the right opportunities;

- There was no insight into capacity vs requests.

We went through another value stream exercise and set a few targets (one of them being to win 30% of the tenders the company participated in).

Here's the countermeasures we came up with:

- Introduction of Job instructions for the tender process, in order to put in place the right standards with the help of the people doing the work;

- Making sure the directors were available to sign off a proposal (tenders cannot wait a week or two just because directors are not available) – this was achieved by consistently explaining why it was important to win a specific project, and so on;

- Improving communication with subsidiaries to better understand capacity and realize what tenders to go for;

- Determining price depending on what customers might be willing to pay (as opposed to looking at cost and margin). Here's an example: offering houses for the same amount as that banks are willing to give out for mortgages (about €190,000). It's essentially looking at the market (in classic Toyota style) to understand how to offer something the customer will buy at the right price (this really got the company's attention). It's "Price-minus" vs the traditional "Cost-plus" approach;

- Being able to calculate, within 1.5% accuracy and in just a few hours, how much a building is going to cost. Given certain criteria (square meters, materials, etc) the company should be able to foresee cost without going through all the suppliers;

- Starting to look at how people are going to use a building. What is important for a customer? This was a way to inject creativity in the company's projects while going the extra mile to look at the social aspects of a neighborhood, and it required the input of different types of professionals;

- Making a clear choice to involve external advisers in some of the activities the customer might ask the company to carry out.

"We operate in a very competitive market, and we understand how critical listening to the customer carefully is. Our 'Price minus' approach was instrumental in changing the way we prepare quotes. When we speak to our customers, we understand what they perceive as value and we can deliver a project accordingly and at the right price. We are now thinking in a different way, which enables us to make a profit even with the small prices we offer: given a certain budget and our customer's requirements, what can we deliver?"

Ronald Dielwart

These countermeasures seem to be working: one of the subsidiaries was aiming for €160 million worth of contracts. Before the end of May, it was already at €97 million, with 50% of tenders it entered won.

TO CONCLUDE

The lean implementation at Dura Vermeer is still a work in progress (isn't it in every organization?), but the number of contracts won is increasing. At the same time, failure cost has been reduced dramatically. The biggest change, however, is in the mindset: a culture of continuous improvement is starting to take shape in the organization. People own their work and are in control of it. Sticking to countermeasures that make sense seems to be bringing great benefits to the company, and as a consequence people are engaged in our attempt to take the business to the next level.

"Our goal is to fully establish a standard way of working in which everybody believes. We want all our affiliates to implement our best ideas, and in order to do so we need to build on our collaboration with one another. We want to become a smarter, learning organization.

When it comes to lean, a CEO must be a believer himself/herself. Only then can you give other senior executives direction and convince them of how game changing the methodology can be. You also need to be very clear that the use of lean is not optional. Persistency is the secret."

Ronald Dielwart

THE AUTHOR

Read more

CASE STUDY – Hotels of the Palladium Group are implementing Lean Thinking in their housekeeping departments to improve efficiency and service quality.

CASE STUDY – Over the past few years, DBS Bank in Singapore has undergone an extraordinary turnaround inspired by lean. Here, the COO explains how the company has become the world's "best digital bank".

CASE STUDY – This packaging company in Catalonia has been able to cleverly balance the resolution of urgent problems and the advancement of the lean transformation. But what to do when the burning platform is no more?

VIDEO - The CEO of a cancer center in Brazil gives us a tour of the their obeya room, taking us through their strategy deployment and explaining how it supports their mission of reducing the burden of cancer.