Drew Locher: why lean thinking and leadership are one

INTERVIEW – Planet Lean talks with Drew Locher about bringing change to an office setting, lean in small- and medium-sized firms and why improving and managing go hand in hand.

Interview with: Drew Locher, President, Change Management Associates

Roberto Priolo: You first adopted lean principles and practices while at GE in the 1980s – what did that experience teach you?

Drew Locher: I participated in one of GE’s Corporate Management Development Programs and we were consistently given “lean” notions – the term “lean” hadn’t been coined yet – as we were taught to lead and manage. From the very beginning, I was told that lean is an integral part of how you lead.

As the years went by (I left GE in 1990), however, I found that this is not so common and that managing and improving are generally viewed as separate actions. Instead, we need to get leaders to accept that running a business and improving a business are equally important parts of their job.

I was taught early on that these two things are interconnected, that continuous improvement doesn’t only happen part-time.

RP: We are used to seeing lean in action in large organizations, even though the economy of many of our countries are predominantly made of small- and medium-sized organizations. What’s the main challenge for smaller firms that want to adopt lean?

DL: My early customers after I left GE were all small- and medium-sized manufacturers. I worked with job shops at the time, and that was a fantastic experience for me, which taught me how to adapt lean concepts to the circumstances of that type of organization (although, to be honest, I had learned quite a bit about that in GE already, because I used to work in aerospace, which is certainly not a high-volume environment).

The people I worked with back then were like sponges and just wanted to learn more and more. They were not just entrepreneurs; they really led by example and lived at the gemba.

In small organizations you can’t delegate the work to a kaizen team, you have to be a part of it. Improvement has to become embedded in what you do. You just can’t separate work and improvement.

In many ways I think it’s easier to bring lean to an organization that is small – you have fewer people to convince, right? However, the difficult part is getting the owner to give more and more responsibility and authority to the people he or she puts in place as the company grows. That requires a lot of coaching.

RP: Can you share a few tips on what to look out for when introducing lean in an office setting?

DL: I believe that you must adapt your stance to every new environment you work in. Forcing language and concepts you have learned in one environment onto people working in another environment doesn’t cut it (which is one of the biggest issues I have seen with people who have left manufacturing to facilitate lean transformations in office environments), because the nature of the work is different. The good news is that it still screams for the need of lean management: lack of standardization and high levels of variability, for example, are problems lean can help us to tackle.

While pull and flow might prove a bit difficult to apply “as they are,” the general problem solving and process improvement methodologies, like A3s, don’t present particular problems and translate easily.

RP: At this year’s Lean Management Conference in Wroclaw, Poland you are going to talk about the application of lean to knowledge work. What’s the best way to approach knowledge workers in the scope of our lean transformations?

DL: Again, you need a bit of a different approach. First of all, you must respect where people are coming from in terms of knowledge and skills: in my experience, the key is to get people to talk about their problems. We all face problems, and getting people to talk about them is how I normally manage to connect with them – whether or not they are knowledge workers.

When you start to talk about things like standard work, they normally start pushing back, saying “everything is different.” The biggest thing with knowledge workers is getting them to see process, convincing them that what they do has a process, regardless of what the final product is. People often get hung up on the output, but it’s the process they should be focusing on. When you start mapping the process of designing two completely different products, for example, people quickly realize it doesn’t really change that much.

RP: In Poland, you will also talk about lean development of products and services. What role do approaches like 3P design have to play?

DL: PDCA is a learning cycle, so any approach that can lead to quicker learning cycles – like rapid prototyping – is important to understand and adopt. It’s critical to know sooner rather than later if what we are designing is going to work or not. We learn more by doing than we do by talking, so instead of getting the layout just perfect on paper we should choose to just get on with it and experiment.

3P design is based on these ideas, and it greatly helps with the creative process. It does so in a number of ways, including rapid prototyping, bio-mimicry and the 7 ways. The latter has become particularly popular in some hospitals, which have really latched on to it and have made it part of their every-day language. When considering countermeasures they identify seven possible ways before narrowing to one, which is usually a combination of ideas. So 3P can apply to services.

3P applied to product (or service) and process development really stretches our thinking and what comes out of that are very creative ideas.

THE INTERVIEWEE

Read more

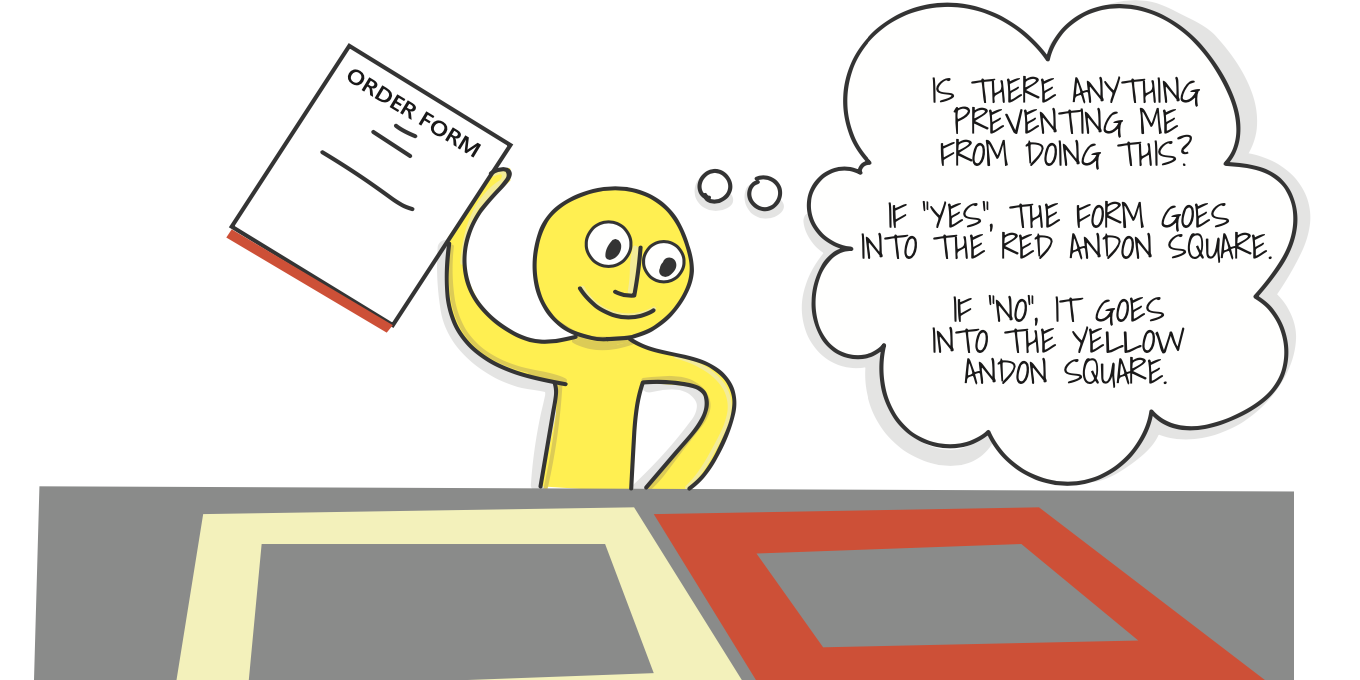

FEATURE – As she gets ready to publish a book on her experience running Halfway Toyota Ngami, the author looks back at one of the best visuals the team implemented during the transformation.

FEATURE – Sometimes all you need to change minds is a successful experiment. This is how a Norwegian furniture manufacturer managed to transform the way it thinks about its sofa production.

RESEARCH – Why do we struggle to identify the managerial behaviors that underpin different stages of a lean transformation? The author’s research looks into how we can be more situational in our leadership approach.

FEATURE – In this intimate account, the author reflects on the role of a lean sensei by looking back at what he’s learned from his own… his father.