Every lean implementation is different

INTERVIEW - Eric Ethington shares what he has learned about lean thinking implementations during his 30-year career holding positions at General Motors, Delphi and Textron.

Interviewee: Eric Ethington, LEI faculty member and founder of Lean Shift Consulting

Planet Lean: When did you first encounter lean thinking?

Eric Ethington: The program I was on at the General Motors Institute (now Kettering University) alternated between 12 weeks of classroom activity and 12 weeks of work at a sponsor company. From day one I was involved in experiential learning as an industrial engineer.

In that sense, to get into lean was not a stretch, even though at the time (the 1980s) industrial engineering did not have a focus on customer value.

After graduation I worked as an industrial engineer for GM in a lot of different functions. In the late ‘80s Japan was starting to make significant inroads in manufacturing in the United States, which created a big just-it-time push. But there was still no sign of customer value in the way we worked.

It wasn’t until the early ‘90s that lean “as we know it” started to come to light. At that point, I had moved to Delphi.

PL: Tell us about your career there, please

EE: I had a number of jobs within Delphi, running operations and doing a lot of capacity and market/product planning. At one point I was appointed DMS (Delphi Manufacturing System) Manager for the 5,000-people East Flint site. In the role I eventually took over the industrial engineering organization, trying to connect it to our DMS efforts.

In 2001 I went to Corporate to take on responsibility for DMS globally. My team and I put together the Lean Enterprise College, a week-long bootcamp-like learning experience for managers. We would take 18-20 executives through it, to give them a good base in lean and start to establish the leadership characteristics we needed.

Four years later, I went back to the steering division to work on establishing a robust launch process in all of our plants around the world. What we found is that while we had very detailed process and engineering development activity, there was still a gap between the engineering process design and a running and reliable value stream in the plant. We wanted to build a process that would bridge that gap.

PL: What were the most valuable lessons you learned while at Delphi?

EE: Definitely the things I learned from my mentor Yoshinobu Yamada, who had been General Manager of Production Control at NUMMI. The most important lesson is perhaps that it is critical not to confuse tools with goals.

Yamada’s answer to any question would be, “It depends.” This was another key takeaway, because it always brought us back to the thinking and to understanding the elements of the work to be done. Organizations often don’t get it, and base their problem solving on an incomplete idea.

PL: You then moved to Textron, which had been implementing six sigma. What did you find there?

EE: Six sigma has not given the company the traction they had hoped for, in terms of savings. The benefits were there, but not what the business needed. They called in several lean experts who could help them out. I was one of those brought in.

What I found was a strong focus on being certified. The process of accreditation has several criteria that must be met (a certain number of completed projects, a certain number of people coached, and so on), and a lot of projects seemed to have the purpose of getting people certified more quickly. This could potentially drive the wrong behaviors.

There was something else (although I see this happening a lot in lean too): the checklist approach. In the mid-90s at Delphi lean was a lot about tools and checklists, but what we evolved to understand was that every situation has a different current state (for example, injection molding in one facility is different from injection molding in another) and therefore requires a different approach. In six sigma the checklist approach observed: you go through gated steps and this almost hurts learning. The assumption is that when you go from one gate to the next you do so with almost perfect knowledge.

Very often, six sigma’s approach does not account for PDCA. I do not mean that it can’t, but it is often not practiced that way. So long as we are trying to understand something, it doesn’t matter what tools we use because, ultimately, there is no such thing as perfect understanding. Situations change, we learn new things, and we adjust our approach.

PL: When you were heading corporate lean for Delphi, you learned that every implementation is different. How did you match that with the need to have a consistent strategy in place for the entire organization?

EE: That is always the struggle. What we tried to do was to standardize the thinking as much as possible.

There are times when you can do it, when the current states are very similar for example. At an assembly plant we worked in, 10 of the 13 lines were pretty similar: we picked one and came up with a concept for it in four months, after which we were able to change a line every week.

But in general we came to realize that lean is rarely “copy and paste.”

Think about an injection molding operation in two plants. In one you have Automated Guided Vehicles picking up completed parts, and in another you are making a bunch of small parts for a number of areas. You cannot come up with one image for injection molding in such a scenario, unless you want to set yourself up to fail. There are different current states and situations, and in the same way there should be different future states, too.

We can easily fool ourselves into thinking that we can take an approach and blindly apply it everywhere else, but we rarely get the expected results from doing this.

PL: You also have experience with hoshin kanri. What is the most common misconception that people have about it?

EE: Many seem to believe that so long as they have a strategy people are automatically going to understand what they need to do down the organization. You can have a few key high-level strategic objectives and communicate them throughout the business, but if you don’t explain what those mean to each level the entire exercise is useless. What is the action I need to carry out to contribute to this strategic goal?

To be fair, the same happens with goal deployment. We often don’t take the time at each level to look at a problem logically, break it down to understand what actions it translates into for the folks working for us. If I am a supervisor, a general budget target means less to my team than scrap and daily productivity targets.

PL: You define hoshin and A3 as skeleton and muscles respectively. Could you expand on this, please?

EE: Hoshin is the framework that allows you to figure out the process to communicate objectives: we are going to have these goals at organizational level, these are the related responsibilities, and these are the concrete actions that will contribute to the achievement of the goals.

To understand what these actions are, we need to work with A3s.

How you pick an objective and cascade it is the skeleton (hoshin), while the muscle is going through problem solving and coming up with countermeasures for the root causes (A3).

THE INTERVIEWEE

Read more

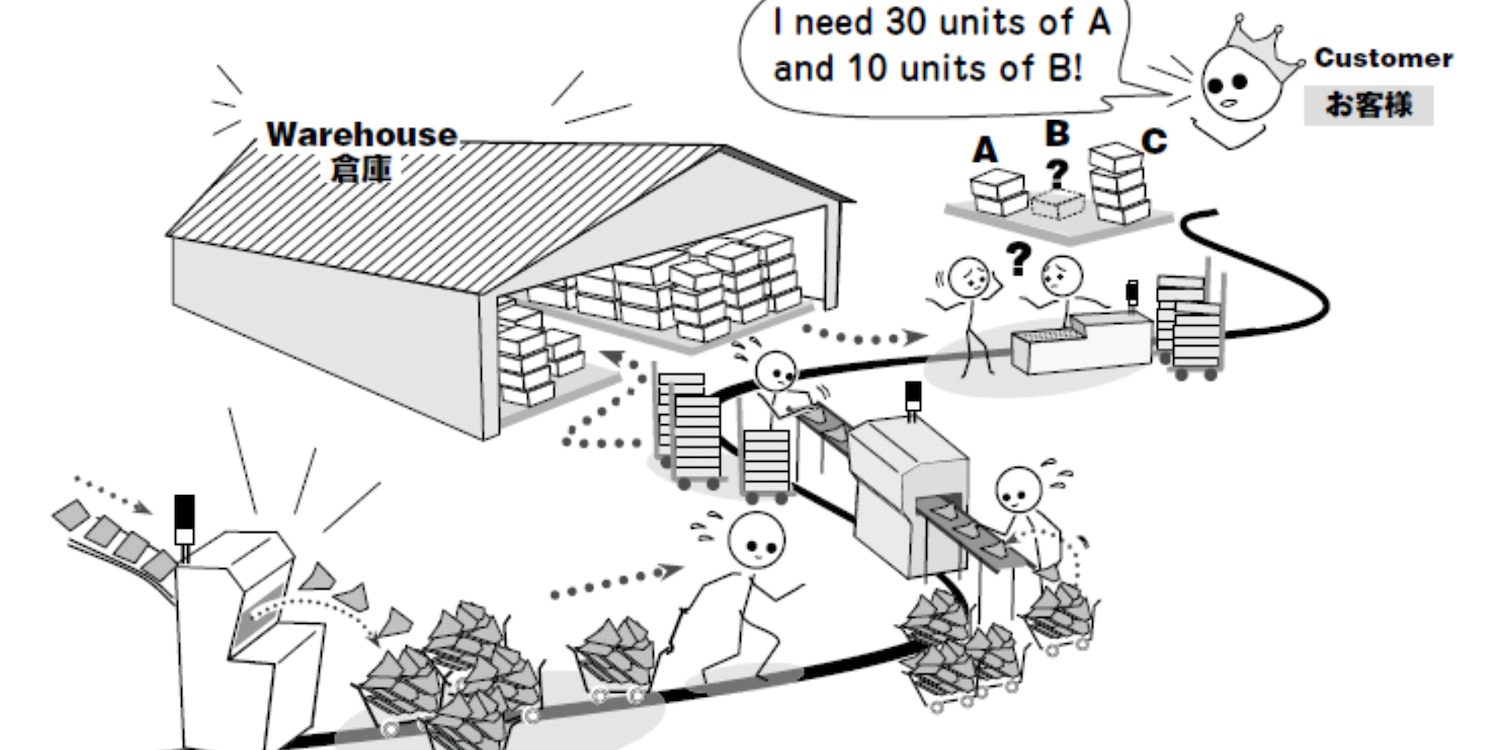

FEATURE – The release of Christoph Roser’s new book All About Pull inspires John Shook to discuss the origins and true meaning of “pull” and why it is incorrect to blame JIT for the shortcomings of global supply chains.

FEATURE – Why is lean change so hard to achieve in times of plenty? And why does it seem to be more attainable when chaos reigns? The author tries to answer these questions.

CASE STUDY – What to do when you operate in a competitive market and are located in a remote corner of Europe, thousands of miles from your customer? One word: lean.

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – What does a lean employer look like? In this month’s column, the author reflects on the long-term commitment to employees a company engaged in lean thinking should make.