The harvest of the future

INTERVIEW – This agro-industrial business in Colombia is applying lean thinking to its harvesting process. The harvest manager explains the difficulties and opportunities encountered on the journey so far.

Interviewee: Luis Guillermo Amu, Harvest Manager, Manuelita Azúcar y Energía

Interviewer: Juan David Ruiz Valencia, President, Lean Institute Colombia

Juan David Ruiz: How did it all start? When did you get bit by the lean bug for the first time?

Luis Guillermo Amu: I first learned about lean thinking over 10 years ago, as I studied to become an industrial engineer. Lean was also present in the thesis I wrote. One day I read an article by an Australian named Andrew Higgins, who said that harvesting technology has already reached state-of-the-art level and that the only way to make steps forward in agriculture is to deploy a lean system. That idea had me thinking, and after a while I decided it was time to try to apply lean to the harvest of sugar cane at Manuelita Azúcar y Energía.

JDR: What obstacles did you encounter when it came to the harvest?

LGA: First of all, it wasn’t easy to “sell” lean to people in our organization, where the culture was very much based on the idea that results only come from investment. Changing that paradigm was difficult.

At the beginning, I was the one who started telling them that we could achieve good results without investing money. I repeated that for a few years, while running experiments that would give them empirical evidence that it was indeed possible to improve things without spending money. I didn’t want them to take on lean because the “boss had said so”.

There is no doubt that the hardest part was ensuring I would not be the only one pulling my weight in the transformation. I wanted everyone to participate, to be committed to the journey ahead.

JDR: What was the problem you wanted to solve when you decided to embrace lean thinking?

LGA: Our costs. With the price of sugar being quite low, we started to ask ourselves what we could do. Lean gave us the answer we were looking for. We began by looking for some of the lean tools that would allow us to do more with the same resources (or the same with less). Ideally, we wanted to do more with less resources. At that point, we analyzed the key processes in the harvest and tried to identify the biggest variables in each of them (that is, those factors we couldn’t predict and had no control over).

We also looked into our best practices when faced with such variables and how we behaved when we encountered a problem. We started to pay more attention to how we were doing, identify, document and validate our best practices to then turn them into standards – which is what we are currently working on.

Before long, we realized that the data we were gathering internally was better than that from our reference plantations in Brazil and started to wonder why we weren’t learning more from our own team.

JDR: What were the lean tools you used as you made your first steps?

LGA: First, value stream mapping, through which we discovered lead-time. The people who participated in the VSM exercise came from both operations and other functions that are not linked to the harvest – from machine operators to engineers, mechanics to managers. We had people who didn’t know much about the actual harvesting work.

We went on a gemba walk together and, through it, we learned about things that to many of us were simply part of the way things were. We got feedback from our team members and identified waste in the work. We proposed a future state for our VSM and started to think about how we could get there.

The best part was that none of the 130 problems that we identified at that time required any investment!

We also used the A3 method, as our people started to attend workshops organized by the Lean Institute Colombia. The A3 is an interesting concept that we are getting better at. The objective for us is not filling the different sections of the sheet, but to train our brains to solve problems. It was difficult to get people to understand that the A3 is a tool, not an end. People are starting to get it. They now see that they can even challenge their colleagues’ A3s and how that typically improves them. The results we are achieving are getting everyone on board.

JDR: How does the management system work? What’s the routine for leaders?

LGA: Each manager gets together with her team every day to track the most critical indicators. As managers, we get together – once a week, on Tuesday morning (but really we see each other every day).

We track our tasks using a Kanban system that tells us what’s in process, what the new tasks are, what actions are being executed, which tasks are complete. (We also track some tasks by means of our A3s.) That’s how the meeting begins.

The meetings have changed over time. We still look at the data to understand what happens month by month, but in the weekly meeting we have started to discuss the improvement work we are doing and what the most common problems are.

Our management system allows us to raise and tackle problems systematically and effectively. Problems no longer have the better of us. It’s how we run things in our harvest these days.

JDR: What’s the role of leadership in all this?

LGA: The role of leadership couldn’t be more important. It may sound like a bit of a cliché, but to me leaders have to inspire their people. I am not here to give people orders, but to empower them, challenge the solutions they come up with, and support them when they are worried about something.

Other leaders should do the same with their teams, and their teams should do the same with people at the front line. We have to get all the way there. For instance, a tractor operator has to understand fuel consumption, if he is delivering as much as sugar cane as is needed, if their clients are satisfied, and so on. We are slowly getting there.

At Manuelita Azúcar y Energía, we don’t do lean as well as our work. Instead, we are integrating lean thinking into our way of working. Many great ideas have gone nowhere because people worked for the idea and not what lies behind it. I always tell people: if we are not spending time on something, it’s because it’s not critical. That’s how we channel our energy.

JDR: What have you learned so far?

LGA: The most important lesson I have learned is that lean can only succeed if people engage in it. You have to create an environment where people can do their best to reach a common goal and deliver value to the customer.

The biggest gains for us stem from everybody involved in the harvest understands who the customer is and what they want. Lean makes us ready and flexible to adapt to changes in customer demand.

This is the harvest of the future – where competitive advantage is not to be found in machines, but in people. It’s all well and good to have modern equipment, but it is more important to have people who understand how to operate and how to use it to provide the best value to the customer.

JDR: What are your next steps?

LGA: We completed our pilot project in June. We are now going to bring lean to other areas and continue to run experiments. We want to engage support functions and suppliers, too. We wouldn’t want to have to slow our transformation down because they are not working like us!

Lean Institute Colombia is supporting Manuelita in its project “The harvest of the future”.

THE INTERVIEWEE

THE INTERVIEWER

Read more

VIDEO - The author of Lean with Lean explains why he published a collection of papers rather than a business novel - his signature writing style - or a manual. Experience lean through the eyes of one of its greatest students... one a-ha moment at a time.

NOTES FROM THE VIRTUAL GEMBA – Despite a 40% drop in sales and the looming prospect of having to furlough part of its staff, this French company is finding in lean manufacturing an ally to fight the current crisis.

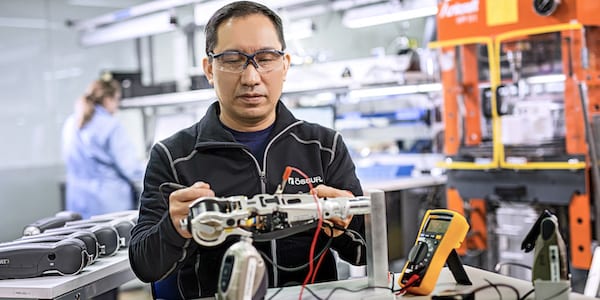

CASE STUDY - Össur is recognized as a leader in the fields of prosthetic, osteoarthritis and injury solutions, but how did lean management and a trial-and-error approach to improvement help it to stay competitive?

FEATURE – The authors discuss some of the most common problems that product development teams experience and what an effective assessment tool for engineering looks like.