Improve your lean coaching practice by acting with humility

FEATURE – Coaching people is the only way to truly develop their capabilities, but what does it take to become a good lean coach? Josh Howell on how humility helped him to improve his ability to coach.

Words: Joshua Howell, Senior Coach, Lean Enterprise Institute

"You've learned so much! You possess good thinking, more than before, that's for sure. You can break down and understand a wide range of situations, clearly define problems to solve, and know and can apply a variety of effective techniques to make things better. You can even teach others these techniques, people at all levels."

I remind myself of these things on the regular. Being a coach can be a lonely gig where the feedback loop can be long, or worse, absent. In spite of believing these self-"truths" and there being some supporting evidence, it does not guarantee that anyone else agrees. So it's important for me to continuously consider why someone might want to work with me, much less learn from me.

I've been doing this for a while now, practicing lean that is. It began in 2008 while managing a Starbucks cafe in Portland, Oregon. Not the typical beginning of a lean journey. It continued for about five years at the Starbucks headquarters in Seattle, Washington as part of a "lean team." And for the last two and a half years as Senior Coach at the Lean Enterprise Institute.

Of all that I've learned, a most useful lesson for my current practice involves humility. I see it demonstrated by the remarkable teachers I've had along the way. For one thing these teachers never refer to themselves as sensei, even though they include names like John Shook and Jim Womack.

BEING A HUMBLE COACH

This learning informs how I approach new situations, and people. I'd like to share that approach with you and I'll try below. For the purpose of illustration let's say I'm entering the deli of a supermarket.

In case you don't know, a deli is where you'll see bulk meat and cheese on display, available to be sliced to a certain thickness and to a specific weight. You might find hot, prepared foods like rotisserie or fried chicken along with various sides like mashed potatoes. You can find sandwiches if you're lucky.

Now let's say that I am coaching the people working in such a deli. In the past I would have entered the place with an air of confidence bordering on cockiness. I'd say hi the manager and team members. I'd size up the place by observing from the customer and worker perspective. Quickly, then, I'd start thinking or explaining to others how to proceed.

The certainty with which I'd articulate this "plan" would be well received in some cases. In others, most others in fact, it'd be met with scepticism, which could easily turn into active, or worse, passive resistance.

Take a recent encounter I had with a restaurant manager who had been asked to attend a meeting with me, the "lean guy." After exchanging little more than a greeting and our names, he said, "I'm curious. How hard is it to transfer manufacturing ideas into restaurants?" He was signaling his skepticism. And I hadn't done more than be the "lean guy." He wasn't interested in the least about what I had accomplished at Starbucks. To him I represented change. And he wasn't very interested in changing.

Ignoring the meaning behind his signals, I replied, "Ask me how hard it is to transfer ideas from one manufacturing plant to another manufacturing plant. It's hard! So it's definitely hard to take into a restaurant. Does that mean we shouldn't try?"

See, I can be a real jerk, a real know-it-all. My remark wasn't helpful. Fortunately I came to recognize that I'd pushed him away. So I changed course and quickly began a process of rework, one based on humility.

More mindful, I said the intent for our time together was simply for me to share with him some ideas and techniques that my teachers have shared with me. These have proven to be useful to me in a variety of situations. None of which have been in manufacturing, whatever that might mean. And since I'm sure he's struggling in some areas, because we all are, maybe these things will be useful to him as well. Change, if any is to come, will be his to create.

This approach resulted in a good day of learning.

HOW THE PROCESS UNFOLDS

Let's return to the deli and explore this approach a bit deeper. For starters, now I prioritize investing time really getting to know the team, especially management. I get to know how they feel about their work. I explore what they're proud of and what results they're known for. I pay respect to these achievements even if I see room for improvement.

Eventually they'll start sharing what they're struggling with. This is preferred to me pointing things out. It's good to remember that struggle always exists. The question is how to reveal it.

A quick aside. I've found a particular word choice to be helpful. I use the word "struggle" for issues workers are experiencing. Customer issues I refer to as "problems." This distinction helps people discern what is being worked on at any given moment. It can also signal to workers that struggles are important.

What I've noticed is that folks on the front line, doing the value-creating work, are actually visited quite often. This is contrary to the standard lean complaint that leaders never go to the gemba. This can also be the case of course. But rarely do these visits from leaders, and "others," involve being helped directly, much less immediately. So as these struggles are shared with me, I take direct and helpful action whenever possible. Are they struggling with how their backroom is disorganized? Ok, let's try organizing it. Are they frustrated that a particular tool always comes up missing? Alright, we can try to prevent that from happening.

Being helpful in this way, by addressing their struggles, may take some time. It may even take a few visits. The desired outcome here is for them to experience and gain trust in my intentions. Not just to hear about them. I want the help received from me to be different. Upon meeting this objective I might garner their permission to work on things they don't currently perceive as struggles, but that I've observed are problems their customers are experiencing, and to do so in a way that is likely new to them.

All the while, I am grasping the current situation. Starting with observing from the customers' perspective: What do they come here for? Is it easy to get what they want? Is the quality acceptable?

Then watching the work: What jobs are being performed often and repeatedly? How much of these jobs is value-creating, transforming a product or service closer to what will be paid for, versus wasteful motion?

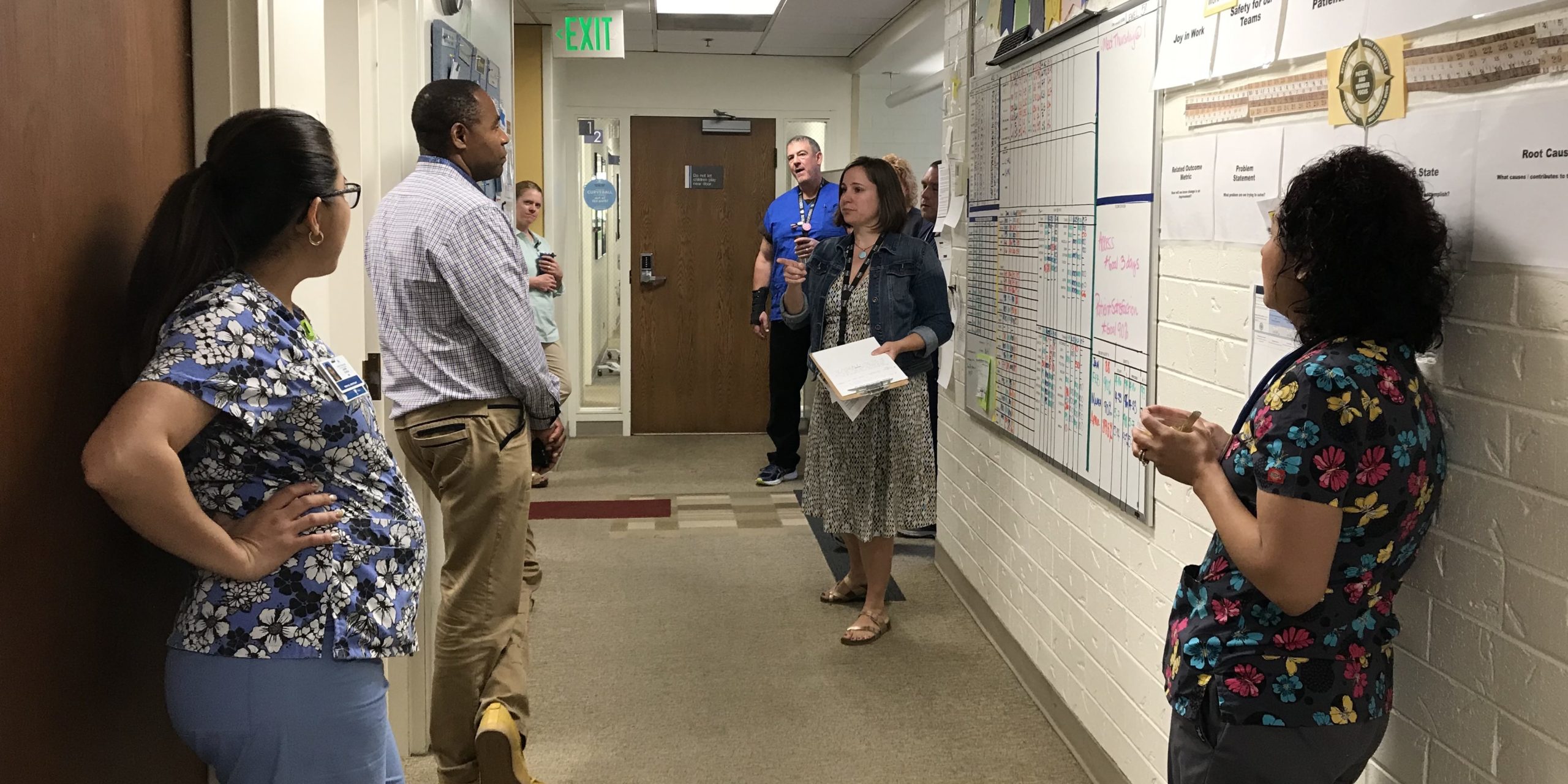

Next I'll look for signs of improvement or problem solving: Is there a clear plan for the day, for the work to be done? Is it visible when someone is ahead or behind? Are abnormal conditions visible from normal ones? What happens when an obstacle is encountered?

Lastly I'll observe management: How do they spend their time? Do they monitor performance in any way? How do they interact with team members and to what purpose?

You may notice that these questions flow from the Lean Transformation Framework:

PUSH OR PULL?

These observations give me a sense of the unique situation. Experience shows me that every situation is unique, from the team members to the managers to the customers to the layout. This is even true between two supermarket delis within the same company! More specifically I will have identified a key problem to solve, or two, or three. Problems that will benefit customers, primarily, but also team members and the business. I find that prioritizing benefit in that order – customers-team members-business – is highly effective.

Since I've established a positive and trusting relationship with the team members, supervisors and managers, I'm in a position to suggest working on specific problems based on my observations from the customer perspective. Maintaining the stance of being helpful is important here and so I'll lead solving the first problem. This also serves the purpose of allowing me to demonstrate the capability developed in me by my teachers, establishing credibility. Again, while I may have self-confidence in the statements that began this article, these folks in the deli haven't seen anything yet. They may appreciate my help, but are they willing to learn from me? Maybe yes. Likely no.

For this step in the process (and yes, it is a process) it's important to demonstrate high-quality problem solving. That is to say not only should the ultimate countermeasures work well, but the entire method (6 steps, 8 steps, 9...whatever) should be followed closely and made explicit. I look to Job Instruction's "Present" step in the four-step training process for inspiration here. Job Instruction compels the trainer to show the skill being trained perfectly. This demonstration will leave an impression with the trainee. It's important to make it a good one.

As we learn with problem solving, getting to the root cause so it can be eliminated, often requires countermeasures quite different than what we initially came up with. And when we combine brainstorming countermeasures with lean techniques, which are often unfamiliar and counterintuitive to folks, the result(s) can be quite impressive. Building upon the goodwill created when I rolled up my shirtsleeve, being not only helpful but highly capable sets up the situation, finally, for real transformation to take place. The team members and managers are now much more willing to go all in. And they're now open to learning... from me.

The process continues – content for another article. The key difference is push vs. pull. I've pushed lean on too many situations, and even more people. If pull from team members and team leaders isn't created (yes, I believe it can be created) then I'm wasting my time. Or it will take me much, much longer to achieve the conditions of transformation described above – trust, understanding of the current situation, collaboration, and willingness (eagerness?) to learn a new way.

You might ask yourself, are you pushing "lean" or creating pull for learning?

THE AUTHOR

Joshua Howell is a Senior Coach at Lean Enterprise Institute. Josh joined LEI after a decade at Starbucks, where he contributed to a lean transformation within retail store operations and management. Through interactions on the front lines up to the executive level, he understands the challenges individuals encounter when seeking to transform an organization, and more importantly, themselves.

Read more

CASE STUDY – A physician tells PL the story of how the East Denver Medical Office became a catalyst for the lean transformation at Colorado Permanente Medical Group.

FEATURE – A local branch of Italy’s Democratic Party has started using lean principles and tools to organize its activities more effectively and to counteract the discouragement that followed a bad electoral defeat.

CASE STUDY – Italian company El.Co. leveraged digitalization to overcome some key limitations of its manual kanban system while maintaining its pull system intact.

INTERVIEW – Overburdened and worn out? Visualizing your tasks using Personal Kanban can help you make sense of a busy schedule and reduce your stress, says Jim Benson.